Within Our Gates.

Within Our Gates then proceeds along a second storyline, a lengthy flashback that involves Alma Prichard, Sylvia's Northern cousin—who was once secretly in love with Sylvia's fiancé, Conrad Drebert. Alma, who orchestrated Sylvia and Conrad's estrangement, has undergone a transformation and now regrets her previous actions. In a conversation with Dr. Vivian, Alma reveals Sylvia's tragic past. The stark cinematic portrayal of the destruction of Sylvia's family allows Micheaux to address one of the most volatile and controversial topics of his era: Negro lynching. This segment of the film is also the most action-packed and racially confrontational.

|

Jasper works the land of Philip Gridlestone. Described as a "modern Nero, feared by the Negroes [and] envied and hated by the white farmers," Gridlestone has been stealing from his sharecroppers for years. Their lack of education has allowed him to juggle the books to his financial advantage. Gridlestone is assisted by Efrem, his gossipy servant, who—in many ways—is the most despicable of the African American male characters in Micheaux's film. He is an "incorrigible" tattletale, one who frequently drinks his "master's" liquor, and whose only "pleasure was to take from one place to another" any gossip he can obtain.

Determined to stop Gridlestone's exploitation of her father, Sylvia carefully manages his accounts so that he can settle without argument. That afternoon, Jasper enters the back of Gridlestone's house and goes into his office. Gridlestone looks upon Jasper with disgust while Efrem, his servant, is snooping outside a window. Gridlestone warns Jasper, "You're getting mighty smart, eh. I'm on to you. And remember the white man makes the law in this country." At this point a poor white man comes to a second window, on the other side of the office, with a gun. The title reads: "Yes, Gridlestone has cheated him also and when he called him to terms had laughed in his face, calling him Poor White Trash—and no better than a Negro"

|

Efrem gleefully rushes to spread the news, going to all of the white shops in town explaining that Jasper has killed Mastah Gridlestone. Here, as the film notes, he lives up to his reputation as the white man's friend. White men start to gather on the city sidewalks to discuss the matter. Landry gets his family, their belongings, and his gun, and they run off to the swamps, attempting to escape through a terrific rainstorm. Mobs of white men and boys set out on foot to capture them. The manhunt continues for more than a week. Micheaux indicates repeatedly that this unthinking mob is comprised of poor white men. The real killer is accidentally killed by some of the searchers, a victim of circumstances. Meanwhile, Efrem is in his full glory: "Tain' no doubt 'bout it—da whi' folks love me," he says to himself. All around him though, white people are growing impatient. "Here I is 'mung da whit flk while dem other niggahs hide in da woods," he thinks. Suddenly Efrem looks around nervously. "While we's wait'n what ya say we grab this boy," says one of the white men, referring to Efrem. "But you know me mastah John—I's the one who tells you." Efrem's pleas goes unheeded. He is dragged away—and lynched.

|

The same newspaper account gives a distorted view of the scene between Landry and Gridlestone. Reenacting the false newspaper account, Landry is shown chasing Gridlestone around the room while the white man, wounded, begs him for mercy. He falls to the ground and then the "savage Negro" beats him. Micheaux intricately demonstrates how the press, the legal system, and those in economic power worked together to oppress black men. He also illustrates how the lynching of black men had become part of consumer culture, a spectacle to be regarded as entertainment, news, and racial justification for violence by the white public.

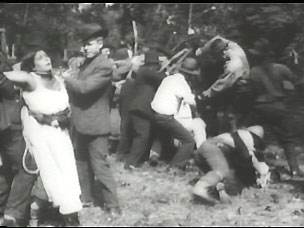

Jasper Landry, his wife, and son are finally captured. The "Committee," a white vigilante group, march the family to their place of execution on Sunday, the Lord's day. With clubs in their hands, the barbaric mob takes Mrs. Landry and beats her, while one man strips off her dress. Landry tries to choke the white man who humiliates his wife. What follows is a superbly chilling succession of shots in which Micheaux shows the fate of the Landry family. A shot-by-shot analysis is necessary to demonstrate the unsettling artistry which Micheaux uses to shock his audience.

- Shot 1 shows a lynching rope swinging in the breeze.

- Shot 2 depicts Mrs. Landry grabbing her ten-year-old son, Emil, trying to protect him.

- Shot 3, a remarkable indictment of the travesty of Southern justice, follows the mob forcing a noose around the boy's neck.

- Shot 4 shows a noose being placed around Jasper Landry's neck.

- Shot 5 shows the boy running away as the mob prepares to kill his father. The men shoot at Emil and he falls to the ground.[20]

- Shot 6 reveals that the boy has faked his death. He runs away and steals a horse while the crowd continues to shoot him.

