New Study: Meat May Not Have Made Us Human, After All

ALBANY, N.Y. (Jan. 27, 2022) — The importance of meat-eating in human evolution is being challenged by a new study from a team of five paleoanthropologists that includes the UAlbany’s John Rowan.

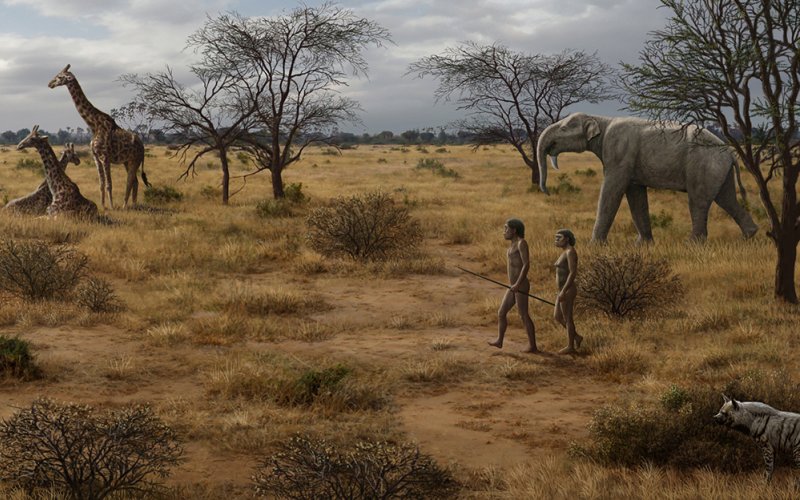

For decades, researchers have causally linked an evolutionary shift towards greater carnivory to the appearance, approximately 2 million years ago, of Homo erectus. The advanced biology and anatomy of this species, including large brain size, and its association with large caches of cut-marked animal bones have provided the main line of evidence for the “meat made us human” hypothesis, making it conventional wisdom in human origins research.

Now the team of researchers, in a paper published in the Feb 1 issue of PNAS, the official journal of the National Academy of Sciences, says their analyses indicate that key evolutionary milestones, including an increase in brain and body size, a reduction in gut size and modern human-like limb proportions, did not come about because of increased meat consumption.

Led by Assistant Professor Andrew Barr of George Washington University, the team analyzed temporal patterns in the quantity of published evidence for hominin carnivory between 2.6 million and 1.3 million years ago from 59 sites across major research areas in eastern Africa. Controlled for sampling efforts, their results showed no sustained increase in cut-marked animal bones after the appearance of H. erectus.

“We agreed that the key problem with the ‘meat made us human’ hypothesis is that all fossil and archaeological records have temporal gaps or periods of time that are better sampled than others,” said Rowan, who, in addition to helping conceive the study and its analyses, served as its chief paleontologist, due to his expertise in the African fossil record of human ancestors.

He described the period just after 2 million years ago as being “very well sampled” in eastern Africa, especially in Kenya and Tanzania, whereas the preceding million years is one of the most poorly known.

“Thus, we considered it possible that the increase in evidence for carnivory around 2 million years ago simply reflects a much better sampled empirical record and shouldn’t be taken at face value as signifying a major shift in our ancestors’ diets.”

The research team collected several independent measures of empirical record quality to compare with the quantity of evidence for carnivory. They found that all of these control measures closely tracked the quantity of evidence for carnivory, and in fact characterized all of the eastern African fossil and archaeological record from 2.5 to 1 million years ago — strongly suggesting that an increase in hominin carnivory after 2 million years ago was merely a sampling artifact, with other factors likely responsible for the appearance of human-like traits.

“The key take-home is that we currently have zero evidence for a shift in the prevalence of hominin carnivory through time, including the period when Homo erectus shows up,” said Rowan. “All of the ‘patterns’ we see are shaped by the quality of the record.”

The paper’s authors — Barr, Rowan, Briana Pobiner of the Smithsonian, Andrew Du of Colorado State University and Tyler Faith of University of Utah — have worked and published together for several years on a number of related topics.