Solving Biotech Pain Points with RNA Switches: Q&A with Doctoral Student Tia Swenty

By Erin Frick

ALBANY, N.Y. (Oct. 30, 2025) — Doctoral student Tia Swenty came to the University at Albany with a keen interest in biochemistry and sharp sense of what it takes to transform bench research into something people can use.

Fueled by her participation in the NSF I-Corps program, part of the Research and Innovators Startup Exchange (RISE) program administered by UAlbany’s Department of Economic Development, Entrepreneurship and Industry Partnerships, Swenty had the opportunity to work with a carefully matched team of students to learn what it takes to translate findings made in the lab to market. Guided by this experience and working with this team, she took to the art of customer discovery and conceived of a way to answer one of biotechnology’s most pressing problems using the platform technology at the center of her research.

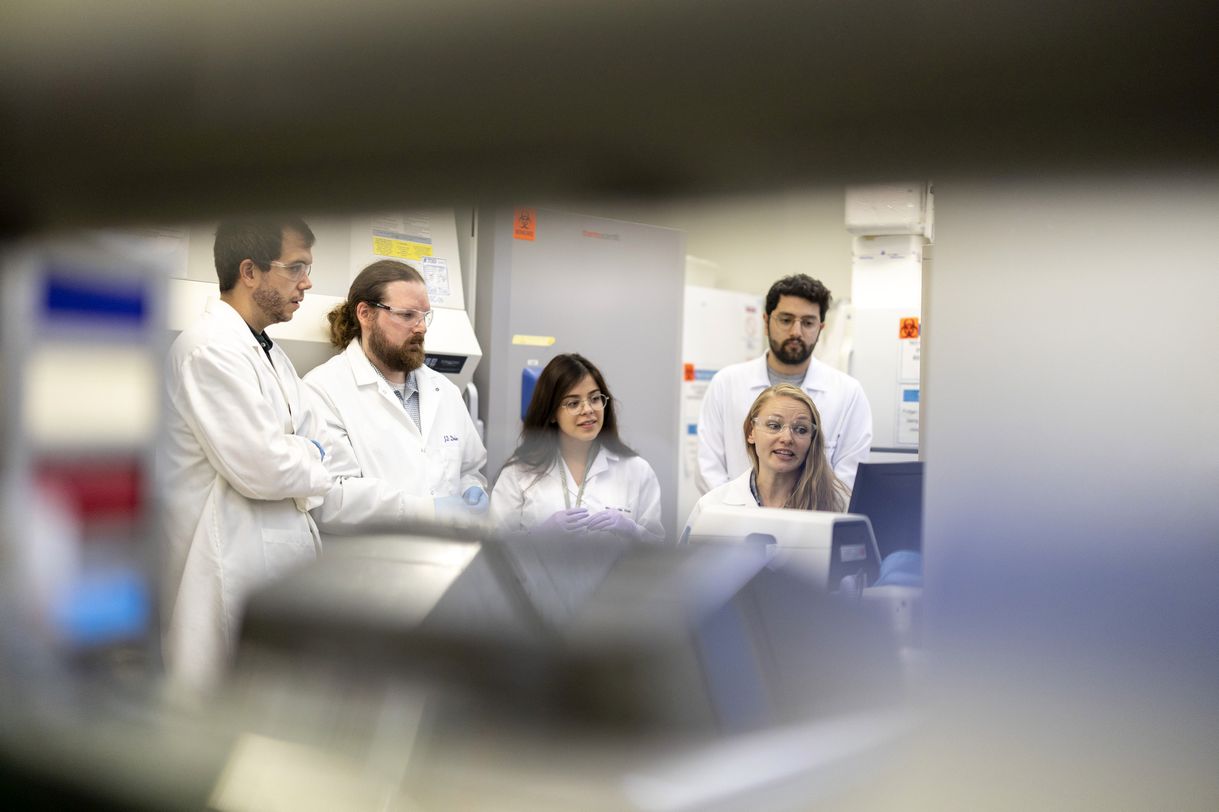

Swenty is a third-year doctoral student working in the lab of Professor Scott Tenenbaum at the College of Nanotechnology, Science, and Engineering. She is supported by several competitive funding streams including a fellowship from UAlbany’s RNA Institute and an Institutional National Research Service Award granted by the National Institutes of Health.

