![]()

Passing From Light Into Dark

John F. McClymer

[Note: This discussion began as a paper, co-authored with Charles W. Estus, Sr., for a conference at the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, in 1996. It grew out of our work, supported by a Public Programs grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, in curating an exhibition on "The Swedish Creation of an Ethnic Identity for Worcester, Massachusetts" at the Worcester Historical Museum. That paper looked at how Swedes appropriated other racial and ethnic identities as ways of affirming their own American and Swedish-American identity. In its present form, "Passing from Light into Dark" incorporates much of the evidence and argument of that early version but looks beyond Worcester and Swedes.

"Passing from Light into Dark" is a companion to a discussion of The KKK in the 1920s. Both deal with race, ethnicity, and nationality as foci of the "culture wars" of the 1920s. "The KKK in the 1920s" looks at politics, broadly defined. "Passing" looks at culture, defined equally broadly. Both argue that pre-emptive attempts to define who was or was not a real American, so characteristic of the years immediately following World War I, failed, despite such significant initial successes as Prohibition, immigration restriction, and the Red Scare. At the same time, racial boundaries held firm. The failure to limit "real" Americans to those of "Nordic" stock is of a piece with the success in excluding people of color.

In making this argument, I have taken issue with a number of historians from whom I have also learned much. I have decided to put the historiographical discussion into a separate appendix rather than carrying it on in footnotes, as is the more common practice. This is because of the extended nature of the discussion.

I would like to acknowledge the contributions of Charles Estus to this essay and also the suggestions of Lucia Knoles and Gerd Korman. All are friends as well as colleagues.]

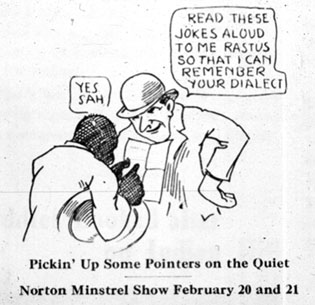

In 1917, just on the eve of the American entry into the war, the Norton Company of Worcester, Massachusetts, the largest manufacturer of industrial abrasives in the world, put on its annual Minstrel Show. The performers were Norton employees, many of them first and second-generation immigrants. Swedes formed by far the largest single group within the company's workforce. The show was part of the company's Americanization campaign, itself part of Norton's overall practice of welfare capitalism. Norton sponsored baseball, basketball, and other teams; it organized garden shows, an annual Folk Festival, employee picnics and outings; it provided company facilities for a camera club and for a pig club; it published a company newspaper, The Norton Spirit. It pioneered safety and industrial medicine measures. And it staged an annual Minstrel Show which involved scores of Norton workers as singers, dancers, and comedians. Others worked on sets and costumes, sold tickets, and did other tasks, such as publicity. [1]

Passing from Light into Dark

Source:"Passing from Light into Dark" was the caption of a cartoon in a special issue of the Spirit promoting the show. "Passing" normally referred to African Americans seeking to live as whites. It was, both in this sense and in the ironic sense intended by the Norton Spirit artist, a basic trope of American popular culture. "Showboat" is a prominent case in point. Universally acknowledged as the first great American musical, it fused story and music as it explored the meaning of race and racism. Central to the plot is the attempt of Julie, the "greatest leading lady on the river," to "pass." [2]

As the curtain rises, she is successful, happily married to a white man who knows her racial origins, and best friends with Magnolia, daughter of the showboat's owner, Cap'n Andy. But, a member of the crew learns her secret and threatens to reveal it unless she sleeps with him. She refuses, and he seeks out the local sheriff � the boat has stopped at a Mississippi town. Her husband finds a way of warding off charges of miscegenation; he pricks Julie's finger and then his own. They press their fingers together. When the sheriff arrives, he informs him that "I got nigger blood in me." "One drop of nigger blood makes you a nigger in Mississippi," the sheriff observes and then orders Cap'n Andy not to put on any shows with a racially mixed cast. Julie and Bill, her husband, leave the showboat. Magnolia, distraught at what has happened to her friend, tries to go with them. "Julie was my best friend" before the revelation of her African-American ancestry, Magnolia cries, "and she hasn't changed." "Of course she hasn't," Cap'n Andy agrees.

