Izapa and the Development of Early American States

ALBANY, N.Y. (May 27, 2021) — In the grand history of humanity, several empires have come and gone, often leaving an indelible mark on our world. But hundreds of thousands of smaller states have also existed, and their role in shaping the world we live in today is long overdue for a review, according to University at Albany archaeologist Robert Rosenswig, in a new research article for American Anthropologist.

Rosenswig presents a case study from Mesoamerica’s southern Pacific coast from about 2,300 years ago and looks at how the communities traced to that location and time period provide a window into how past societies were formed, particularly in relation to their neighbors.

He concludes that the vast majority of hierarchical organized societies that have existed on Earth — what we would refer to as kingdoms — were contained within a distance that could be traveled in a single day and so facilitate face-to-face interaction.

“In particular, we look at the formation and organization of the Izapa kingdom in southern Chiapas, Mexico, and how it is described and contrasted with its neighbors,” said Rosenswig, a professor of Anthropology at UAlbany. “Each of these communities had a compact and discrete arrangement of hierarchically organized political centers that shared architectural arrangement within each kingdom that contrasted with each other.”

Rosenswig points out how today’s major empires — the United States, China, and Russia — are only 1.5 percent of the 21st century’s sovereign nation-states. Their global influence may be readily apparent, but they also only represent a tiny fraction of the 193 seats at the United Nations.

This has also been true throughout world history. But away from the core polity, distant territories/colonies can be variously administered and precariously controlled.

“I leave the discussion of sovereignty within empires aside in this article,” said Rosenswig. “Instead, I focus on the vast majority of hierarchically organized human pluralities that experimented with sovereignty that are much smaller. These small polities, which surely number in the six figures, are the focus of this article.”

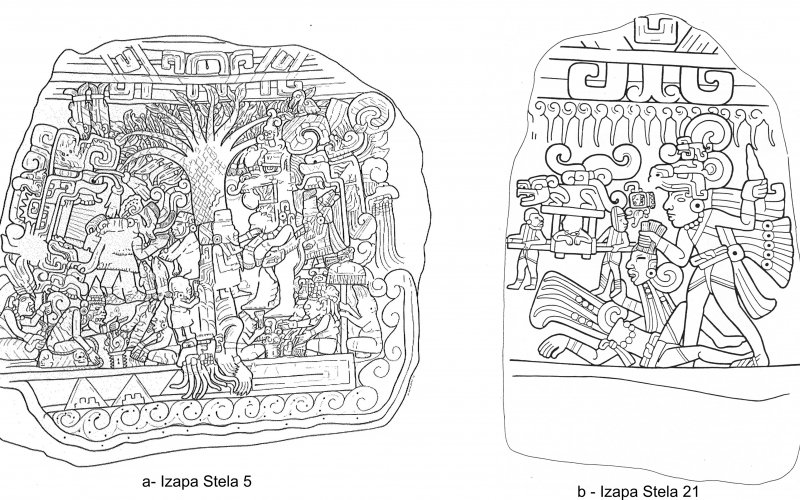

During the final centuries before the Common Era, a network of kingdoms existed along the Pacific coast of Mexico, Guatemala and El Salvador. Large earthen mounds that formed plazas lined with stelae, elaborately carved in a shared art style, defined each kingdom’s capital city. In the case of Izapa, Rosenswig has conducted extensive research on the archaeological site located along the Izapa River, where a pre-Columbian kingdom was once situated during the Late Formative period (roughly 300 BC to 100 AD).

In the study, Rosenswig reviewed how Izapa and the mounds of neighboring kingdoms are reflective of the “30 km rule,” which is defined as a cross-cultural pattern for the spacing of sovereign polities. The rule is confirmed based on the location of Izapa and neighboring Pacific coast kingdoms, a trait shared in common by nation-states found in the Syro-Anatolian Iron Age, as well as the Classical Maya period and Medieval Europe, with polities all demonstrating a similar spatial organization.

How were these kingdoms formed? Rosenswig notes how the moral and philosophical justification for modern nation-state sovereignty is democracy.

“In earlier times, a variety of gods granted rulers the moral mandate to govern as well as make and enforce laws. In earlier societies, a human sovereign embodied divine political authority,” Rosenswig said. “As the epigraph emphasizes, such divine authority still forms the basis of most 21st century nation-states. Sovereign states in the ancient and modern worlds are therefore less different than some assume.”

We now understand that the Izapa kingdom was a tightly integrated sovereign territory of about 450 square kilometers for six centuries (700–100 BC), but the site remains best known for its carved stone stelae erected during the final two of these centuries.

Similarly distinctive architectural traditions suggest that Izapa, El Ujuxte and Takalik Abaj were each independent kingdoms, and so does the spacing between these polities. Their distance from each other, as well as further southern settlements of Takalik Abaj and Chocolá were all roughly 30 kilometers apart.

“This puts all five capital cities of the Late Formative period Pacific coast kingdoms beyond the 30 km threshold of one-day return travel. Such spacing implies a kingdom’s authority and military power were focused on the king and his retinue stationed at a capital,” Rosenswig said. “So, while it may be possible that other factors define sovereignty, the kingdoms that coalesced on the southern Pacific coast of Mesoamerica during the first millennium BC provide evidence of sovereign territories arranged according to the 30 km rule.”

Kingdoms from across the globe and through the ages show a surprising degree of consistency in their spacing and organization. Rosenswig has argued that one day’s travel by foot (about 60 km) provides a structural limit for direct political control and defines a 30 km rule for the minimal spacing between sovereign polities While ancient Rome or the vast Aztec Empire surrounding Tenochtitlan are notable exceptions, virtually all hierarchical societies that have ever existed on Earth have been organized around the limits of one-day return travel time.

“The case of southern Pacific Mesoamerica is instructive, and I presented evidence that Izapa was a sovereign kingdom with a coordinated hierarchy of political centers, distinct borders and state-sanctioned violence and that neighboring polities were spaced from each other according to the 30 km rule,” concludes Rosenswig. “The interpretation of Izapa and its neighbors do not rely on assumptions of one-day travel to infer their sovereignty but instead provide a detailed case study that confirms that this cross-cultural pattern was operating in southern Pacific Mesoamerica during the second millennium BC.”

Izapa is one among hundreds of thousands of ancient kingdoms that have existed on Earth during the past five or six millennia. Like most of the others, archaeological evidence is the only way that we can access such early experiments with sovereignty and territoriality that define the modern world.

Further reading: Rosenswig’s research is also featured in the May/June 2021 issue of Archaeology Magazine: “Exploring the Kingdom of Izapa: An overlooked people living between the Olmec and Maya worlds were a cultural force far beyond their realm.”