We caught up with Swenty to learn about her interest in nanobiotechnology and RNA science, what sort of problems she is currently working to solve, and how thoughtful market research can inform the pursuit of science for real-world impact.

When did you become interested in RNA science?

It all started during my undergraduate studies at Arizona State University. I was really interested in genetics — how our DNA works and how it shapes how every person becomes who they are. One class in particular, “RNA World,” opened my eyes to the complexity of RNA. It's not just the code that translates your DNA into the proteins which make your cells work; RNA has its own behaviors, its own mysteries, and performs a wide variety of functions in our cells that aren’t fully understood.

This sparked my interest — for something so important, why don't we know or understand more about it? And it's not that scientists aren't trying; it's that we're still developing the technology needed to fully study its complexity. This is part of what my work aims to address.

What drew you to UAlbany?

When I was looking for graduate programs, one thing that really caught my attention was Professor Tenenbaum’s work on “structurally interacting RNA” (sxRNA). Because I was interested in RNA biochemistry, I knew that was exactly the type of thing I wanted to study.

When I interviewed here, I felt very at home. I was invited to the annual RNA symposium so I could see the work they were doing at the RNA Institute. Even though I wasn't a UAlbany student yet, I felt immediately integrated. It felt like the right place for me.

What is ‘sxRNA,' in simple terms?

At the very basic level, sxRNA, which stands for structurally interacting RNA, is a molecular switch that we can control. Like a light switch, it can turn cell processes on and off. The system is comprised of two pieces of RNA. One piece — the RNA that we make in a test tube in the lab — has a flexible structure that starts in the “off” position. It will only turn “on” when it meets a specific cellular target.

Your cells make different types of RNAs in each cell type — your skin makes different RNA compared to your heart or liver. We design our RNA nano switches to bind to one of those RNAs made in one of your tissues. When the two pieces of RNA come together, the one we designed then activates. Because our RNA switches are cell-specific, they have lots of potential uses, including in medications.

For example: if you look at cancer therapy that goes throughout your entire system — we call that systemic treatment — it affects all cells and causes side effects. But if we put our sxRNA switch into a medication like that, we could make it target only a specific cell type or tissue. We could program it to destroy tumor cells without harming healthy cells.