- Shot 7 shows both husband and wife with ropes around their necks.

- Shot 8 displays the white men pulling the ropes.

|

|

The murder of the Landry family.

From Within Our Gates. |

The final shot shows these same men placing kindling around the lynching posts.

|

Micheaux then crosscuts the film, alternating the lynching scene with an attempted rape of Sylvia. She is trapped in a house with Armand Gridlestone, Philip's brother. A title reads: "Still not satisfied with the poor victims burned in the bonfire, Gridlestone goes looking for Sylvia." Micheaux interweaves scenes of the demise of the Landry family with the molestation of Sylvia, implying they are happening at the same time. The scenes read as follows:

- Scene 1 - Gridlestone chases Sylvia around the room

- Scene 2 - The mob cuts down the lynching ropes.

- Scene 3 - Gridlestone rips off Sylvia's coat.

- Scene 4 - The mob starts burning the lynched bodies.

- Scene 5 - Sylvia grabs a knife and fights for her life.

- Scene 6 - A huge burning bonfire in the night consumes the Landry's remains.

- Scene 7 - Sylvia gives up after a long and frantic fight.

|

|

Armand Gridlestone attempts to rape |

Cinema scholar Jane Gaines has proposed that the utilization of cross-cutting techniques in the melodramatic form has special meaning for the disenfranchised spectator because of the way the device is used to inscribe power relations. The lynching of the Landry family and the near rape of Sylvia placed the contemporary African American spectators in a totally hopeless position, made all the more painful because of their awareness that such things happened in the real world. Gaines also argues that this editing technique empowers minority spectators by awarding them moral superiority, demonstrating that they recognize the injustice and cruelty evident on the screen.[23] This dramatic scene has a structure remarkably similar to the climax of Griffith's The Birth of a Nation. While Micheaux never publicly commented on The Birth of a Nation, structural and thematic parallels are evident. In The Birth of a Nation it is a mob of black soldiers that threatens the white protagonists, with whom the audience is supposed to identify. In Within Our Gates it is a lynch mob of whites that threatens the major black figures.

While viewers are limited by the cinematic text on the screen, they are in the privileged position of being able to accept, negate, or reject the narrative of the film and its portrayal of power. Black British cultural theorist Stuart Hall emphasizes the relationship between the "encoding" function of the filmmaker and the "decoding" function of the spectator. He writes that "the relationship between the ideology contained within texts and the various ways in which individuals 'decode' or interpret that ideology is based on their own social positioning."[24] Thus, an African American spectator in 1920 was likely to reject the ideological underpinnings of The Birth of a Nation and accept the social message of Within Our Gates.

|

How can the viewer explain this reversal of political attitudes, in which Micheaux apparently overlooks the injustices he has so clearly laid out in the course of the film? He may have been an apologist for white America; certainly there are passages within his novels which would be considered racially offensive today. Micheaux claims in his novel The Homesteader, "Some of the race [African American] are very ignorant and vicious."[25] He may have been expressing a middle-class African American consciousness not atypical of the black intelligentsia of his day. He certainly believed that only a minority of African Americans were practical, responsible, and moral while the rest were impractical, immoral, and immature; he ignored the realities of poor black Southerners.[26] Micheaux may well have shared certain values and sentiments with a number of artists and intellectuals associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Alain Locke, professor of philosophy at Howard University and spokesman for the Harlem Renaissance, declared in 1927, " I would so much prefer to see the black masses going gradually forward under the leadership of a recognized and representative and responsible elite than see a frustrated group of malcontents later hurl these masses at society in doubtful but desperate strife."[27] Members of the Talented Tenth often had contempt for poorer African Americans, particularly new migrants from the South. They saw themselves as leaders of the New Negro movement. Micheaux and Locke both believed that their examples and those illustrated in their art should serve as inspiration for those in their race, particularly the masses.

But the question remains. Why would Micheaux choose to be so painfully provocative, to provide such a frank discussion of racial divisions in American society, only to cloak racial injustice with patriotism and victory in war? The Chicago Board of Censors, one of a multitude of state and municipal motion-picture censorship boards that were operating at the time, initially turned down Within Our Gates for its graphic display of lynching. Other filmmakers would have encountered censorship problems with the same material. Well known for editing and then re-inserting scenes in his films to circumvent the censors, Micheaux may have added the final scene in the film to address the objections of the censors.

