Udo Lab Partners with Project Safe Point: Community-Engaged Research for Harm Reduction

— Video filmed and produced by Zach Durocher.

By Erin Frick

ALBANY, N.Y. (Jan. 28, 2026) — The University at Albany is dedicated to conducting research for real-world impact. This includes partnering with local organizations to align projects with community-driven needs.

Associate Professor Tomoko Udo’s partnership with Catholic Charities, one of the largest social services agencies in the greater Albany region, is a longstanding example of such a collaboration. The agency addresses basic needs such as providing food, clothing and shelter as well as more specialized resources like mental health counseling and services for substance use. One area of focus is helping reduce harm associated with drug use, work collectively referred to as “Project Safe Point.”

Udo, who is an associate professor in the Departments of Health Policy, Management and Behavior and Epidemiology & Biostatistics at UAlbany’s College of Integrated Health Sciences, started working with Catholic Charities' Project Safe Point in 2016.

“UAlbany is focused on research that helps the public good and working with community partners here in Albany is a really effective way for us to do that,” Udo said. “For about a decade, I have built a strong, mutually beneficial partnership with Catholic Charities' Project Safe Point, based on a common goal to improve health and quality of life for people who use drugs. Examples of our collaborative research projects include estimating prevalence of hepatitis C for the New York State Department of Health and a wraparound harm reduction service for those re-entering into the community after incarceration.

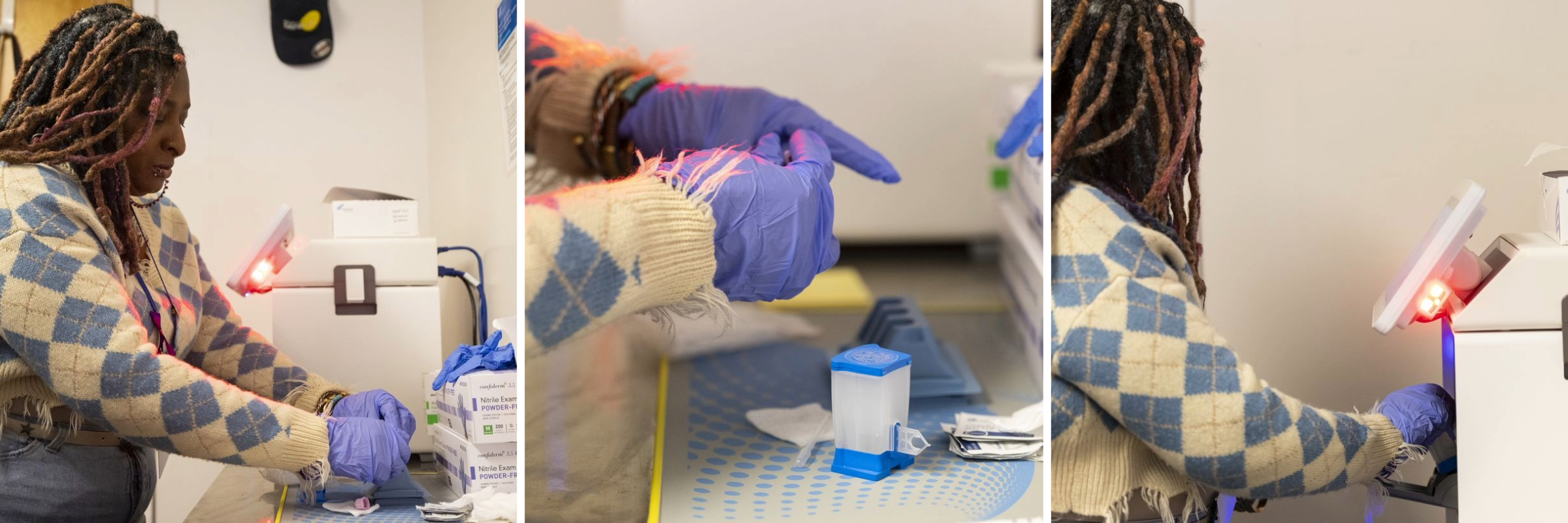

“Our most recent accomplishment was becoming part of a federally sponsored clinical trial to get a new point-of-care hepatitis C diagnostic machine approved by the FDA. By providing fast, reliable diagnostics, this is a much-needed tool to help eliminate this disease.”

