RNA Institute Researchers Receive NIH Funding to Investigate Fatal Genetic Disorder

By Erin Frick

ALBANY, N.Y. (Sept. 25, 2025) — University at Albany scientists at the RNA Institute are seeking to understand the molecular mechanisms that drive disease. In Kaalak Reddy’s lab, they are studying a rare but fatal genetic disorder that affects the heart and brain. Known as ITPase enzyme deficiency, the disease is caused by a missing enzyme (ITPase) that is responsible for cleaning up unconventional nucleotides in cells. Without it, the coding instructions carried in RNA get disrupted, causing problems in heart and brain cells, leading to death.

A molecular material called inosine (I), which plays important roles throughout the body, can turn toxic when it accumulates unchecked. In this disorder, which is fatal in childhood, excess inosine accumulates in RNA and disrupts the ability to create essential proteins needed to support a healthy heart and brain.

“RNA molecules are made up of building blocks called nucleotides which typically include adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C) and uracil (U),” said Kaalak Reddy, research faculty at UAlbany’s RNA Institute who has been studying this disorder since 2014. “These building blocks provide the code to maintain RNA functions which includes generating proteins that keep cells functioning properly.

“Inosine (I) is another type of molecular building block, but it is not a common part of all RNA sequences. When too much inosine accumulates in cells, it can get incorporated into the RNA sequence, where it causes problems. Essentially, the cell isn’t used to reading I’s in the code, so it gets confused. As a result, critical systems in the body cannot function as they should.”

In most people, there is a mechanism that keeps all of this in check. Inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase enzyme (ITPase enzyme for short) eliminates extra inosine nucleotides. Even a small amount of this enzyme in the body will prevent the RNA code from getting clogged with erroneous “I” instructions.

“We are trying to determine why the accumulation and misincorporation of inosine into RNA leads to a fatal disease,” said Reddy. “This understanding could give us new insights into the cellular mechanism underlying this and other related diseases.”

The work was recently awarded $420,000 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. UAlbany Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Gabriele Fuchs is a co-lead investigator on this grant.

“Not much is known about the broader cellular consequences of this inosine misincorporation into RNA,” said Fuchs. “Our previous work shows that inosine misincorporation disrupts the process of making proteins and their function, which is a central question that my lab will address in this work.”

Spotting Typos in the RNA Code

To study inherited ITPase enzyme deficiency, the researchers are growing heart and brain cells using specially programmed stem cells that lack the ITPase enzyme. By reading RNA sequences extracted from these cells, they will be able to spot where inosine is disrupting the RNA code.

“We know that inosine buildup causes problems in this disorder, but in order to begin finding a treatment, we also need to know where the problem starts,” said Reddy. “This includes identifying the exact locations of the extra I’s within the RNA sequences.”

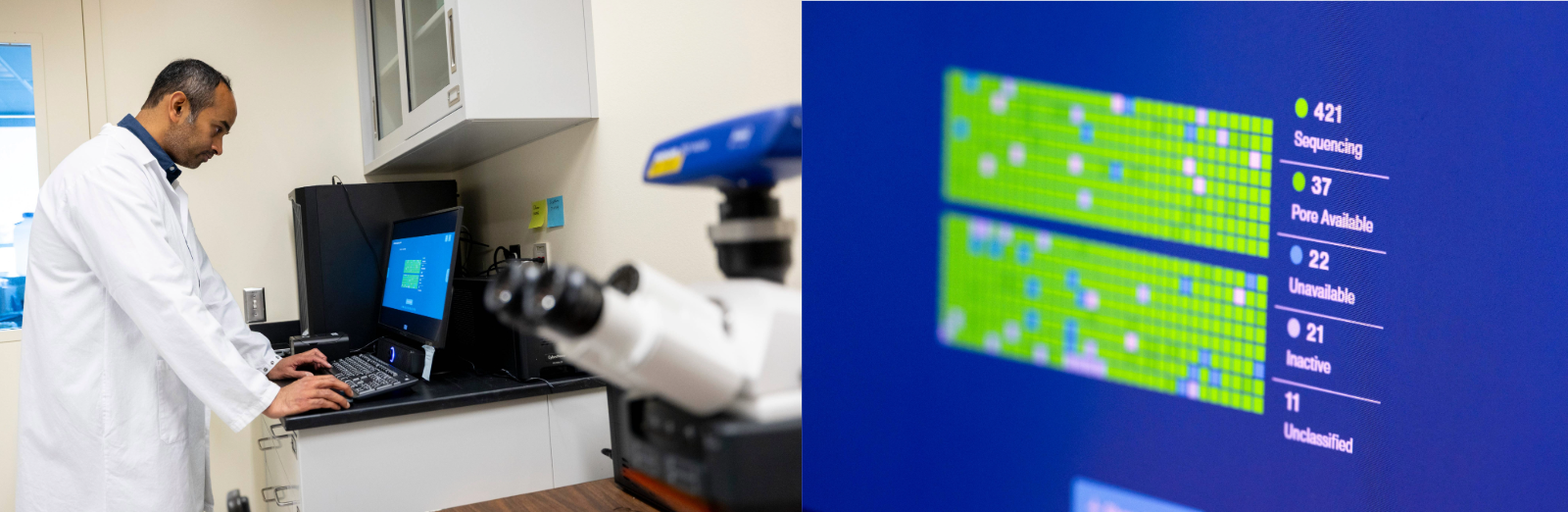

To see where inosine is being incorporated in RNA taken from affected heart and brain cells, the team is using an instrument called the PromethION sequencer from Oxford Nanopore Technologies. This device can directly read RNA sequences extracted from cell and tissue samples in real time. By running RNA strands through tiny, charged pores made of proteins, the device can detect a current signature unique to each nucleotide. This makes it possible to map where the problematic inosines may occur in the RNA sequence.

The PromethION nanopore sequencer is housed in the RNA Institute’s transcriptomics core — a suite of best-in-class instruments that not only enable researchers to directly sequence RNA, they also have tools for analyzing properties of individual cells and mapping the location of hundreds of RNAs within a tissue sample.

Expanding Understanding

“Identifying the location and consequences of the problematic I’s in the RNA code will help us understand the origin of this disease,” said Reddy. “From there, it becomes possible to start imagining what sort of therapeutics could help stop the problem at its source. While this particular disease is very rare, by better understanding its underlying cause, we can simultaneously gain understanding of cellular mechanisms that cause related disorders.”

Lessons learned in these pursuits can also support the development of unrelated therapeutics. For example, in the course of Reddy’s work, they discovered that mRNAs with high inosine accumulation can trigger a strong innate immune response.

“Across most scientific disciplines, learning what not to do can be just as important as learning what works,” Reddy said. “With mRNA containing high inosine concentrations, we see a strong immune response — essentially the opposite of what happens in the mRNA vaccine for COVID which prevents the immune response that would make us very sick. From this, we know that high levels of inosine are probably not something you would want to put into mRNA vaccines. But it could potentially find utility in other applications where you may want to induce a targeted immune response, like immunotherapy for certain cancers.

“This is a bit like finding a stray puzzle piece. You might not know in the moment of discovery who’s been looking for it, but there’s a good chance that by sharing the finding, someone somewhere will be able to complete their picture.”