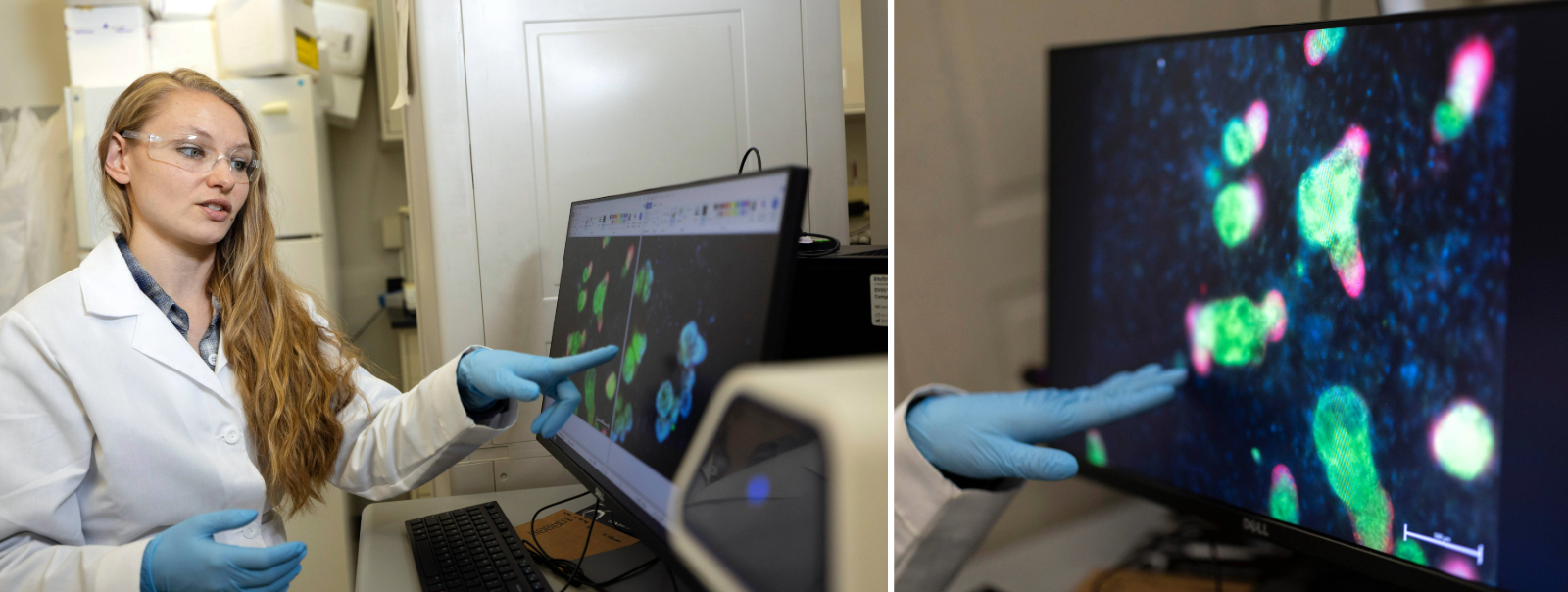

We can also use sxRNA for diagnostics to test for different RNAs in your system; as a tool to activate fluorescence in different cell types so we can see what cells are there; and in biomanufacturing, where we can activate translation of a specific protein.

What problem are you currently working to solve?

Right now, I'm working specifically with organoids — very small, lab-grown representations of our different organs commonly used for research into understanding disease or developing new drugs. I'm using sxRNA to help show when stem cells make new cell types. This application could be used for testing pre-clinical pharmaceuticals.

The field of biotechnology is currently transitioning from animal models to more human-type models using organoids. A problem in this transition is that researchers using organoids need to destroy a portion of each organoid “batch” in order to check whether they are growing properly. They make huge batches and routinely sacrifice at least 10% to test during development, creating a lot of waste.

I'm working on designing our sxRNA so it can be used to monitor organoids non-destructively. Our sxRNA is transient — you can add it to an organoid, and a couple days later, it's no longer there. Using sxRNA, I can make certain cells within the organoids fluoresce a certain color, which tells you what you need to know about each individual organoid, without destroying any in the process.

This could have huge implications for research efficiency and cost savings. Some organoid cultures, like brain organoids, could take up to 100 days to develop and require regular inputs of expensive growth factors. By improving quality control procedures, we can help alleviate waste and excess costs.

How did you decide to explore this particular problem?

This research direction was born out of a customer discovery project as part of the Research and Innovators Startup Exchange (RISE) program. "Customer discovery" means going out and talking to people within a field about their problems and what they wish could be possible.

In this program, I was matched with a team that included undergrads, a business student and a law student. We targeted the organoid field and talked to 20 different people to learn about their pain points. This is how we learned about the ubiquity of waste in organoid research, which is part of what makes it so expensive.

It was exciting to listen to stakeholders’ problems and have that lightbulb moment when I realized that we have the tools to develop a solution to what is clearly a big problem in the biotech field. I presented my ideas at a 3D tissue summit, and people were very excited and said this technology would be extremely useful to their work — which was encouraging.

What do you enjoy most about your research?

I get to play around with new technologies that I've never used before. Plus, all the RNA nanoswitches I'm developing, I'm making and testing myself.

I’m also excited about the potential for success — that our tool will give researchers a non-destructive way to study living cellular systems. If our RNA switches work as I'm envisioning, it could change how scientists approach cell biology research, allowing them to observe, characterize and then continue experimenting with the same samples.

What advice would you give students trying to find their research direction?

I think it's really important to go out and see what other people are doing. Find somebody who has a problem and think if you can find a solution for it. I would have never thought to pursue this question unless I went out with a team and asked people about the challenges that they are facing in their work. Technology development is one of the most interesting things I could be working on for my PhD, so I'm excited to be making it happen.