NYS Writers Institute, December 5, 1996

4 p.m. Reading | Recital Hall, Performing Arts Center

A leading evolutionary biologist, Stephen Jay Gould is admired by specialists and general interest readers alike for explaining difficult scientific theories in writing which is accessible, but never trivializing, and always entertaining. Gould is the author of 15 books, most recently, Full House: The Spread of Excellence from Plato to Darwin. Full House, which teaches the science of reading trends via a celebration of biodiversity, is his first single subject book since the New York Times bestseller Wonderful Life (1989).

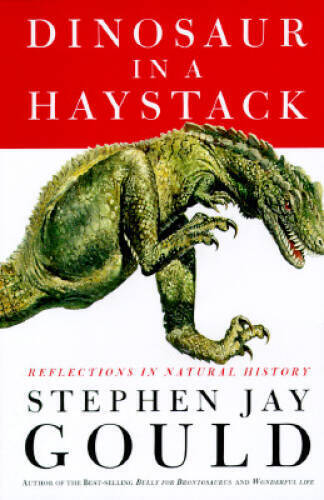

Gould's critical examination of IQ testing, The Mismeasure of Man (1980), won the National Book Critics Circle Award. Since 1972, Gould has written a monthly column for Natural History magazine, yielding seven collections of essays including the best-selling Dinosaur in a Haystack, published in January of this year. An earlier collection, The Panda's Thumb (1980), won the American Book Award.

Reflecting his belief that science is a "culturally embedded" discipline and a "creative human activity," Gould's writing knits together arcane and amusing details drawn from a wide range of sources. New York Newsday praised his "gift for metaphor for finding striking analogies that highlight the organizing principles behind Nature," and John Updike, said in The New Yorker, "Gould's prose pebbles make addictive reading." Gould's unique combination of technical brilliance and popular appeal moved one Washington Post reviewer to comment, "In a culture where 'intellectual' is often a term of reproach, Gould may be just the one to restore its good name."

Gould is the Alexander Agzassiz Professor of zoology and professor of geology at Harvard, where he is also the curator for invertebrate paleontology at the university's Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Cosponsored by Guilderland Central School District "Goals 2000"

Additional information:

Stephen Jay Gould: So Smart, It’s Scary

By Paul Grondahl, M.A.’84

Stephen Jay Gould spoke at the University at Albany on December 5, 1996 as part of the New York State Writers Institute's Visiting Writers Series.

The following article by Paul Grondahl appeared in the Spring 1997 issue of Albany, the University's magazine.

The bookish boy who loved dinosaurs, taunted mercilessly by the other kids as “fossil face,” has been savoring his sweet revenge ever since. Fifteen minutes before the scheduled start of his lecture at four o’clock in the afternoon on a wintry December Thursday at the University at Albany, Stephen Jay Gould had filled the main theatre of the Performing Arts Center beyond capacity, with dozens of students sitting shoulder-to-shoulder in the aisles.

There was a palpable buzz of excitement in the air as the crowd awaited Gould. After some squeezing and repositioning to safely accommodate more than 600 fans of the work of the Harvard University evolutionary biologist -- who has discussed complex scientific notions for the attentive reader through the course of 13 acclaimed books and an unbroken 22-year streak of monthly columns in Natural History magazine -- the great Gould was ready to begin.

Almost. Gould has earned a reputation for being difficult and, as one example, he forbade the taking of photographs during his speech. When a camera flash pierced the auditorium, Gould stopped and seethed. Like a temperamental maestro, Gould brooks no interruptions and received no more during an hour-long reading of a previously published Natural History essay on the evolution of horses, accompanied by his own lively commentary that formed a kind of essay-within-an-essay.

In typical Gouldian fashion, his discussion of evolution drew together a constellation of seemingly disparate sources -- from Shakespeare to the television show “Dragnet,” from Darwin to “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” -- that o’erleaped the confines of logic to form their own brilliant connections and universal truths. It’s as if he rummages around in the vast attic of ideas in his mind and alchemizes the dross into gold.

Gould defies classification: paleontologist, geologist, biologist, evolutionary biologist and Renaissance Man all have been used as shorthand modifiers, but each fails to encompass the essential Gould oeuvre. He’s so smart it’s scary.

In collaboration with paleontologist Niles Eldredge, Gould formulated the important evolutionary theory of “punctuated equilibrium,” modifying Darwin in a way that sees non-change as the norm, with nature offering rapid and sweeping permutations in small segments of a species rather than by the slow and steady transformation of entire ancestral populations.

The theory blows holes in the commonly held notion of evolution as a relentlessly upward climb with humans at the top. The extinction of dinosaurs, for instance, occurred in response to an event rather than a slow, drawn-out inevitability, according to Gould. In books such as Flamingo’s Smile, he celebrates the importance of randomness and unpredictability in the history of life.

“We’re not as powerful as we think,” Gould told the University audience, noting humans are an oddly singular and tiny evolutional blip on the radar screen, separated from other mammals only by our consciousness, and badly outnumbered, for instance, by the million or so species of arthropods alone. “We have no right of domain over this planet. We’re latecomers compared to bacteria, which have always been here and are going to beat us for sure. Humans are just one species struggling along and we’d better work together to keep it going.”

