FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

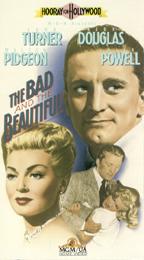

The Bad and the Beautiful

The Bad and the Beautiful

(American, 1952, 118 minutes, black & white, 35 mm)

Directed by Vincent Minelli

Lana Turner . . . . . . . . . . Georgia Lorrison

Kirk Douglas . . . . . . . . . . Jonathan Shields

Walter Pigeon . . . . . . . . . . Harry Pebbel

Dick Powell . . . . . . . . . . James Lee Bartlow

Gloria Grahame . . . . . . . . . . Rosemary Bartlow

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

Vincente Minnelli had been to Hollywood once, for Paramount, and it hadn't worked. Minnelli felt the film musical was a stagnant, cliche-ridden form, and he spent the better part of the 1930s revitalizing the musical on the New York stage. So when legendary producer Arthur Freed drafted him from Broadway in 1940, Freed made an unusual arrangement: Minnelli could come and simply observe things for a year with pay at the new MGM musical production outfit Freed was putting together with dancer Gene Kelly, composer Roger Edens, and choreographer Robert Alton. If Minnelli remained convinced that the screen musical was incapable of transformation to a high art, he could return to the main stage.

Minnelli agreed, and the months he spent observing the birth of the great Freed Unit at MGM formed the basis for his unique anthropological document of the dream factory, THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL. Minnelli's passion for making movies was kindled during this time, but so was his ability to view his cronies' (and his own) artistic and personal obsessions dispassionately, even clinically.

What the Hollywood Minnelli saw on this remarkable sabbatical was out of a script by Salvador Dali, a melange of truly surreal impressions. Some of these episodes revealed the immense imaginative power of the medium that Minnelli would soon command, such as the day on the STRIKE UP THE BAND set when Freed offhandedly asked him to come up with an idea for a production number, and Minnelli's gaze fell on a bowl of fruit. Instantly, the entire studio turned itself inside out to produce a number based on, well, uh . . . based on a bowl of fruit. At other times, what the Hollywood Minnelli saw from the sidelines was straight out of Nathaniel West's The Day of the Locust. There was for instance the day Minnelli was present at the very first audition of tiny child star Margaret O'Brien. Her agent brought the shy, quiet four-year-old into Freed's office and said, "All right Margaret, do something for Mr. Freed." Demure little Margaret went off like Mt. Vesuvius. She threw herself headlong at Freed, weeping and frantically tearing at his sleeves as she screamed, "Don't send my brother to the chair!!! Don't let him fry!!!" O'Brien was hired on the spot, of course, and Minnelli understood that a strange kind of history was being made in his presence.

Minnelli became fascinated with the creative paradox of Hollywood: it was a place where hypocrisy and deceit reigned, yet also a place where loyalties could run as deep as any he had ever seen. Minnelli saw front-office machinations worthy of Machiavelli, but he also saw intensely creative people exhaust themselves staying up night after night to help a colleague out of a jam. Sometimes, the same soundstages witnessed both the lies and the love, as productions became melodramas unto themselves. It was a paradox Minnelli came to love, one he memorialized in

several films such as THE BANDWAGON, TWO WEEKS IN ANOTHER TOWN and A MATTER OF TIME. As he mused in his autobiography I Remember it Well: "There were dark undercurrents to be sure . . . The talk of the dehumanizing of the stars and the prostituting of the writers' talents. But never had I met such animated robots or such willing whores." Or, as Minnelli's good friend Oscar Levant was wont to say, "Strip the phony tinsel off Hollywood and you'll find the real tinsel underneath."

THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL was first brought to Minnelli by producer John Houseman as a short story titled "Memorial to a Bad Man," but the new title perfectly miniaturized the Hollywood that sharpened the knife even as it kissed the cheeks. As he remembered it fondly:

It was a harsh and cynical story. All that one hated and loved about Hollywood was distilled in the screenplay . . . the ambition, the opportunism, and the power . . . The philosophy of 'get me a talented son-of-a-bitch.' But it also told of triumphs against great odds, and the respect people in the industry had for other talents.

For inspiration, Minnelli just looked around. The character of Jonathan Shields (Kirk Douglas) he based on the maddening, mercurial David Selznick, a genuinely creative man who inspired fierce loyalty and fierce hatred -- in the same people. He ruthlessly steals pictures from others, cruelly manipulates impressionable performers, and uses all who come within his grasp. Yet his exploitation hides a twisted affection and a wholesale devotion to moviemaking. The much-admired B movie producer Val Lewton appears as Harry Pebbel (Walter Pidgeon), while much of the character of Georgia Lorrison (Lana Turner) is based on the brief, tragic life of Diana Barrymore. A little of William Faulkner finds its way into Dick Powell's soft-edged portrayal of the Southern writer James Lee Bartlow, and Latin matinee idol and offscreen Lothario Gilbert Roland plays Latin matinee idol and offscreen Lothario "Gaucho Ribera." There are even catty references to the Von Stroheim/Von Sternberg martinet of Hollywood lore (Ivan Triesault as Von Ellstein), and the laconic Alfred Hitchcock (Leo G. Carroll, Hitchcock's favorite character actor, as Henry Whitfield).

Olde Hollywood was beginning to die a lingering death by the time THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL was made. It seemed a time for elegies; SINGIN' IN THE RAIN, A STAR IS BORN, and SUNSET BOULEVARD were all released within a few years of THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL. Minnelli's feeling for the industry he loved and hated was not backward-looking regret, but glorious intoxication, and THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL's sumptuous black-and-white photography by Robert Surtees catches the bouquet of that heady, sweet wine. Here is the empty studio at night, deserted and ghostly. Here are the jumbles of stock props and costumes, ready to incarnate a thousand wistful imaginings. And here are the actors, frail and silly and real. Minnelli's trademark boom camera swoops and dives into this world with total assurance, for it is more than just the world he lives in. Ultimately, it is a world he adores almost helplessly, for this is a charming decadence. A one-time MGM contract writer, F. Scott Fitzgerald, had written of a producer's screening room in his movie industry romance The Last Tycoon: "Dreams hung in fragments at the far end of the room, suffered analysis, passed -- to be dreamed in crowds or else discarded." THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL is deeply concerned with what Fitzgerald called "analysis," but what Minnelli understood as an exercise in mass psychoanalysis, a soul-torqueing attempt to match the creative artist's private desires and nightmares with the fears and longings of his audience, out there in the dark of the theater.

Others have called THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL a film noir, because of its dark flourishes of deceit and despair. In fact, it is an ironic paean to the industry it appears to scorn, an admission that, by 1952, Minnelli knew that he could never again renounce Hollywood's cheating ways or its manifold attractions. In THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL, Vincente Minnelli joyfully announced that he had found opera in a sausage factory.

Minnelli never lost the sense of abstraction and solitude he first found on his arrival in 1940, though his sets were always a marvelous whir of activity, and his films among the highest achievements of Hollywood as a collaborative process. "Though I was fascinated by the work at the studio, I had trouble becoming acclimated to the town itself. I'd made several friends, but I still felt isolated. It was a strange brand of loneliness . . . relentless and unrelieved . . . I'd leave the studio at dusk and look at the flatlands around me. In the distance stood a solitary oil well. I found the lonely silhouette rising out of the ground quite symbolic. . . . I sensed this indifference about the town. So many of us were alone in a crowd of impassive faces."

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.