UAlbany Professor Awarded Yale Fellowship for Research on Ukrainian Liturgy

By Bethany Bump

ALBANY, N.Y. (May 25, 2023) — As the daughter of an Orthodox Christian priest, Nadia Kizenko became familiar early on with liturgy — the rites and rituals involved in public worship by members of a religious group.

“Basically if you’re a preacher’s kid, you are kind of like a member of a theatrical troupe,” she said. “Your job is to put on a show and deliver an experience for everybody else.”

As a young girl, Kizenko sang in the choir, read Psalms aloud, and helped her family work through the more technical components of services at St. Vladimir Memorial Church, a Russian Orthodox Church in Jackson, N.J.

“Do we do the blessing of the water in a covered tent in front of the church to make it more convenient for older people in the heat?” she said. “Or do we walk in a procession down to the lake, more like the way they do it in historically Orthodox countries like Russia, Ukraine and Belarus? Do we sing this hymn or that hymn? Do we stand or fall to the ground?”

Kizenko, a professor of history and director of the Religious Studies Program at UAlbany, has always been fascinated by questions related to liturgy. This fall, she will have the chance to blend that interest with her expertise in Russian and Ukrainian history, culture and religion as a Fellow of the Yale Institute of Sacred Music (ISM), where she will study changes in Orthodox liturgy in Ukraine after the fall of the Soviet Union and especially in response to Russia’s invasion in February 2022.

As part of the ISM Fellows program, Kizenko will spend the 2023-24 academic year in New Haven as a senior research scholar and will have access to Yale’s collections and resources, as well as proximity to other scholars who are thinking seriously about religion and liturgy.

“There’s very few academic departments in the United States where you can study liturgy in a comparative context,” she said. “Most people are in a history department like me, or they might be in a music department, or maybe a department in theology, maybe even theater. But there are very few places where you can put it all together. This is so specialized that it’s actually a great opportunity to be able to think about religious texts and religious ceremonies in a secular context with other secular specialists.”

With respect to Ukraine, Kizenko has been thinking about what it means when a church is linked to a specific nation versus proclaiming the “universal good news.” In Ukraine, the two canonical Orthodox churches had different attitudes toward Russia prior to the attack, she said, and changes to their liturgies in the aftermath have made those differences more overt.

The Orthodox Church of Ukraine and Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, for example, claim to be the most authentically Ukrainian expression of Christianity with liturgies in vernacular Ukrainian that emphasize the nation’s long colonial victimhood at the hands of its imperial and Soviet-era Russian masters. Liturgical updates after the invasion included new prayers for victory and for wisdom.

The situation was more complicated for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the Ukrainian exarchate formerly in communion with the Russian Orthodox Church, which had been more focused on the elements it shared with its Russian co-religionists and on Ukrainian contributions to an “all-Rus” and Russian imperial tradition, Kizenko said.

But inflammatory sermons by Patriarch Kirill of Moscow after the Russian invasion seemed to trigger an identity crisis for the church, she said. This was reflected in the liturgy when many UOC priests and bishops defended Ukrainian sovereignty, denounced the war, and opted not to commemorate or even denounce Patriarch Kirill. In May 2022, the church declared its independence from Moscow.

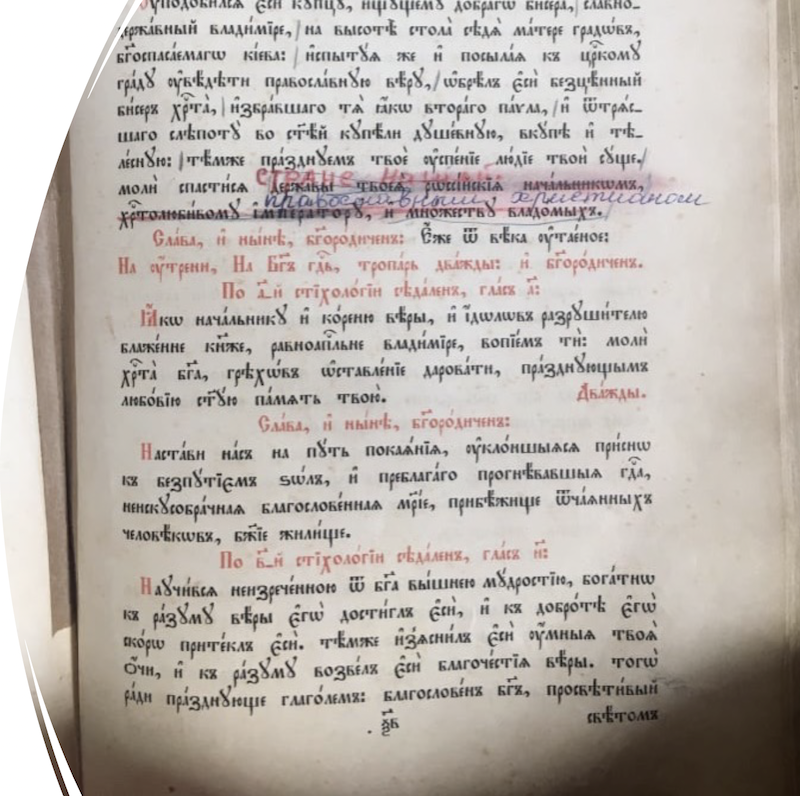

The issue of language also comes into play. At the Russian Orthodox church Kizenko attended, services were done in Church Slavonic, a liturgical language shared with other Slavic groups (especially Serbs and Bulgarians). Even Ukrainian Catholics did services in Church Slavonic until Vatican II, when they switched to modern Ukrainian. After February 2022, the UOC has introduced more Ukrainian.

"The issue is whether one takes Church Slavonic to express a shared Slavic heritage (this is the position of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church), or a connection to the Russian empire and to the contemporary Russian Orthodox Church (as does the Orthodox Church of Ukraine), not because it is Russian (it is not), but which associations with it one has," she said.

Kizenko hopes to explore these liturgical changes in depth, exploring the ways in which politics and national trauma can become infused in a wide range of liturgical decisions, such as which hymns, melodies and musical settings to use and which national saints and feasts to venerate or demote.

“It’s really just asking the question of how does a liturgical tradition change in response to war?” she said. “Should church be a place that is a refuge from the turbulent world of politics? Should it give you a larger perspective? Or should it be the place where political passions are also played out?”

The questions are interesting to Kizenko in part because the Orthodox liturgical tradition is so conservative — and so historically linked to the nation or the figure of the ruler.

“These aren’t people who run around changing things at the drop of a hat,” she said. “So when they change things it’s actually a really big deal.”

“In the largest sense, I am looking forward to thinking about what makes people welcome or accept or resist changes in liturgy — and in the company of fellow ‘liturgics nerds’ who are thinking about the same thing,” she said.