Jazz Singer Photo

Source:"Showboat" challenged all of the settled beliefs about race. Almost miraculously, it persuaded white audiences to empathize with Julie, to echo Magnolia's cry that Julie was still the same person she had always been, and to applaud Cap'n Andy's view that such a cry proved Magnolia was "a damn fine girl." Yet Julie's story ends unhappily. Alone, alcoholic, and in despair, she sees Magnolia years later in Chicago. She keeps her presence hidden but does Magnolia one last good turn by sacrificing her own chance at employment as a singer. Passing from dark into light ends in tragedy. This was the received wisdom of the day, and it provided the context within which all of the variations on passing from light into dark detailed here took place.

Minstrels Are We

What sort of Americanization effort was a minstrel show? Norton Company records explain. George N. Jeppson, son of one of the founding partners, had succeeded his father as Production Manager, and he spearheaded Norton's Americanization efforts. There were some within the Company, he wrote in a memo, who criticized the time and money devoted to these programs. They believed "that a fellow ought to work and choose his own recreation after work." That might be fine for "the Average American who is born here" but not for the "many young men who come here as immigrants and are away from a home or church influence." They needed the assistance of "their American-born fellow employees." They needed "to feel at home in their company." Then, but only then, would they be ready for formal instruction in English and Civics in "organizations like the YMCA." The Minstrel Show was a way of getting Swedish-born and other immigrants to rub elbows with their "American-born fellow employees," helping them "to feel at home in their company." Jeppson's father was himself an immigrant from Sweden.

Minstrel shows had toured the United States since the 1840s. They had lost some of their audience to vaudeville and then to the movies but remained popular as amateur productions. Church groups, fraternal organizations, companies like Norton, all continued to put them on. Further, elements of minstrelsy lived on in vaudeville and in movies. In "passing from light into dark," as a result, Norton employees participated in long-standing -- and ongoing -- American tradition. [3]

In 1917 The Norton Spirit published a special edition dedicated to the show. It both indicates the significance the company attached to the show and provides a wealth of detail. Here is the program. It included the expected, songs like "Carry Me Back to Old Virginia." But "Little Coal Black Rose" and the Plantation "Orchestra" shared the stage with Italian opera, a skit satirizing Norton Company policies and procedures, and a patriotic salute to U.S. troops stationed along the border with Mexico. The show closed with cast and audience joining in "The Star-Spangled Banner."

Acquiring "American" racial attitudes was clearly part of what coming to "feel at home" meant for Norton's immigrant employees. Acquiring a working knowledge of ethnic stereotypes was part too. Would Swedes have encountered a "pickaninny" like "Rose" without Company assistance? No doubt in time, but the Spirit special issue was a primer in American prejudice. In need of "fresh" material, a cartoon shows one of the prospective minstrels asking an acquaintance if he knew any new "Coon" jokes. "Pat" only knew Irish jokes. This was a Norton "in" joke since there were virtually no Irish employees in the company. Further, as all knew, given Swedish-Irish hostility in Worcester, an Irishman was about as likely to tell a Swede an "Irish" joke as "Rastus" was to coach a white man in his "dialect." But the cartoon had still another point. Change "Muldoon" to "Rastus," alter the brogue to a drawl, and you have all the "fresh" material needed. Irish jokes, unaltered, were common in Norton Company minstrel shows. In 1924, for example, Norton used Saint Patrick's Day as the theme. The resulting fusion of cork make-up and shamrocks that resulted suggests much about the relationships between acculturation and ethnicity. [4]

Doon and Rastus. Norton Company Mistrel Show.

Source: Norton Spirit, 1917.1924 in the public life of Worcester, Massachusetts, and in the rest of the United States

What did it mean to use St. Patrick's Day as the theme for the 1924 show? 1924 witnessed a battle for control of Worcester's streets between the Ku Klux Klan and its opponents, organized around the Knights of Columbus, an Irish-dominated Catholic fraternal order. By allowing first and second-generation Swedes to join in Worcester, something that did not happen elsewhere, the Worcester Klan explicitly affirmed that American nationality and ethnicity could reinforce one another. So did its arch antagonist, the Knights of Columbus, which regularly labeled the Klan unAmerican. [5]

The Klan had two centers of strength in the city -- Quinsigamond Village, Worcester's largest Swedish neighborhood, and Greendale, home of the Norton Company. The Village was so thoroughly dominated by Swedes that residents used to joke that one needed a passport to cross the bridge on Millbury Street which marked its entrance. The Village had half a dozen Swedish churches, all Protestant, and no Catholic churches. The Norton Company, also a Swedish bastion, sponsored a new club for its employees in 1924, the Ericson Lodge, named after the Swedish-American inventor whose Monitor duelled the Merrimack in the Civil War. The Lodge was a KKK klavern. Some of the Norton workers who "corked up" to "salute" St. Patrick's Day also donned white robes and hoods to protest the Irish influence in Worcester's politics and schools and to denounce their opposition to Prohibition.

