FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

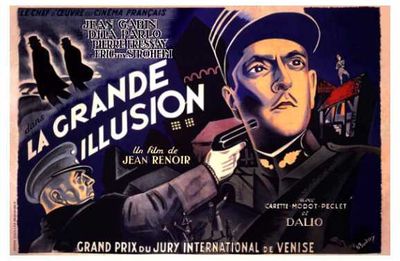

The Grand Illusion [La Grande Illusion]

The Grand Illusion [La Grande Illusion]

Directed by Jean Renoir

In French with English subtitles

(France, 1937, 114 minutes, b&w, 35mm)

Cast:

Jean Gabin……….Lt. Maréchal

Dita Parlo……….Elsa

Pierre Fresnay……….Capt. de Boeldieu

Erich von Stroheim………..Capt. von Rauffenstein

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

It is a film of surpassing melancholy, this tragic chamber drama of prison camp life and death in World War I. Released in 1938, with the world once again at war's edge, The Grand Illusion was a quiet plea to a self-destructive Europe not to commit suicide again. Europe did not listen. Two French flyers, de Boeldieu and Maréchal have been downed. They are ushered into the mess of the German squadron responsible for shooting them down, where they are toasted by the aristocratic ace, von Rauffenstein, in an episode taken intact from the archaic courtliness of the air war that so contrasted with the anonymous slaughter of the trenches below. De Boeldieu and Maréchal find themselves in a prison camp, deep within German lines, presided over by a now-badly injured von Rauffenstein. The comradeship he had once felt for them remains, now filtered through his regretful responsibilities as commandant. The French have a duty to escape, and von Rauffenstein has a duty to kill them when they try.

Director Jean Renoir was a veteran of the First World War, first as a cavalryman, then as a pilot. He based his film on conversations he had with POWs, German and French; many of the incidents in the film come from these discussions with men who had been behind the wire during the war, sometimes for years. But in light of the German reoccupation of the Rhineland in 1936, the bloody obscenity of the Spanish Civil War, and German intimidation on every hand, the project seemed a fearfully ill-advised one, and backers could not be found. Only the promise of Renoir's great friend, star Jean Gabin, to appear in the film, broke the dam and got the money flowing. (Gabin was no philanthropist; he undoubtedly recognized in Renoir his muse as an actor, for his films with Renoir, including The Grand Illusion, Le Bete Humaine, and The Lower Depths, are among this actor's greatest work.) Renoir's affinity for the sad-eyed Gabin is evident, and that is Renoir's old pilot's tunic that Gabin is wearing. Meanwhile, von Rauffenstein's uniform is far more elaborate, said Renoir, than one typically worn by a prison camp officer, reflecting the officer's princely view of himself, and heightening the irony of being stuck in one of the war's backwaters, like a peacock in a swamp. The film turned out to be a reunion between old combatants off the set, as well as in the story, for the technical advisor on the film, Carl Koch, had been a German anti-aircraft gunner in the same sector where Renoir had flown in a reconnaissance squadron in 1916.

Erich von Stroheim's von Rauffenstein is the conflicted, war-weary pivot around which the film's fatalistic story turns. Initially, the part was to be a small one, but an executive on the film's staff met von Stroheim at a cocktail party, and on the spur of the moment, signed him to the film, and immediately, the part was expanded for von Stroheim's prodigious, baroque talents. Renoir was overwhelmed at his good luck, for, as one of Renoir's colleagues said later, "von Stroheim was a kind of God to him." It had been the films of von Stroheim the director, like Blind Husbands and Greed, that made Renoir aware of the naturalistic possibilities of the medium. Renoir was so excited that he immediately began inventing and shooting scenes with Stroheim that were not intended to be part of the film, just to have the precious experience of working with the actor. (The Vienna-born Jewish actor could not, by the way, speak German very well; he learned his lines phonetically.) It was von Stroheim's idea to put von Rauffenstein in the back brace which makes him, literally, arch; von Rauffenstein's frustration, both at being away from the front lines and from being forced to fatally discipline men whom he respects is now made visible, in one of the great costuming choices in the history of the movies.

Years later, Renoir said that the three films beginning with The Grand Illusion (next came La Marseillaise and The Human Beast) were made without flashy technical work, to allow audiences to concentrate on the story. "The only innovation," he wrote, "is on the style of the actors… in pushing further.. a certain kind of semi-improvisation." Indeed, the dialogue in some scenes among Stroheim, Gabin, and Pierre Fresnay were improvised, and the empathetic, almost loving looks that sometimes pass between the men speak of relationships very deeply felt. But Renoir's cinematography here is exquisitely dramatic, the camera slowly and methodically probing the spaces and souls of the prisoners.

The film was instantly lauded by everyone except the Fascists, whether of Germany, Italy, or France. The Germans pressured the Italians to avoid giving the film a prize at the Venice film festival, and then released it themselves in Germany, minus reference to the character Rosenthal, a Jew. The film was well liked by Hermann Goering, an old fighter pilot himself, for evoking the camaraderie of the knights of the air. Freedom-loving people, however, found in the film a powerful indictment not only of war, but of the class system, as well. In the U.S., one of its partisans was Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the film ran for months in New York City after winning a special award at the 1939 New York World's Fair. A worldwide hit of its day, the film was still playing in several countries when war broke out in September, 1939. In the confusion of wartime Europe, several versions of the film circulated, many with cuts mandated by local censors. It was not clear the film would ever resurface in its complete form. This is one of the cinema's great tales of humanity struggling to speak in universal tones. The language of nationalism has obviously failed these characters; perhaps, says Renoir, only the language of art, of cinema, is left for all of desperate humankind to share. The coming war would shortly close in on Renoir, and on all of French cinema. Renoir and Gabin would make their way to the U.S., where each worked in Hollywood during the war, Gabin returning to fight the Germans in North Africa and Europe, winning the Croix de Guerre and the Medaille Militaire in Charles DeGaulle's Free French Army. Each went on to become widely regarded as, respectively, the greatest director and greatest actor that the French cinema has ever produced, a critical estimation unimaginable without the majestic accomplishment of The Grand Illusion. The film survived the war intact: a complete negative was stored by the Nazis, and found in Munich after the war by American occupation authorities. The poetic realism of The Grand Illusion outlasted the savage conflict that had once engulfed it; now, it lives again, perpetually new in its passion and yet saddened by its own knowledge of the violent absurdity of war.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.