UAlbany Professor’s Book Chronicles Life in Fukushima’s Nuclear Aftermath

By Bethany Bump

ALBANY, N.Y. (July 29, 2025) — UAlbany English Professor Thomas Bass was vacationing in Japan in 2018 when a former student, a Japanese journalist, offered to escort him to Fukushima, the site of the major 2011 nuclear disaster. It had been seven years since a tsunami slammed into the coast, killing 20,000 people and destroying the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl.

“Fukushima fascinated me,” he said. “It was a blinking red light on the horizon as I traveled around Japan, because the Fukushima disaster was an astounding event.”

Bass saw thousands of workers scraping up contaminated topsoil in hopes of making the land livable again and hulking incinerators dotting the coastline being used to burn up radioactive materials. He also met with some of the few remaining residents of eerie ghost towns located near the plant whose melted reactors remain deadly, even to the robots that burn up trying to explore them.

On a return visit four and a half years later, a lot had changed. He noticed that topsoil had been scraped into huge plastic bags and hauled to a central dump, while infrastructure including railroad lines, town halls and schools had been rebuilt, and a flourishing citizen science culture had developed as people moved back into the area and learned how to decontaminate their homes, develop new farming techniques, and monitor their food and environment.

Bass shares these observations and more in his new book, Return to Fukushima, which chronicles the Japanese government’s push to resettle more people to the nuclear exclusion zone amid ongoing safety and environmental concerns, as well as the grassroots network of citizen scientists who have emerged and are working to restore health and life amid radioactivity.

An ongoing disaster

Bass’ interest in nuclear disasters traces back to his father, who was a chemist and metallurgist and worked for a company involved in making the triggers on the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The Fukushima disaster was of particular interest to Bass because of its origins and ongoing nature.

“Three Mile Island as an atomic disaster could be dismissed as worker incompetence. Chernobyl could be dismissed as Russian incompetence. Fukushima could not be dismissed,” Bass said. “This was a first world, highly technical country that had not one, not two, but three nuclear reactors melt down and explode, and an astounding amount of radioactivity was dumped into the Pacific Ocean and the countryside surrounding Fukushima. So it really is a technological failure, an industrial failure and a scientific failure of remarkable magnitude. And the fact that the disaster is ongoing is something people just aren’t aware of or want to forget.”

Huge volumes of water are being used to cool the plant, whose reactors continue to release lethal levels of radioactivity that make it difficult to locate the remains of radioactive fuel released during the meltdowns and explosions.

While cleanup continues, the Japanese government has declined to conduct studies measuring the effects of radiation in humans, fish or plants and continues to push people to return to the area — even cutting off housing support for displaced residents and offering perks like lump sum payments and free schooling as a way to lure people back.

Argonauts of the Anthropocene

More than 100,000 people remain displaced from their homes in Fukushima, but some have returned. While ghost towns remain near the reactors, some areas are beginning to see more people move in who are developing ways to live with radiation.

“The number of people who have industrial strength radiation detectors in their houses is quite remarkable,” Bass said.

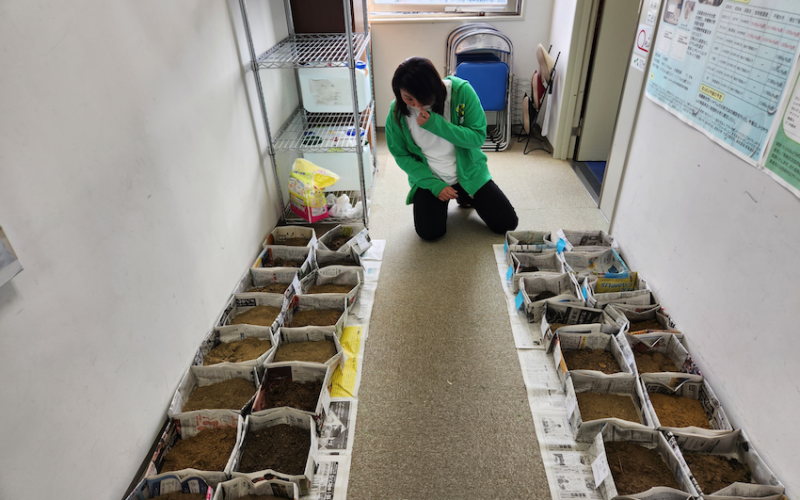

A phenomenon known as the “Fukushima divorce” has emerged, as more men have chosen to return to the area while women prefer to keep their children away, he said. At the same time, citizen science efforts to study radiation levels in places supposedly deemed safe have grown. The Mothers’ Radiation Laboratory, for example, collects and tests soil samples from different resettlement areas, including schoolyards.

“Citizen science is something that Fukushima is at the forefront of at the moment, in terms of just everyday people running radiation laboratories,” Bass said.

Citizen scientists are also exchanging information with the residents of Chernobyl, Ukraine, who continue to live with the effects of radiation from a 1986 nuclear explosion. Bass believes such information exchanges are only going to become more common as the push for nuclear power continues and nuclear exclusion zones that are unsafe due to contamination grow around the globe.

Bass has dubbed residents living in these contaminated areas “Argonauts of the Anthropocene,” which refers to the geological age when human activity began to have a dominant impact on the environment.

“The Anthropocene is the only geological age named after human junk,” he said. “It's dated from the first atomic bomb that was exploded at the Trinity test site in New Mexico. That's the start of the Anthropocene. And the Argonauts are those people who sail off to the unknown world and manage to survive. The people of Fukushima are trying to figure out how to live in this new age.”

Japan is currently in the process of restarting its nuclear reactors. A revived push for nuclear energy is also underway in the U.S., with a new power plant opening in Georgia and plans to reopen the Three Mile Island plant in Pennsylvania on the horizon. Artificial intelligence companies have also begun to buy electricity out of old plants, extending the life of so-called zombie reactors beyond what they were designed to tolerate.

“Human beings have this remarkable capacity to embrace what kills us, whether it's bad technology or warfare or disastrous government or incompetence or whatever,” Bass said. “We're in a perilous state at the moment and Fukushima is just one example of this. But I thought I'd hold it up as one example from which we can learn something, so maybe we can.”