Gould’s visit was the last reading in the fall visiting writers series sponsored by the New York State Writers Institute, and after his reading, he was swallowed up just off stage by fans thrusting books at him. “I won’t sign them here,” he said. A high school student whispered to a friend as he was swept along in the pack vying to get close to Gould: “It’s like he’s the president or something.”

He didn’t look presidential. Gould looked beleaguered, clutching the same large, heavy black briefcases bulging with books -- one in each arm, as if to achieve a kind of equilibrium -- that he lugged along during a visit to the University in 1991 for the Writers Institute’s “Telling The Truth” conference. It’s good to see age (he’s 55 now) hasn’t softened Gould; he wouldn’t grant interviews then and he won’t grant interviews now. Gould remains in all things his same uncompromising self.

To be fair, Gould was loose and generous -- even jocular -- when meeting privately with a small group of students from a biology class at Guilderland High School prior to his public reading. He lounged on a stage, his stout body sprawled childlike across the floor, dressed in rumpled chinos, brown penny loafers, blue dress shirt and brown tie with a diamond pattern. He smiled, laughed and brushed back his thick helmet of silvery hair as he told the students about how he would ride the subway with his father from their home in Queens to the American Museum of Natural History on Manhattan’s Upper West Side beginning at age five.

The young Gould was mesmerized particularly by the skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex, gripped by a mixture of awe and fear. In adulthood, he would revisit such formative experiences in, among other books, Dinosaur in a Haystack and Bully For Brontosaurus. “I guess I sort of fulfilled what I was meant to do since age five,” Gould told the high school students.

From a passion for dinosaurs, he graduated to collecting shells at age eight at Rockaway Beach, and then to hunting for fossils as a teenager. After majoring in geology and earning a bachelor’s degree at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, Gould earned a doctorate from Columbia University in 1967 for work in geology and invertebrate paleontology. He’s been teaching at Harvard University since 1967 and holds the position of curator of invertebrate paleontology for Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology.

In his personal life, he’s endured his share of painful random events. Gould is the father of an autistic son. His marriage of 30 years broke up (he has since remarried). He was diagnosed in 1982 with a deadly asbestos-linked cancer, abdominal mesothelioma, with a median mortality of eight months. After surgery and chemotherapy treatment, Gould is in remission. He once described himself as “a tough cuss.” As a writer, he’s that rare species, author of books on paleontology and the history of science that are best-sellers and highly regarded among scholars.

He’s done for fossils and dinosaurs what Carl Sagan has done for the stars. In doing so, Gould has won the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Phi Beta Kappa Science Award and was among the first recipients of the MacArthur Foundation’s so-called “genius” grant.

“I write these essays primarily to aid my own quest to learn and understand as much as possible about nature in the short time allotted,” he wrote in the introduction to The Flamingo’s Smile, his 1985 collection. “Every month is a new adventure -- in learning and expression.”

Gould is eminently quotable, but two notions from his 1993 book, Eight Little Piggies: Reflections In Natural History, offer a window onto Gould’s accomplishments. “Extinction is the ultimate fate of all and prolonged persistence is the only meaningful measure of success,” he wrote. Also, “Details are all that matters: God dwells there, and you never get to see Him if you don’t struggle to get them right.”

“I’m a total autodidact as a writer,” Gould confessed to the University audience. The essay Gould read, “Mr. Sofya’s Pony,” chronicled the career of an obscure 19th-century Russian paleontologist, Vladimir Kovalevsky, who died young after publishing just six scholarly papers between 1873 and 1877, but was the first to work out the evolution of horses.

Kovalevsky’s hapless life was marked by a marriage of convenience so that he and his wife, Sofya, a brilliant mathematician, could emigrate from Russia. They settled in Germany, where they lived and worked in different cities. After going broke from bad business deals, Vladimir, who suffered from mental illness, fell into a deep and prolonged depression and committed suicide in 1883 by putting a bag with chloroform over his head.

Among vertebrate paleontologists, however, Vladimir’s wondrous theory of horses evolving from many-toed ancient ancestors to a single-toed modern animal lived on as a classic of correlating evolution to a change in environmental conditions -- namely from soft swamps to hard plains.

Vladimir’s observations were championed by esteemed evolutionary biologists, including T.H. Huxley and Charles Darwin himself. After 45 minutes of prelude reading the essay, Gould told the audience with a gleam in his eye, “This is a literary device. I’m setting you up.”

In the essay’s concluding section, Gould turned the tables. “Vladimir was wrong,” he said, noting the Russian studied only European fossils, a peculiar side branch-horse species, while the real evolution of horses had occurred in America. Huxley and Darwin noted Vladimir’s wrong assumptions and went on to revise and build upon the obscure Russian’s groundbreaking, albeit flawed, research.

“It was a fruitful error,” Gould said. “It was a case of being right for the wrong reason, an eminently useful and wonderful mistake.” The moral of Gould’s story: “Great truth can emerge from a small error.”