FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

(American, 1951, 105 minutes, color, 35mm)

Directed by John Huston

Cast:

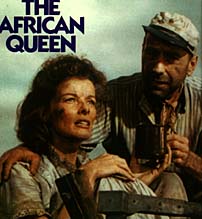

Humphrey Bogart . . . . Charlie Allnut

Katharine Hepburn . . . Rose Sayer

Robert Morley . . . . . . Reverend Samuel Sayer

Peter Bull . . . . . . . . . . Captain of Louisa

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

The story of Charlie Allnut and Rose Sayer appealed to John Huston instantly. C. S. Forester’s tale of a mismatched couple, the convict and the missionary lady, centered on one of the best colorfully conflicted duos in Huston films. The leads were first to have been played by Charles Laughton and his wife, Elsa Lanchester, and then by Bette Davis and David Niven. But Katherine Hepburn, then finishing a national tour of As You Like It for the Theatre Guild, loved the book, and saw in Rosie a woman much like herself—a prim-seeming product of a starched society with vast, hidden reserves of unorthodoxy and bravery. She’d never met Humphrey Bogart or director John Huston, but she admired both of them. She agreed to do the film on one condition—that the film would actually be shot in its setting, equatorial Africa. Renegade independent producer Sam Spiegel knew that Hepburn was the only Rosie in the world, and he gulped and agreed. No one could have known the agonies that awaited them, agonies that made everyone feel remarkably close to the world of Rosie and Charlie.

Shipping a whole movie company thousands of miles across the world and into the African bush greatly appealed to director Huston, who, after the experience of THE TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE’s Mexican locations, was even more eager to use extensive location work in this film. He flew over 25,000 miles of African terrain before choosing a camp near Biondo, on the Ruiki River in what was then the Belgian Congo. Not only did the realism of the African location for this particular story appeal to Huston, but so did the end-of-the world feel:

"I come from a frontier background. My people were that. And I always feel constrained in the presence of too many rules, severe rules; they distress me. I like the sense of freedom. I don't particularly seek that ultimate freedom of the anarchist, but I'm impatient of rules that result from prejudice."

Throughout his life, Huston took any excuse to light out for the territories. The god-forsaken Congo was the perfect place to make a film about how quickly the cheap paint of civilization can wear off the human psyche. For the rest of THE AFRICAN QUEEN cast and crew, it was a green hell. Spiegel had gone deeply in hock to make the film with the cast he wanted, and there was precious little left over for a huge location crew. For a time, Hepburn doubled as the wardrobe mistress. Missing from the African set were the squadrons of grips, gophers, and hangers-on common to a Hollywood shoot. In their place were bemused natives, lumber camp laborers, and the occasional colonial administrator.

"Nature," says Hepburn’s Rose Sayer in the film, "is what we were put on earth to rise above." But THE AFRICAN QUEEN group kept most intimate company with nature for the long weeks on African location, close by the black water of the Riuki in the rainy season. The cast endured blood flukes, crocodiles, huge army ants, wild boars, elephant stampedes, malaria and dysentery. Poisonous snakes in the outhouses and bugs in the food added even more character to the steaming inferno, and Hepburn lost twenty pounds making the film. Sanitation was nonexistent, a particular horror for Hepburn, fastidious to a fault and a urologist’s daughter.

Bogart and Huston took to consuming Homeric amounts of alcohol, as the jungle closed in about them. Bogart’s own self-reliance and confidence initially made him despise the chinless Charlie Allnut. But the weeks in the jungle worked a change on Bogart, as he sampled the destitute life of Charlie. As Huston said, "All at once he got under the skin of that wretched, sleazy, absurd, brave little man."

Hepburn became angry with Huston and Bogart, and berated them for their endless practical jokes at her expense, including obscenities written in soap on her mirror. "She thought we were rascals, scamps, and rogues," said Huston, with a smile, many years later. Of course, she was right. "But eventually she saw through our antics and learned to trust us as friends." Hepburn developed a respect for Huston as a true ‘actor’s director,’ who gave her the key to Rose Sayer when he advised her to play the role like Eleanor Roosevelt. "That is the goddamnedest best piece of direction I have ever heard," wrote Hepburn, and their friendship was sealed.

For Hepburn, the role of Rose, "the skinny, psalm-singing old maid" who discovers a reservoir of strength and very earthly affection for one completely unlike herself, was art imitating life, complete with tsetse fly bites and leech infestations. She came to regard the shoot as one of the great adventures of her life, immortalizing it in a 1987 book with the absolutely accurate title The Making of The African Queen or How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind.

The AFRICAN QUEEN shoot, like the search for Scarlet O’Hara, or Darryl F. Zanuck chasing starlets around his desk, is now part of Hollywood lore. Clint Eastwood’s 1990 film WHITE HUNTER, BLACK HEART is loosely based on the Huston of THE AFRICAN QUEEN, from a novel by Peter Viertel, one of THE AFRICAN QUEEN’s screenwriters. THE AFRICAN QUEEN shoot turned out to be a truly Hemingwayesque experience for the Bogarts, Huston, and Katherine Hepburn, perhaps "The Short, Happy Life of Francis Macomber" mixed with an equal measure of The Green Hills of Africa. But not really, for THE AFRICAN QUEEN affirms the primacy of romance and trust over the worst obstacles of nature and human nature. Hepburn captured the essential joy of THE AFRICAN QUEEN in a mental snapshot from the film: "Dear Bogie. I'll never forget that close-up of him after he kisses Rosie, then goes around in back of the tank and considers what has happened. His expression—the wonder of it all—life."

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

The African Queen

The African Queen