Far-Right Extremism in America: A Q&A with Sam Jackson

ALBANY, N.Y. (July 21, 2022) — Sam Jackson, an assistant professor at the College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity, studies far-right extremism in America, including antigovernment groups and issues and responses related to online extremism.

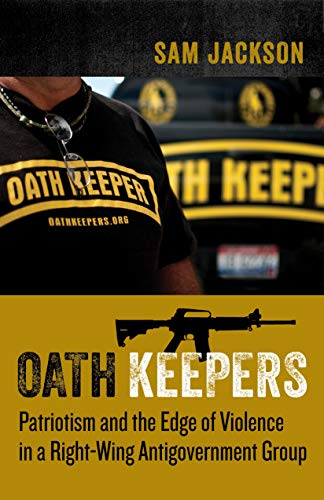

In September 2020, Jackson published “Oath Keepers: Patriotism and the Edge of Violence in a Right-Wing Antigovernment Group.” The Oath Keepers are among the most visible and vocal far-right wing antigovernment groups in the United States, and Jackson’s book takes readers inside the Oath Keepers’ world, examining its extensive online presence to discover how the group has built support for its political goals and actions.

Media outlets, including The Washington Post, CNN, Newsy, CBC and the National Journal, turned to Jackson for his expertise as the Oath Keepers were thrust into the spotlight following a former spokesperson of the group testifying at the Jan. 6 committee hearing last week.

We caught up with Jackson to learn more about the rise of far-right extremism in the United States, his book on the Oath Keepers and current research.

How do you define far-right extremism in America?

There is disagreement among scholars about how to define the far right (or right-wing extremism or the extreme right or the radical right — lots of near synonyms exist in this space). For me, right-wing extremism refers to activity that, in reaction to a perception of negative change, aims to revert fundamental features of the political system to some imagined “golden age” from the past. The most important forms of right-wing extremism in the U.S. organize around a perceived racial identity and crisis faced by that racial identity. But some groups – including the Oath Keepers – do not organize around race; instead, these groups organize around a perception that the federal government is tyrannical and that good, patriotic Americans need to be ready to fight back, possibly with violence.

Why did you decide to write a book about the Oath Keepers over other similar antigovernment groups, such as the Proud Boys?

Since 2009, Oath Keepers have been arguably the biggest and most important faction of what I call the patriot/militia movement — a far-right movement in the U.S. broadly motivated by a perception of governmental tyranny and that the country’s problems stem from being insufficiently faithful to the political system created by the Founders in the 18th century.

I started my research on Oath Keepers in 2015, before the Proud Boys were even formed. At that point, the group was in the middle of a series of so-called “security operations” and standoffs with different government agencies. Then, and still now, there is a too common misperception that antigovernment groups are just undercover racists. It’s certainly true that there are some vile through lines of bigotry among Oath Keepers members (especially regarding Islam and immigrants). However, there’s an important difference between ideologically racist organizations and movements and antigovernment groups and movements that genuinely believe themselves to be color blind.

If we want to design interventions to reduce the problems of right-wing extremism, we need those interventions to speak to the ideas that lead people to get involved in the first place. If we take someone who believes themselves not to be racist and say, “you’re just another white supremacist,” that could lead them to double down, believing that if they’re going to be portrayed as racists no matter what, maybe they should just ignore anyone who disagrees with them. One of the goals of my research is to understand the ideas that matter to people in these groups and movements.

Your book has gained national attention since the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. Given your extensive research on the Oath Keepers and other similar groups, was that day surprising to you?

To be honest, I don’t remember how I felt that day; my thoughts leading up to that day have been entirely overwhelmed by what I’ve learned since then. I wasn’t doing the kind of detailed monitoring of extremist chatter that some others were doing, so I don’t think I knew that Jan. 6 was going to be a big day, but at the same time, this kind of activity wasn’t surprising. Oath Keepers spent years saying that America faces an existential threat from domestic enemies of the nation, and by the end of 2016 they were fully on the Trump train; so even if I couldn’t have predicted the day that this would happen, I wasn’t surprised that it happened at some point.

