Residential Inequality for Muslims

Muslims in America today encounter stigmas that literally hit home. This is revealed in newly published research by two University at Albany faculty members, who delved into the unexplored area of residential attainment.

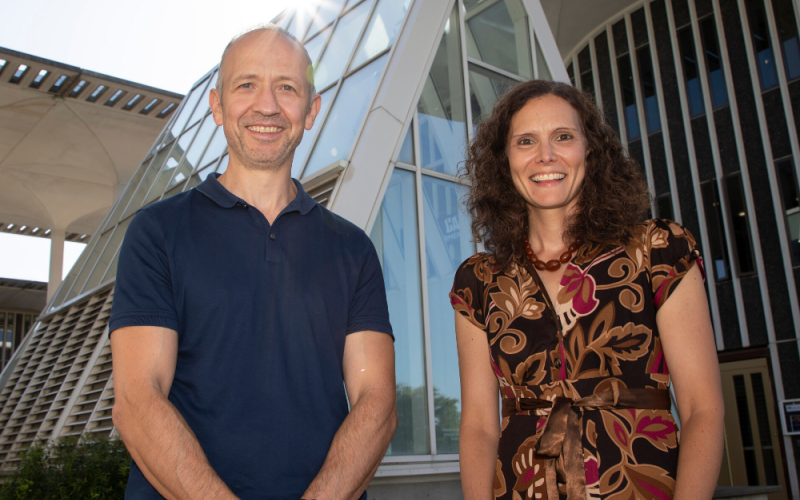

Using Philadelphia, Pa., as their case study, lead author Samantha Friedman of Sociology and co-author Recai Yucel, chair and professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, found that the city’s Muslims are experiencing greater residential disadvantages than non-Muslims. “Moreover,” said Friedman, “black Muslims face a double disadvantage due to race and religion, relative to black non-Muslims.”

Their study, “Muslim-Non-Muslim Locational Attainment in Philadelphia: A New Fault Line in Residential Inequality?,” published in the August issue of the peer-reviewed journal Demography, uses data gathered from household surveys in the Philadelphia metropolitan area from 2004, 2006 and 2008 that deal with people’s religious affiliations, race, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Friedman and Yucel then merged this data with information on neighborhood characteristics from the 2005-2009 American Community Survey.

“Our analyses find significant Muslim-non-Muslim disparities in neighborhood characteristics,” said Friedman. “Black and non-black Muslims live in neighborhoods with fewer white residents than non-Muslims, even after making equal their socioeconomic and demographic characteristics — for example income, education and family status. Among blacks, Muslims are 30 percent less likely than non-Muslims to live in suburban neighborhoods.”

Disparities by Race over Economics

The team did conclude there were not significant disparities with respect to the economic status of neighborhoods once the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of Muslims and non-Muslims were equalized. As such, they found no differences in the neighborhood median household income or poverty level between Muslims and non-Muslims.

“Our results clearly point to the salience of race rather than economics regarding the neighborhood outcomes of Muslims in Philadelphia,” said Friedman. “Muslims are less likely to reside near majority-group members and more likely to live alongside minorities.”

Philadelphia proved to be an ideal city to assess the extent to which both race and religion shape residential attainment. It reflects national trends in that Muslims account for just over 1 percent of the population, but unique to the Philadelphia area is that the majority of Muslims are black, compared with 20 percent at the national level. The metropolitan area ranks fourth nationwide in the number of mosques.

“Like previous urban research, we focus on the racial composition and economic status of neighborhoods to measure individuals’ residential attainment,” said Friedman. “A neighborhood’s economic level has important consequences for individual wellbeing. The racial composition of the neighborhood gauges people’s access to society’s majority and minority-group members — particularly important in the Philadelphia metropolitan area.”

Filling in the Gaps of Where Muslims Live

Friedman notes that urban scholars have had a long-standing interest in where people live, because neighborhoods afford their residents connections to a society’s majority members, economic and educational opportunities, and enhancements to health and quality of life.

“Yet, despite growing animosity towards Muslims, we know very little about the kinds of neighborhoods where they live,” she said. “Because we lack data on where people of different religious backgrounds live in the United States, Muslims’ residential patterns have remained absent from these studies.”

The Philadelphia surveys allowed the authors, through intense statistical analysis, the opportunity to bring patterns to light. “The methodologies used in the paper were very complicated, and without Recai’s expertise, we couldn’t have done the study,” said Friedman. The duo were aided by two former UAlbany Ph.D. students, Colleen Wynn and Joseph Gibbons.

While their study does not clearly establish the causes of such disparities, Friedman believes it is likely that anti-Muslim sentiment documented elsewhere impacts Muslims’ residential opportunities. “For instance, our findings are consistent with other research that has found housing discrimination against people with Arab-sounding names,” she said.

“What is striking about our study are the findings for black Muslims. They face a double disadvantage based upon their race and religion by residing in neighborhoods with fewer whites, more blacks, and that are less likely to be located in suburbs.”

She said one important step to reduce inequalities would be to raise Muslims’ awareness of the protections afforded by the Fair Housing Act, “so that they can actively file housing discrimination complaints. Another step would be for fair housing organizations to proactively monitor discrimination against Muslims in local housing markets. Only when these injustices are exposed and challenged can we ensure that Muslims have fair and equal access to housing in Philadelphia and elsewhere in the U.S.”