The RNA Institute: Distinguishing UAlbany

in Life Sciences Research

By Jill U Adams

Photos by Gary Gold ’70

Muscular dystrophy, antibiotic resistance, breast cancer, arthritis. These disparate diseases have something in common, something beyond biology gone wrong.

“Central to all that bad biology is RNA,” says Paul Agris, director of the newly christened RNA Institute expansion at the University at Albany.

A quick primer for the non-biologists out there: RNA is a kind of middleman between DNA and proteins. Our genes are made of DNA and represent the blueprint for all our features and predispositions. Proteins are the workhorses of the cell; they include enzymes, hormones and structural components.

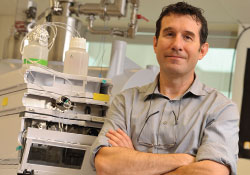

Professor of Chemistry and Biology Daniele Fabris is the director of the RNA Mass Spectrometry Center, part of the RNA institute.

The job of RNA is to “transcribe” the DNA information and “translate” it into proteins. In the realm of scientific research, however, says chemistry professor Dan Fabris, “RNA is a little neglected.”

Some researchers have studied RNA their whole careers. Agris became intrigued with RNA in graduate school. Others, such as biology professor Ben Szaro, came to RNA late, by following a research question to its core.

Szaro studies how neurons send out projections in order to connect to other neurons. “When connections are lost between neurons, disease results,” he explains, naming neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Alzheimer’s. Focusing on neurofilament proteins, which provide structural support for neuronal projections, Szaro studies how nerves can regenerate. “We originally focused on proteins,” Szaro says. “Then we focused on DNA. Then we realized, nope! It’s the RNA that is the major central point by which the neurons decide how much protein to make.”

Birth of a New Institute

The story of the RNA Institute begins with a coincidence – a conglomeration of UAlbany and Capital District scientists whose research focused on RNA and who nurtured their shared interests through the Hudson Valley RNA Club. It continued with a strategic vision, a recognition that UAlbany could not compete against the country’s top research universities in genomics and proteomics.

Lynn Videka, then UAlbany’s vice president for Research, saw that by fully engaging this RNA research, the University could get ahead of the game. A senior scientist was needed to provide leadership.

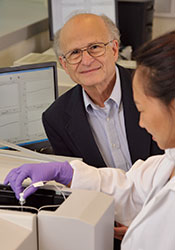

RNA Institute Director Paul Agris looks on as biochemistry student Seoyeon Hong works on a UV-visible spectrophotometer.

Enter Agris, who had spent years at North Carolina State University as researcher, professor and department chair. There, he formed the RNA Society, which brought together Research Triangle Park scientists to share data and methods. But his efforts to establish a formal RNA center never gained traction.

Former Duke postdoctoral fellow Scott Tenenbaum, now at the College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, called Agris to come take a look at UAlbany. Agris took up the challenge and, in 2009, started working on formalizing the RNA Institute, hammering out new faculty lines and new facilities while still doing research at NC State. He moved to UAlbany full time in 2010. At that time, senior faculty slots were filled first by Fabris and later by Marlene Belfort, who was previously at the Wadsworth Center of the New York State Department of Health.

Since then, two new junior faculty have been hired, and two more are on their way. “We’re using the institute as a way to recruit great faculty,” Agris says, adding, “The institute wouldn’t be here without the desire of UAlbany faculty in the first place.”

Research and Applications

How niche is RNA research? It’s not exactly a poor stepchild to genetics and protein research: Indeed, researchers in the field have been the recipients of more than 30 Nobel Prizes, eight of them since 2006. Still, with perhaps one exception, it’s been largely limited to very basic research in cell biology. Viewing RNA as a road to therapeutics has been slower to catch on. That one exception is the potential of a type of RNA that silences, or turns off, genes.

Student Yik Siu works in the Mass Spectrometry Center Lab.

“Two-thirds of the research in my lab is disease-oriented,” Agris says, and includes rare and neglected diseases, such as multi-drug-resistant infections. Agris has identified a bacterial RNA target for novel antibiotic drugs, which would be effective in treating drug-resistant infections that confound current antibiotic arsenals, such as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and methicillin-resistant staph infections (MRSA).

The vast majority of pharmaceuticals on the market are designed to target proteins in the body. Take, for instance, the top two prescribed drugs of 2010: Hydrocodone binds to neuronal proteins that dampen pain signals, and lisinopril binds to an enzyme in blood vessels to lower blood pressure.

Fabris says RNA has the potential to be a much more efficient target for therapies. Here’s why: To provide enough drug to interact with most copies of a particular protein, the dose is often high enough to produce other effects – including toxic side effects – on the body. But a single strand of RNA can code lots of the same protein, so in theory one might get more effect with lower doses. It’s comparable to shutting down production of widgets at the factory, rather than trying to track down and pull the product from store shelves later.

Innovation Rules

Making RNA the focus of an institute is novel in itself – and UAlbany covers the spectrum, from biophysics of the molecules to cellular functions. The RNA Institute has proved innovative in other ways, too.

The research facilities, located in the Life Sciences Research Building, include specialized laboratory spaces, such as an advanced computational center and an advanced instrumentation lab. Agris is adamant that these facilities are of a programmatic nature, much more than “core facilities,” because they also house potential collaborators for anyone investigating RNA. “They’re not just instruments, but staff people, too,” he says. “Thus, the institute engages in full-fledged, long-term collaboration with investigators on papers and on grant proposals. It is also a necessity to make the institute economically sustainable.”

Counterclockwise from top right, Fabris and Agris pose with graduate student Rebecca Rose; Siu; Hong; and postdoctoral fellow Kimberly Harris.

Another way the RNA Institute distinguishes itself is through its commitment to undergraduate research. No lip service here: The institute supports graduate students’ and postdoctoral fellows’ travel to present at national and international meetings. Individual faculty members financially support undergraduate research in the labs.

Seoyeon Hong, a biochemistry major, learned about research opportunities from a friend and, after working about 10 hours per week, for credit, during her junior year, spent her summer in the Agris lab. The work sharply contrasts with her coursework experience, where she followed standard written protocols to obtain expected data. Doing real research in a real lab is beyond what’s in a textbook, she says. “We sometimes get data we can’t explain.”

When that happens, Hong consults with Agris or postdoctoral fellow Kimberly Harris to troubleshoot. Or she combs through the scientific literature for alternative methods or interpretations.

Hong is undecided about her future, but continuing research science is an option she’s considering.

Agris, too, got his start as an undergrad. “I came out of that experience motivated to look for things that were new – not just what everyone else is doing.”

You know what he found: RNA.

- UAlbany Magazine

Fall 2013 - Cover Story

- Features

- Departments

- The Carillon

- Past Issues