It was highly unusual for immigrants to join the Klan. Indeed Klan regulations forbade it. Instead Klan organizers, aka kleagles, would create parallel organizations for Welsh or Scots-Irish or other immigrants who wished to join. The Worcester kleagle, however, opened the Klan to Swedish immigrants. Those who joined proclaimed their Americanism. So did those who attacked them. At the same time, Swedes who joined the Klan via the Ericson Lodge simultaneously proclaimed their ethnicity, as did those who opposed the KKK by joining the Knights of Columbus. In joining the Klan's "Fight for Americanism," in the words of Imperial Wizard Hiram Wesley Evans, as Swedes, the new Knights of the Invisible Empire were enacting a fusion of acculturation and ethnicity which is one of the central themes of this discussion. So too were the Irish Americans who opposed the "unAmerican" KKK by means of a Catholic fraternal order. Their dispute was over both the meaning of "Americanism" and over which ethnic groups were entitled to claim American nationality.

When KKK members in Worcester put on their robes, they became marked men, literally. Anti-klan activists often lay in ambush outside their gatherings. Those opposed to the Klan took down the license plate numbers of those attending; friendly police then supplied them with information about who owned the vehicles. This led to the creation of a listing of Klan members, to its publication, to boycotts of Klan-connected businesses, and to other forms of retaliation, some of them violent. [6]

In October, 1924 there was a Grand Konvocation held at the Agricultural Fair Grounds which adjoined the Norton Company. Thousands of new Knights assembled for a mass induction ceremony. After the meeting, as Klansmen and their families drove away from the Fair Grounds, an anti-Klan mob attacked. Young men jumped upon the running boards of cars, pulled occupants out of them, set some of the vehicles on fire, overturned others, and beat up whomever they got their hands on. Worcester police, most of them Irish, did what they could to prevent actual loss of life. One policeman on a motorcycle drove it into a small mob beating Klan members and rescued them. The police made few arrests, much to the indignation of Worcester's two Republican newspapers, both of which supported the Klan. Those few included several Klan members on weapon possession charges and one Irish-American teenager.

1924 also witnessed an epic struggle within the Democratic Party over the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan endorsed William Gibbs McAdoo, the frontrunner for the nomination. McAdoo was a Southerner by birth who had become a successful New York City lawyer and businessman. During World War I he had served as Secretary of the Treasury. He had also married Woodrow Wilson's daughter. He was Wilson's political heir. And that included Klan support. It was Wilson who agreed to have the initial showing of D.W. Griffith's "Birth of a Nation" at the White House and who endorsed its heroic portrait of the first Klan during Reconstruction. "It's like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all terribly true." McAdoo in 1924, for his part, issued a statement affirming his support of freedom of religion for all Americans. He did not repudiate the KKK' s endorsement, however. This led Oscar Underwood, Senator from Alabama, and Al Smith, Governor of New York, to challenge him for the nomination. Both denounced the Klan and urged the party to include a plank in its platform condemning it by name. Instead the party, led by the McAdoo supporters, rejected the plank by four votes. Party rules stipulated that a nominee gain two-thirds of the delegates' votes. The bitter division over the Klan showed that none of the leading candidates could muster that number. 102 ballots later there was still no nominee. Finally, exhausted delegates agreed upon John W. Davis of West Virginia. McAdoo's political star waned. So did Underwood's, and Davis's. Anti-Klan activists in Worcester and elsewhere found a champion in Smith. [7]

The Norton Company Minstrel Show, cont.