As I wrote with a couple of colleagues, the Jan. 6 insurrection revealed what the group has always been: an organization that has “weaponized patriotism in an effort to subvert American democracy.” That didn’t start with the insurrection, and I wouldn’t expect it to end with the insurrection either.

Do you believe the mainstream media’s increased coverage of far-right extremism in America has helped or hurt these groups?

That’s an interesting and complex question. Some days, I think the world would be a better place if we ignored a lot of these groups and the activities they engage in. But as a social scientist, I want to better understand the world we live in, and deliberate ignorance isn’t compatible with that. And even if the mainstream media ignored these actors and actions, there is a huge so-called “alternative media” — think of outlets that promote mis-/dis-/mal-information like InfoWars and Epoch Times — that will promote these extremists to their scarily-large audiences.

Instead of thinking about whether media outlets do and should cover them, we should think about how media outlets do and should cover them. And this is really tricky. For one thing, plenty of extremists are actually pretty media savvy — they manipulate journalists who don’t have enough experience writing about extremists (for example, we see hoaxes over and over around mass shootings that “Sam Hyde is the shooter”). Even when they aren’t straight up manipulating journalists, they can use media coverage to spread their brand. I can’t help but call out this 60 Minutes segment on Oath Keepers, where they interviewed members of the group in Arizona on camera with an Oath Keepers banner — with contact info — behind them in the shot.

I follow the lead of insightful scholars like Whitney Phillips, Joan Donovan, and danah boyd who argue that the media needs to be very careful about how they cover extremists of all stripes. Phillips points out that coverage can provide extremists with the “oxygen of amplification” that can help them grow. And using the evocative phrase “strategic silence,” Donovan and boyd remind us that some media outlets made very deliberate choices about how to cover bad actors like the KKK and the American Nazi Party to reduce the chances that their coverage could actually help them. I think we can also apply the lessons of the “No Notoriety” movement that encourages media and public figures not to name mass shooters, based on the logic that many of these attackers want to become famous and we shouldn’t give them what they want.

More broadly, I think the media has had to wrestle for the past few years in particular with how to cover people and ideas that are hostile to democracy, from Trump to insurrectionists. We hear a lot about how a “both sides” version of the norm of impartiality among journalists leads to ridiculous false equivalencies: For example, the coverage of the laptop reported to have belonged to Hunter Biden vs. the documented wealth accumulated by the Trump family and its businesses while Trump was in office. Some journalists have learned a lot from how Trump was covered, but some haven’t. I hope we’re also past all the “Nazi next door” style profiles of extremists, but I’m not particularly confident in our collective ability to remember hard-learned lessons.

What are you working on now? Should we expect another book in the near future?

No plans for another book right now. The next big project for me is a collaboration with Brandon Gorman and Mayuko Nakatsuka in the Department of Sociology to investigate QAnon on Twitter. We have a huge dataset (more than 100 million tweets) that spans multiple years. One of the first questions we are exploring is how QAnon spread across the world to other political contexts. We see users with ties to Japan, Saudi Arabia, and many more applying QAnon ideas to their own political communities. How did they learn about the QAnon ideas? How did they decide to incorporate them into their understandings of their own contexts?

I’m also really interested in thinking more about what we saw on Jan. 6. One thing that caught my attention was the coalition of actors present at the insurrection who don’t necessarily agree with one another in pretty fundamental ways. In the past, for example, Oath Keepers refused to participate in events that they believed would have a large presence of white supremacists, given the group’s long-standing desire to not be understood as a racist organization; but by Jan. 6, they were quite happy to riot alongside them. Add to that coalition the confusing mix of QAnon advocates and those I’ve thought of as rank-and-file Trump supporters, and you have quite a mix of ideas motivating people to disrupt one of the basic foundational processes of our democracy. Why were these people willing to work together on that day? And can we identify characteristics of the ideas and of the perceived crises that motivate extremists that would help us anticipate future events where extremists of different ideological orientations cooperate?