In today’s hyperconnected world, a single glitch can ripple across continents — turning a minor hiccup into a global disruption.

According to Ariel Pinto, professor and chair of the Cybersecurity Department at the University at Albany’s College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity, understanding these cascading risks is essential to protecting the systems we rely on daily, from hospital equipment to the power grid.

Pinto believes that learning from past failures, focusing on the human element and taking a forward-looking approach can help the next generation of cybersecurity professionals protect our cyber systems. This begins with a shift in how we define, communicate and act on cyber risk.

What Cyber Risk Really Means

Effectively managing cyber risk begins with understanding what cyber risk actually is — and what it isn’t.

“Cyber risk is when our cybersecurity infrastructure fails,” explains Pinto. “Cyber [technology] is built into almost everything we do nowadays. When everything is working as designed, no problem. But when cyber technology starts failing, that’s where risk comes into play.”

Risk doesn’t just stem from hacking, malware or catastrophic breaches; it also involves the potential failure of the cyber infrastructure that underpins nearly every aspect of modern life.

From smartphones and online banking to connected cars and smart thermostats, our daily routines depend on these systems functioning flawlessly. The true test of cyber risk management comes when these systems falter, revealing vulnerabilities that often stem not from sophisticated attacks but from human error, oversight or omission.

Recognizing that the human element remains one of the most significant risk factors is the first step toward building a stronger, more resilient digital environment.

Lessons From Past Failures and the Role of a Cyber Risk Custodian

One of the clearest lessons in cyber risk management, according to Pinto, is how small failures can escalate into major crises when systems are interconnected. “Imagine the domino pieces getting bigger and bigger as they fall,” explains Pinto, noting that a seemingly minor disruption — such as when a small company’s infrastructure failure causes a service outage — can ripple outward to impact clients, partners and entire industries.

He likens it to a fender bender on the highway: The incident itself may be minor, but the resulting traffic jam can stretch for miles.

This understanding of cascading failures shapes Pinto’s role as what he calls a “custodian of cyber risk.” Pinto has conducted numerous studies on risk, writing journal articles, writing textbooks and making presentations on the subject for academics and industry practitioners alike. Much like a historian or librarian, he collects and studies stories of past system failures, not to dwell on mistakes but to extract insights that can help anticipate and prevent future ones.

The 2003 Northeast blackout is one example he revisits often. While it was triggered by something as simple as a tree branch touching a power line, the blackout halted transportation, cut off water supplies and plunged millions into darkness. In his research work, Pinto asks: What if that same chain reaction began today with a cyber-related failure, such as a software bug?

By examining these scenarios, Pinto and his fellow researchers can model potential outcomes in today’s more resilient but still highly interconnected digital environment. The goal is to equip organizations — and the students he’s training to protect them — with the foresight to identify vulnerabilities before they spiral into large-scale disruption.

Communicating Risk and Preparing for the Inevitable

For Pinto, one of the greatest challenges in cyber risk management is convincing organizations to prepare for events they may never experience firsthand. Unlike a single corporate network or a municipal water system, there’s no central authority overseeing the global cyber infrastructure. “No one owns it, but everyone gets affected by it,” he says, likening the issue to environmental pollution: The actions, or inactions, of one entity can have consequences for many others.

That interconnectedness means a business can invest heavily in securing its own systems, yet still be compromised if a partner, vendor or neighbor fails to do the same. Pinto encourages leaders to start by quantifying potential losses — not just for their own operations but for society at large — so they can justify cybersecurity investments to stakeholders. Without that clear sense of what’s at stake, it’s all too easy to justify underinvesting until it’s too late.

His analogy is simple but effective: “It’s like having your spare tire in your car. Not everyone has a flat tire, but everyone needs to know where their spare tire is and how to use it.” The same logic applies to cybersecurity. Even if an incident never happens, organizations need a plan B — from backup systems to incident response protocols — ready to deploy at a moment’s notice. Because in Pinto’s view, the worst time to figure out your response to a cyber incident is while you’re already in the middle of one.

Bridging Academia and Industry for the Next Generation of Cybersecurity Leaders

Emerging threats such as artificial intelligence-generated phishing emails and deepfake visuals make it harder than ever for individuals to distinguish legitimate content from malicious fabrications. Pinto sees this as a turning point, where cyber risk management must evolve from a purely technical discipline into a “sociotechnical” one that accounts for economic, political and human factors.

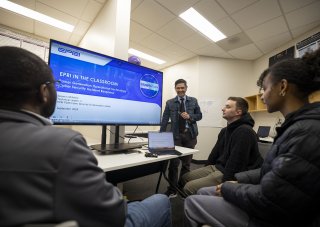

That’s why the University at Albany’s Bachelor of Science (BS) in Cybersecurity program drills students early on to think critically, spot interdependencies and adapt to a landscape where technology changes faster than any single curriculum can keep pace.

“We don’t just impart knowledge, we impart experience,” explains Pinto. This means bringing industry into the classroom, partnering with sectors such as power generation, finance, and healthcare to ensure that students graduate not only as cybersecurity specialists but also as versatile professionals who understand cybersecurity as an essential layer in every career path.

Discover Your Potential in Cybersecurity

In addition to Professor and Department Chair Ariel Pinto, the interdisciplinary faculty of University at Albany’s cybersecurity bachelor’s degree program includes lawyers, engineers and computer scientists, broadening students’ perspectives while introducing them to new areas of exploration, such as cybersecurity in the gaming industry.

The need for skilled, adaptable cybersecurity professionals has never been greater. The threats are evolving, the stakes are rising and the next generation of leaders will need to combine technical expertise with critical thinking to keep our digital infrastructure resilient.

If you’re ready to be part of that solution, explore UAlbany’s online or on-campus BS in Cybersecurity program and start building the skills that can protect the systems our world depends on.

Showcase 2025: CEHC Students Study Real World Impact of Cyber Attacks

Capstone Course Trains Students for Cyber Threats in the Financial Industry

5 Questions with CEHC Cybersecurity Chair Ariel Pinto