The 1917 Norton Company Minstrel Show presaged these antagonisms, and the reinforcing relationship between acculturation and ethnicity. Immigrant workers learned that one could "black up," that is, pass from light into dark, in a spirit of wholesome fun that the entire family would find amusing because white Americans knew that African-American speech and appearance were intrinsically comic. Note, for example, the way the Norton cartoonist made "Gilbert" and his cat share several facial features. The Irish jokes, told in the same make-up, demonstrate that learning how to "blacken" each other's reputation was another routine part of the acculturation process. The Irish, for their part, had learned this as well. They too put on minstrel shows, usually parish church productions, throughout the first decades of the twentieth century in which they routinely made sport of other ethnic groups. The front page of the [Worcester Catholic] Messenger for March 2, 1906, for example, told of the great success of the St. Anne's show in which "The German School" segment had followed the "Rufus Rastus Johnson Brown" and "Holy Cross 'Choo-choo'" numbers. The following year "the boys of St. John's Lyceum" put on, according to the Messenger, "probably the best amateur minstrel show chorus seen in Worcester in recent years." One of the highlights was John F. Putnam's rendition of "an Indian song, 'Big Chief Battle Ax.'"

Gilbert cartoon. Norton Company Mistrel Show.

Source:

Americanization, as contemporaries used the term, referred to the ongoing adaptation of immigrants and their children to "American" ways. Led by Theodore Roosevelt, who campaigned for the 1916 Republican presidential nomination on a platform calling for military Preparedness and the complete obliteration of any sentiment of ethnicity, those who questioned the loyalty of "hyphenated" Americans assumed that loyal Americans were, in T.R.'s phrase, "pro-America, first, last, and all the time, and not pro-anything else at all." Such "100% Americanism" made identity a zero-sum issue. An Italo-American, for example, was only 50% an American. Acculturation would reduce that 50% to zero. In such a scheme, any adoption of "American" ways meant a corresponding loss of ethnicity. The original notion of a "melting pot," in which each "ingredient" contributes something to the American national identity, was expressed at the conclusion of Israel Zangwill's 1907 play of that name:

Image from Peter C. Marzio, ed., A Nation of Nations: The

People Who Came to America as Seen Through Objects,

Prints, and Photographs at the Smithsonian Institution

(New York, 1976), 373.America is God's crucible, the Great Melting Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and re-forming! Here you stand, good folk, your 50 groups, with your fifty languages and histories, and your fifty blood hatreds and rivalries... A fig for your feuds and vendettas! Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Englishmen, Jews and Russians - into the crucible with you all! God is making the American.

This vision of multual adaptation quickly gave way to demands for complete conformity. Henry Ford, for example, sponsored his own "Melting Pot," as described in the Ford Times in 1916:

The "Melting Pot" exercises were dramatic in the extreme: A deckhand came down the gang plank of the ocean liner, represented in canvas facsimile. "What cargo?" was the hail he received. "About 230 hunkies," he called back. "Send 'em along and we'll see what the melting pot will do for them," said the other and from the ship came a line of immigrants, in the poor garments of their native lands. Into the gaping pot they went. Then six instructors of the Ford school, with long ladles, started stirring. "Stir! Stir!" urged the superintendent of the school. The six bent to greater efforts. From the pot fluttered a flag, held high, then the first of the finished product of the pot appeared, waving his hat. The crowd cheered as he mounted the edge and came down the steps on the side. Many others followed him, gathering in two groups on each side of the cauldron. In contrast to the shabby rags they wore when they were unloaded from the ship, all wore neat suits. They were American in looks. And ask anyone of them what nationality he is, and the reply will come quickly, "American!" "Polish-American?" you might ask. "No, American," would be the answer. For they are taught in the Ford school that the hyphen is a minus sign.This is not how George N. Jeppson saw matters. Norton Company under his leadership held an annual folk festival whose centerpiece was a parade of festooned wagons and cars representing the various nationality groups which made up the work force.

Source: Image, c. 1917, from Norton Archives, Worcester Historical Museum.

Jeppson himself headed the Swedish Republican Association of Massachusetts, by far the largest ethnic political association in the state. He helped organize the annual Midsummer celebration, a city-wide orgy of Swedish ethnic breast-beating. And he promoted Swedish folk culture, especially song. In 1920 he brought the first postwar national convention of Swedish singing societies to Worcester.

