Study: Decreasing Wildfires Observed Over Central Africa

ALBANY, N.Y. (Sept. 24, 2020) – Referred to as the “fire continent” by NASA, Africa is surprisingly a crucial hot spot for blazes. Global satellite images have shown that on an average August day, it is home to at least 70 percent of the 10,000 wildfires burning worldwide and 50 percent of fire-related carbon emissions.

However, a new observational study has revealed a decreasing burned area trend that could impact African ecosystems.

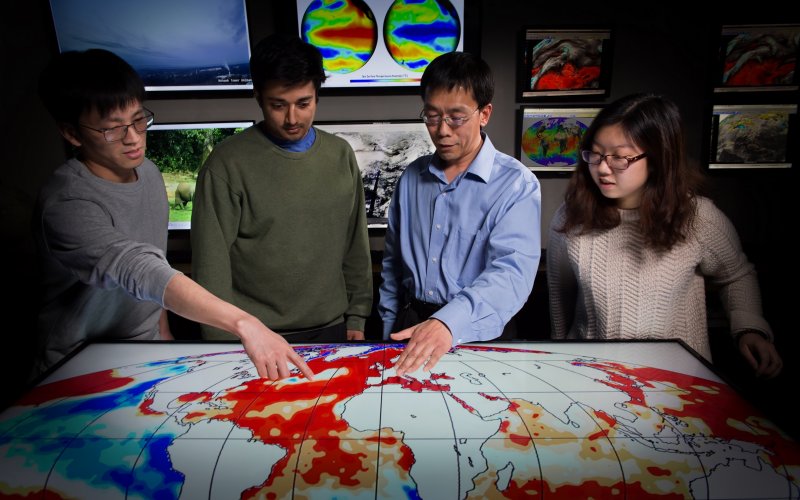

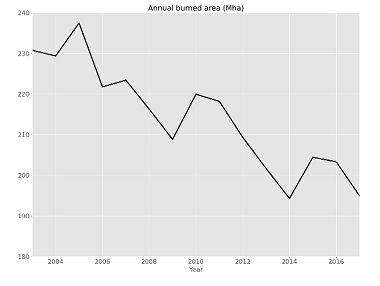

The study, led by a team of researchers in the Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences (DAES), analyzed fires in Central Africa from 2003 to 2017 using a combination of satellite-derived burned area data, reanalysis data, and machine learning techniques. Results showed a total decline in burned area by about 1.3 percent per year. The decline, both in fire frequency and size, occurred mostly in tropical savannas and grasslands. A small increase in burned area was observed over the southern edge of the Congo rainforest.

Findings were published this month in Environmental Research Letters.

“Wildfires can be hugely destructive, particularly to forest ecosystems, but also play a crucial role in maintaining ecological function and health,” said Liming Zhou, DAES professor and study co-author. “Naturally occurring fires are important for controlling vegetation growth and patterns for grasslands, savannas, and shrublands, and are integral for the maintenance of these ecosystems and supporting a large range of endemic species.”

Fire and Climate Change

Climate in Central Africa is characterized by a strong precipitation gradient between the Sahara, the world’s largest and driest desert, and the Congo Basin, the world’s second-largest tropical rainforest. The area is extremely rich in biodiversity and encompasses ecosystems that are sensitive to wildfires due to weather shifts and human activities, according to the researchers.

Less flammable vegetation, due to climate change in Central Africa, is suggested to be the leading cause for the observed burned area decreases, according to the study. The finding adds to a previously documented long-term drying trend and increasing dry season length over the Congo Basin since the 1980s.

Although warmer and drier conditions with longer dry seasons tend to increase the risk, spatial extent, and duration of wildfires, the impact on fire is difficult to predict due to a number of climatic and anthropogenic factors, according to the researchers. Combining the latest satellite products and machine learning techniques enabled them to better untangle the region’s complex fire-climate-ecosystem interactions, which could have profound implications for future local societal development and fire management.

“We are surprised to find that suppressed flammable biomass was the leading cause for burned area decreases in savannas and grasslands,” said Yan Jiang, the study’s lead author and DAES graduate student. “Our results are consistent with the positive correlation between vegetation greenness and precipitation amount in local savannas and grasslands. Another key finding is that burned area changes in savannas, grassland, and rainforest edges over Central Africa are likely natural and not caused by the clearing of forests and agricultural activity.”

“Although we are not the first to report the decreases in burned area in Central Africa, our work advances this scientific knowledge by attributing the changes using machine learning techniques,” added Ajay Raghavendra, a study co-author and DAES graduate student. “We were also able to include the impact of lightning, which is a major ignition source for fires in Central Africa, using data from our previous work.”

The researchers plan to continue improving their analysis to include small fires that are not detected by the satellite data and separate the natural and anthropogenic factors that contribute to the wildfires. Their research is funded by the National Science Foundation.