Project Safe Point

Project Safe Point is a harm reduction program partially funded by the New York State Department of Health that provides essential health services to people who use drugs across a 12-county region in the Capital District. The program’s offerings are comprehensive, including syringe exchange, overdose prevention services, drug checking and clinical testing for diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C. When clients test positive, patient navigators help them access treatment, arrange transportation and ensure they receive appropriate medication. Beyond physical supplies and medical services, counseling is central to Project Safe Point, with its staff members trained to help clients reflect and consider recovery options.

“At its core, Project Safe Point takes a holistic, client-centered approach to supporting people who use drugs in recognition of the reality that not everyone is ready to stop using substances but can still benefit from services that reduce harm,” said Udo. “For some, these intermediary interventions can be an important bridge towards stopping use. And, when it comes to communicable disease, reducing disease prevalence within a population helps protect everyone.”

Partnering to Improve Care

Collaborations between UAlbany and Project Safe Point originate from both sides. When Project Safe Point staff identify programmatic needs, Udo's team can step in to provide evaluation support. Other times, researchers bring project opportunities to Project Safe Point, including ones initiated by partners like the State Department of Health.

Much of this work focuses on understudied populations, with a recent emphasis on people who smoke drugs — a group that is growing, partly due to perceptions that smoking carries lower disease risk compared to injection. Through qualitative interviews with Project Safe Point participants, researchers work to identify behavioral patterns and knowledge gaps around drug-related health risks.

Udo Lab member Zhi Chen, a PhD student studying epidemiology, is analyzing data from the Integrated Services for Infectious Disease Elimination (INSIDE) project, which partners with syringe exchange programs across New York State to guide hepatitis C elimination efforts.

“One reason why I really like public health and epidemiology in particular is because our results and findings can have direct implications for population-scale health intervention programs and public health policies,” said Chen. “UAlbany’s involvement in this kind of work, especially in collaboration with the New York State Department of Health, is why I decided to pursue my PhD here.

“For example, for the INSIDE project, we are using our data to inform Project Safe Point staff about the characteristics of the people who participate in their harm reduction programs. Something that I’m particularly interested in are differences in drug use and disease prevalence between sexes. Men tend to use drugs more than women, but this doesn’t mean that women are at a lower risk of diseases like hepatitis C. Our hope is that by underscoring this reality, we can help bring better care to women who have traditionally been neglected in public health policy and intervention programs aimed at hepatitis C elimination.”

Udo's team compiles information collected from Project Safe Point participants into site-specific reports for program locations across the Capital Region. Equipped with these analyses, which include data on participant characteristics, testing results and substance use patterns, Project Safe Point staff can better understand what supplies are needed, identify shifts in substance use, and refine their engagement strategies. Findings are also shared with policymakers to advocate for changes that could improve health outcomes for people who use drugs.

Community-Engaged Learning

The partnership also benefits UAlbany students by facilitating experiential learning opportunities that offer a firsthand view of the complete research cycle — from data collection to policy implications to health outcomes.

Undergraduate researcher Maxwell Gustin is among the Udo Lab members involved in Project Safe Point who has been able to see how his work can directly impact community members and programs.

“We're looking at behavioral patterns in substance use as well as treatment use and accessibility,” says Gustin, who’s majoring in human biology with a minor in medical anthropology. “We're asking participants questions that address things like history of substance use and how their use has changed over time. We then use that data to identify patterns and ultimately craft recommendations.

“Using this method, we have been able to identify knowledge gaps around hepatitis C risk. For example, many people know that you can contract hepatitis C through injection, but they don’t know that it may also be spread by smoking. This kind of revelation can make a tremendous difference in behavior that can help curb the spread of hepatitis C. This is critical for not only stopping disease among the people we work with directly; this level of protection also helps safeguard the broader community.”

Gustin sees his work with Project Safe Point as a union of several interests which together support his goal of one day becoming a physician.

“I love all of the things that I've been able to learn working in the Udo Lab," he said. “I have a traditional pre-med background that involves a lot of basic sciences, chemistry and biology. The Udo Lab is an intersection of these disciplines together with epidemiology, public health, sociology, psychology and other fields. Working in this lab has exposed me to a completely new research approach, which will make me a better physician in the future.

“In the Udo Lab, I feel like we're making a difference," Gustin said. "We're creating relationships and fostering bonds. And it's not a one-off interaction; it is a continuous domino effect that benefits everybody in the community.

“I understand that this work has critics who may advocate against giving out safer smoking supplies. But what the research has found is that by doing this, we're actually benefiting the community as a whole. It's not just the substance using population who is at risk. Infectious diseases are infectious and the only way that we can protect everyone is by stopping disease where it’s in our power to do so. This work is a great example of how caring for a traditionally marginalized group can have reverberating benefits for an entire community.”