Norton Company's Americanization efforts were anything but attempts to stamp out all traces of ethnic group subcultures. Instead the company openly extolled ethnicitiy. But it did not regard ethnic groups as all equally valuable. Here are the lyrics from a comic song written for a company dinner, circa 1908, to be sung to "Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, The Boys Are Marching," and printed on the menu:In our Norton Foremen's corps,

There are Yanks and Swedes galore,

But hardly an Hungarian, Italian, or Pole . . .The song ended with a Swedish-American toast to Jeppson, sung by Swedes and Yankees:

A skoal for our leader, George N. J.,

Hip, Hurra,

He is the man that sets the pace,

He is the man that steers us straight.Any version of the "melting pot" is an ideal type, not a description of what actually happened over the course of the century between the burning of the Charlestown convent and the Smith-Hoover presidential contest. For that period becoming "American" meant entering a culture in which European and other nationality groups contended with each other � as well as with their Yankee "hosts" � for pride of place. [8] It was a culture which insisted upon the salience of ethnic stereotypes. In 1883, for example, the first Swedish Directory, a compilation of all the names, addresses, and occupations of Worcester's Swedes, contained this joke, in Swedish. The priest asks:

Patrick, the widow Murphy says you stole one of her best pigs.

Yes, Father.

What have you done with it?

I slaughtered it and ate it up, Father.

Oh, Patrick, what will you answer on Judgment Day when you stand face-to-face with the widow and her pig and she accuses you of having stolen it?

Father, did you say the pig will be there?

Yes, of course I said that!

Well then, I would answer: "Mrs. Murphy, now you have your pig back!"Few of the Directory's readers had been in the United States for more than a couple of years. Yet they were already learning "Pat and Mike" jokes � in Swedish!. This suggests that ethnicity itself was a form of acculturation rather than an alternative to it. To think otherwise � to assume that as members of a group became more "American," as Norton's Swedish employees leaned to "feel at home," for example, they became less ethnic, less insistent upon their Swedish identity � is to adopt the arithmetic of the nativists of the 1910s and 1920s with their calls for "100% Americanism."

Acculturation and ethnicity could reinforce each other in complex ways. They could also, and did, work against each other as when American-born children rejected their parents' "Old Country ways." There was an equally complex interplay between the emerging national popular culture, as expressed in vaudeville, popular songs, and movies, and grassroots cultural expressions, as in the Norton Company's Foremen's Dinner appropriation of "Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the Boys Are Marching."

A Jewish-American View of Acculturation: "The Jazz Singer"

One can see many of these interrelationships at play in "Warner's Bros. Supreme Triumph," "The Jazz Singer." The first "talkie," it was based "The Day of Atonement," a short story by Samson Raphaelson. In the movie Al Jolson played Jakie Rabinowitz, son of Jewish immigrants. His father is a cantor in a synagogue on the Lower East Side of New York City who expects Jakie to follow in his footsteps. But Jakie wants to sing "American" music. On the evening of Yom Kippur, a thirteen-year-old Jakie is supposed to sing the Kol Nidre for the first time with his father. A neighbor brings the unwelcome news that Jakie is instead singing "raggy time" songs at a saloon. Cantor Rabinowitz, outraged, finds Jakie performing "Waitin' For the Robert E. Lee," one of Jolson's signature songs. He drags his son off the stage. Determined to teach Jakie a lesson for "debasing" the voice God gave him, the father administers a thorough beating (off screen). Jakie runs away, taking only a picture of his mother.

Jazz singer film poster. "Years later - - and three thousand miles from home," a title reads, "Jakie Rabinowitz had become Jack Robin - - the Cantor's son, a jazz singer. But fame was still an uncaptured bubble. . . ." Jack is auditioning before a live audience in a San Francisco cabaret. He sings one song and then says to the crowd:

Wait a minute! Wait a minute! You ain't heard nothin' yet. Wait a minute, I tell ya, you ain't heard nothin'! Do you wanna hear 'Toot, Toot, Tootsie!'? All right, hold on, hold on. Lou [the band leader], Listen. Play 'Toot, Toot, Tootsie!' Three choruses, you understand. In the third chorus I whistle. Now give it to 'em hard and heavy. Go right ahead! [Real Player video available at the Al Jolson Society Official Website. Click on Works and then on Film.]