There may have been another reason for this final scene. Produced during the "Red Summer" of 1919, Within Our Gates was a powerful indictment of the immense racial tension that existed in the postwar era. The epilogue may have been a call for peace and an end to violence, of which African Americans were the principal victims. In Chicago, where the film premiered, a terrible race riot had occurred the previous summer. Between April and October of 1919, over twenty-five race riots had taken place in towns and cities across the United States, in the South and North. Many whites living in Northern cities resented burgeoning black communities. As Micheaux accurately accounts in his opening title, racial violence was no longer unique to the South.[28]

|

|

So what does this have to do with Micheaux's "manhood" and his portrayal of African American masculinity on the screen? Micheaux, quite simply, put his manhood on the line by even making such a film. He admitted to the Omaha Nebraska Daily that the film was "bit radical." He released the film in the same week that the NAACP announced that at least nine African American veterans had been lynched in 1919, many while still in uniform. This was a bold move.[30] If one equates "manhood" with the stereotypical virtues of courage and daring, than the production of such a racially antagonistic film in early 1920 demonstrates Micheaux "acting" like a man.

Within Our Gates is also significant for the diversity of African American men that Micheaux portrays on the screen. Dr. Vivian and Conrad Drebert (Sylvia's first love) fit the mold of standard Micheaux heroic figures—light-skinned, muscular, paternalistic, well-educated, professional and concerned for their race. Charlene Regester has shown that African American standards of beauty for men in the post-World War I period often followed European standards.[31]. But Micheaux also included examples of black manhood that were more representative of the people in his audience. Certainly Jasper Landry and the unnamed sharecropper (both dark-skinned) are atypical characters in the repertoire of African American filmmaking of the period. Urban African American men at the time may have been portrayed as corrupt, or at least open to the vices of the wicked city, but at least they were urbane and worldly. In the standard black-directed film of the silent era, the poor rural African American sharecropper was usually seen as an uneducated country rube, a man who simply tried to live from day to day with little concern for the future. Micheaux's two farmers are quite the opposite. Realizing the value of education for their children, disciplined and hard-working, these men are willing to make sacrifices for the future of their family.

Micheaux includes three negative portrayals of black manhood in Within Our Gates - Larry (Alma's brother), Old Ned, and Efrem. He does not depict them simply as "bad," but uses each character to impart a particular lesson. Larry, an urban con-man, chooses crime rather than work and is willing to exploit members of his own race to meet his needs. He discovers that crime simply does not pay and his eventual fate is death. Old Ned, the preacher, is a tortured man. Ready to bend to traditional Christian practices in order "to get him a bit of the pottage," Old Ned is also aware of the results of his actions. A tragic figure, he represented the humiliation that black men endured when they stooped for the white man and "yes sahed" their way into submission. Efrem is a variation of the Uncle Tom character. More dangerous than Old Ned, Efrem is ready to sacrifice members of his own race in order to gain acceptance from the white community. Efrem is devoid of racial loyalty and eventually becomes the victim of his own displaced allegiances. Committed to the white man, he finds the commitment is not mutual. The terror in his eyes is evident when he realizes he will be the next black male victim to be sacrificed at the altar of white male barbarism.

|

- Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture

of Segregation in the South, 1890-1940 (New York: Pantheon Books,

1998), 199-240. [Return]

- One can only imagine the horror of African American audiences watching this scene. [Return]

- Chicago Defender (January 10, 1920), 6. [Return]

- Hale, Making Whiteness, 204. [Return]

- Jane Gaines, "Race, Melodrama and Oscar Micheaux" in Black American Cinema, Ed. Manthia Diawara (New York: Routledge, 1993), 57. [Return]

- Hale, Making Whiteness, 17. [Return]

- Micheaux, "The Homesteader," 59. [Return]

- Joseph A. Young, Black Novelist As White Racist: The Myth of Black Inferiority in the Novels of Oscar Micheaux (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989), 26. [Return]

- Alain Locke, "High Cost of Prejudice," Forum 78 (October 1927), 510. [Return]

- Tuttle, Race Riot, 14-15. [Return]

- Young, Black Novelist As White Racist, 139-141. [Return]

- Chicago Defender (January 3, 1920), 1. [Return]

- Charlene Regester, "Oscar Micheaux's Multifaceted Portrayals of the African- American Male: The Good, The Bad and the Ugly" in Me Jane: Masculinity, Movies and Women, Eds. Pat Kirkhamt and Janet Thumin (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1995), 175. [Return]

- One can only imagine the horror of African American audiences watching this scene. [Return]

|

World Wide Web links of interest related to Oscar Micheaux:

http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/MRC/Micheauxbib.html.

http://www.shorock.com/arts/micheaux/.

http://www.mdle.com/ClassicFilms/SpecialFeature/feb597.htm.

|

Copyright © 2000, 2001 by The Journal for MultiMedia History

Comments | JMMH Contents