FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

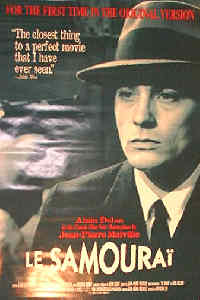

Le Samourai (The Godson)

Le Samourai (The Godson)

(French, 1967, 101 minutes, b&w, 35mm)

Directed by Jean-Pierre Melville

In French with English subtitles

Cast:

Alain Delon . . . . . . . . . . Jef Costello

François Périer . . . . . . . . . .The Superintendent

Nathalie Delon . . . . . . . . . . Jane Lagrange

Cathy Rosier . . . . . . . . . .Valerie

Jacques Leroy . . . . . . . . . . Gunman

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

"At birth man is offered only one choice—the choice of his death. But if this choice is governed by distaste for his own existence, his life will never have been more than meaningless." — J-P Melville

As the release of the restored version of his classic LE SAMOURAÏ impends, it’s a good time to look back at the varied ouevre of the sui generis Jean-Pierre Melville, 1917-1973. Father of the Nouvelle Vague, precursor of Bresson, interpretor of Cocteau, master of the French crime/gangster genre, Jean-Pierre Grumbach (self-renamed after his favorite author) remained always separate and himself. Mad about American movies from an earlier age, he differed from his New Wave admirers (some of whom he dismissed as "amateurs") in originally having a life outside cinema, serving in the Army and then the Resistance throughout the war; then redefining the term independent with his early self-financed-on-the-proverbial-shoestring adaptations of Vercors and Cocteau (in the first case, LE SILENCE DE LA MER, without even securing the rights); and, eventually moving to those austere, if star-stunned, evocations of a fantasy underworld ("The real inhabitants of the milieu don’t interest me."— J-P M) in which men, no matter how criminal, still lived by their own personal codes. —National Film Theatre, Washington, D.C.

It is a gray, grim little room, as barren as the life of the man who inhabits it. A man reclines on a bed, still and silent. Smoke curls from his cigarette. It is raining, and the monotonous hush of passing traffic is all we hear. That, and the chirping of a little bird in a cage.

This is the world of "Jeff Costello" (Alain Delon) the expressionless assassin whose gun is quick and whose footfalls are soft. He is entirely focussed on the job at hand, in this case, the killing of a night club owner. It is a contract arranged by an unseen, unknown client. Director Jean-Pierre Melville begins the film by showing us the anatomy of this hit in understated cinematic language. Jeff recoils from the expression of emotion, and it is as if the film follows his lead. LE SAMOURAÏ’s use of camerawork and editing is economical, even spare. But he is soon intrigued by "Valerie" (Cathy Rosier), a lovely black pianist at the club. She is a witness—or is she?

Melville sets up an elaborate backstory: the killer is said to be fascinated by the Japanese warrior tradition of bushido. While Melville was deeply influenced by the revision of the samurai film undertaken by Akira Kurosawa, the reference to bushido may be a dodge. In fact, Melville has invented the "Book of Bushido" that Jeff Costello reads like a holy text. Jeff’s idols are cinematic ones, whether he (or Melville) admits it or not. Delon’s character seems a Gallic riff on Alan Ladd’s baby-faced killer of THIS GUN FOR HIRE, and there are any number of other homages to film noir, always retooled in a way that renders them distant and strange—never really romantic. There are other influences that circulate throughout Melville’s brittle little film, including that of Jean Cocteau’s version of the Orpheus story. Here, the pianist Valerie becomes a dangerous obsession for the otherwise cautious Jeff. (Melville had worked with Cocteau.) But Melville’s first loyalty is to the order of the trench coat, the .45, the fedora, and the Lucky Strike.

LE SAMOURAÏ helped to bridge the years between TOUCH OF EVIL (1958, Orson Welles) and CHINATOWN (1974, Roman Polanski). These were the years in which film noir fell into disuse among American directors, but they were also the years when passion for the great sardonic masterpieces of the genre—THE ASPHALT JUNGLE (1950, John Huston), UNDERWORLD U.S.A. (1994, Luc Besson), KISS ME DEADLY (1955, Robert Aldrich)—burned brightest among French and American critics. There were a few other films, like Stephen Frears’ GUMSHOE (1972), Francois Truffaut’s THE BRIDE WORE BLACK (1967) and Alain Corneau’s SÉRIE NOIRE (1979) that came out of Europe in that interregnum, but few were as faithful to their cinematic ancestors as LE SAMOURAÏ.

Melville’s respect for his loner hero may well come from his own backstory. Resolutely against the restrictions that went with France’s studio system, he filmed his first feature, LE SILENCE DE LA MER in 1949 without help from industry, sneaking his shots where he could, inventing financing as he went. Until 1967, he had his own tiny studio, Jenner, where he worked without interference or compromise. When circumstances forced him to produce and distribute his films through more conventional channels, he retained his reputation for iconoclasm. He appears in a cameo in Jean-Luc Godard’s BREATHLESS (1959), a tip of the hat from one anarchistic personality to another.

Like "Leon," the ascetic hitman played by Jean Reno in THE PROFESSIONAL (1961, Samuel Fulles) who is only one of Jeff Costello’s heirs, LE SAMOURAÏ, the film, is uncompromising in its style, deadly in its menace, and impossible to turn away from.

Selected Filmography (all director/screenwriter)

1972—Un Flic, aka Dirty Money

1966—Le Deuxième Souffle, aka Second Wind

1961—Le Doulos, aka Fingerman

1961—Leon Morin, Prêtre, aka The Forgiven Sinner

1955—Bob Le Flambeur, aka Bob the Gambler

1950—Les Enfants Terribles, aka Strange Ones

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.