"You ain't heard nothin' yet" was a Jolson trademark, a line he had used countless times, as was the song "Toot, Toot, Tootsie." In the audience is a beautiful woman, a dancer, who befriends Jack Robin and gets him a job on the same vaudeville circuit as herself. Jack falls in love. He has not, however, forgotten his first love, his mother. He writes her regular letters. A title reads:

"Dear Mama: I'm getting along great, making $250.00 a week. A wonderful girl, Mary Dale, got me my big chance. Write me c/o State Theater in Chicago. Last time you forgot and addressed me Jakie Rabinowitz. Jack Robin is my name now. Your loving son, Jakie"

Signing the letter in which he reminded his mother of his new name "Jakie" emphasizes the competing claims on his identity. Is he really Jack Robin or still Jakie Rabinowitz? In Chicago he attends a concert of sacred songs by a famous cantor. Soon after he gets his big break, an offer to star in a new show on Broadway, "April Follies." The titles read: "NEW YORK! BROADWAY! HOME! MOTHER!" He arrives in New York on his father's sixtieth birthday and rushes from the station to their tenement apartment. His father is out, but he has a joyful reunion with his mother. He gives her a diamond necklace, promises that, if the show proves a hit, he will move his parents up to the Bronx, and sits at the piano and sings for her. It is an Irving Berlin tune, "Blue Skies." As he finishes the song, his father enters. They renew their old quarrel. "You dare to bring your jazz songs into my house! I taught you to sing the songs of Israel � to take my place in the synagogue!" Jack retorts: "You're of the old world! If you were born here, you'd feel the same as I do � tradition is all right, but this is another day! I'll live my life as I see fit!"

Al Jolson poster promoting the Jazz Singer. A few weeks later a neighbor seeks Jack out at rehearsal. "Tomorrow, the Day of Atonement - they want you should sing in the synagogue, Jakie . . . your father � he is very sick � since the day you were there." Jakie replies: "Our show opens tomorrow night � it's the chance I've dreamed of for years!" The neighbor bursts out: "Would you be the first Rabinowitz in five generations to fail your God?" Jakie says: "We in the show business have our religion, too � on every day � the show must go on!" Here is the choice: Is he Jakie Rabinowitz, the cantor's son, or Jack Robin, the jazz singer? His mother visits him backstage to tell him that his father is dying and that his last wish is that Jakie sing the Kol Nidre. Mary Dale reminds him of his commitment to his career. Jakie tells his mother he must seize his chance to become a star. He goes off to rehearse his big number, and his mother leaves. He goes after her. He sees his father who tells him: "My son � I love you." Mary and the show's producer turn up. Will Jakie sing in the synagogue? The producer tells him that, if he does, it will be the end of his career.

The film cuts to the theatre. It is opening night. "Ladies and Gentlemen, there will be no performance this evening �" The film cuts to the synagogue where Jakie is leading the service. His father's dying words are: "Mamma, we have our son again." The next night the show opens, and Jack Robin scores an enormous triumph. The movie closes as, in blackface, he sings "Mammy" to his mother in the audience.

All of the dichotomies dissolve. The Yom Kippur service and the Broadway show both go on. Cantor Rabinowitz's son fulfills the family tradition and realizes his ambition to live his own life. Jakie Rabinowitz can be Jack Robin and Jakie Rabinowitz can be Jack Robin. He can please his Jewish mother and his gentile girlfriend.

The exchange between Jakie and his father on the latter's birthday is especially sailent in this context:

Cantor Rabinowitz: You dare to bring your jazz songs into my house! I taught you to sing the songs of Israel � to take my place in the synagogue!

Jack: You're of the old world! If you were born here, you'd feel the same as I do � tradition is all right, but this is another day! I'll live my life as I see fit!

Jack's retort that, if his father had been born in the U.S., he'd feel as Jack does, directly contradicted one of the most important anti-semitic claims of the time. This was that, as Hiram Wesley Evans, Ku Klux Klan Imperial Wizard, phrased it, "not in a thousand years of continuous residence would he [the Jew] form basic attachments comparable to those the older type of immigrant would form within a year." Evans explained in a Klan Day address at the Texas State Fair in Dallas, October 24, 1923:

As a race the Jewish are law abiding. They are of physically wholesome stock, for the most part untainted by immoralities among themselves. They are mentally alert. They are a family people, reverently and eugenically responsive to God's laws in the home. But their homes are not American but Jewish homes, into which we cannot go and from which they will never emerge for a real intermingling with America. [9]

The adverb "eugenically" is particularly revealing. Evans hitched the Klan's claims to intellectual respectability to the emerging science of Eugenics. Historians pay too little attention to the eugenics movement of the first third or so of the twentieth century and less to the biological research upon which it was based. [10] But Eugenics, the study of how to identify good and bad "stock," was taught in high school and college curricula across the country. Virtually every biology textbook devoted at least a chapter to it. At its core was the notion, borrowed from the early nineteenth-century thinker Lamarck, that acquired characteristics could be inherited. Thus, in Frederick Jackson Turner's celebrated "frontier thesis," the experience of "opening" the frontier shaped the American character. In Evans' view, thousands of years of persecution had similarly but more deeply imprinted certain traits upon the Jews. The "indelible impress" of persecution "is there, marked by generation after generation of unchanging and unchangeable racial characteristics." Among these is an inherited inability to feel patriotism. "For ages . . . he has been a wanderer upon the face of the earth. . . .Into his life has come no national attachment. To him, patriotism, as the Anglo-Saxon feels it, is impossible." To this "The Jazz Singer" offers a dramatic rebuttal. It does so by making Jakie want to sing "American" songs. Who wrote this "American" music? Irving Berlin, another immigrant Jew, for one.

Purists have been quick to point out that Jolson was not a "jazz singer" and that neither "Waitin' for the Robert E. Lee" nor "Blue Skies" were jazz songs. Louis Armstrong, they note, was inventing a whole new way of singing in the late 1920s, as he had of playing, which would shape jazz for decades. Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, James P. Johnson and others were inventing jazz music. Irving Berlin did not write jazz. On the other hand, the movie took the time to indicate exactly what a "Jazz Singer" was. Jakie gave his mother a demonstration. He sang the Berlin song straight and then "jazzed it up," i.e., speeded up the tempo. [An extended digression on the early use of "authentic" jazz in the movies is here.]

There is another dimension to the way the movie used the term "jazz." A few years earlier Henry Ford, as part of his crusade to eliminate the Jewish influence in American life, singled out Berlin and jazz music as especially pernicious threats. Jews, led by Berlin, now controlled the music publishing houses, he charged first in the pages of his Dearborn Independent and then in The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem. They used this power to drive out genuine "American" music and to substitute the "mush" and "slush" of jazz which appealed only to the "basest" tastes and instincts. Just as Jakie's outburst about being born in America and therefore wanting to sing "American" music was a riposte to eugenics advocates who claimed Jews could not feel patriotism, the film's choice of a title and of a Berlin song to exemplify American music directly challenged Ford's anti-Semitic claims. Jerome Kern, himself a Jew, put the matter succinctly. Asked to comment on Irving Berlin's "place" in American music, he responded: "Irving Berlin doesn't have a 'place' in American music. Irving Berlin is American music."

Becoming "American," "The Jazz Singer" asserted, does not require the repudiation of one's ethnic heritage. Acculturation can, and should, accommodate ethnicity. This is the same claim Norton Swedes and Worcester Irish Catholics made, the former in joining the KKK via the Ericson Lodge, the latter in opposing the KKK by joining the Knights of Columbus. Both saw their actions as asserting their essential American identity even as they continued their long and bitter rivalry. Both also routinely staged minstrel shows. "Passing from light into dark" was a way of staking the claim that ethnic identity was no obstacle to being a real American. Race was.

An extended digression on another "jazz singer": Eddie Cantor and making "Whoopee!"

Based upon Owen Davis's comedy, "The Nervous Wreck," the musical comedy "Whoopee!" was a big hit on Broadway in 1928. Produced by Florenz Ziegfeld, it starred Eddie Cantor. It was filmed in 1930, with Ziegfeld and Samuel Goldwyn as co-producers and with virtually the entire Broadway cast recreating their roles. Cantor played Henry Williams, a neurasthenic who heads to a dude ranch in Arizona along with his nurse, Mary Custer, in search of peace and quiet. In a parallel plot Wanenis, the son of an Indian chief, loves a white heiress, Sally Morgan, whose father has forbidden their marriage. Henry finds himself accused of running off with Sally when her attempt to elope with Wanenis fails. She has left a note in which she writes that she and Henry have eloped. Since Sally's other suitor is the local sheriff, Henry seeks refuge on the reservation, where disguised as an Indian, he bargains over the price of a rug with a tourist. How can he stay in disguise? As soon as he opens his mouth, he will reveal himself as a white man. Henry hits upon a solution that made the scene the most celebrated of the film's many comic bits. He speaks Yiddish! All ends happily when it turns out that Wanenis is not really an Indian; he was merely raised as one. Since race and not acculturation is what counts, he and Sally can now marry. Henry, for his part, finally realizes that his nurse loves him, and they too marry. Marriage solemnizes racial purity; a trope Hollywood used over and over.

Cantor, like Jolson, was the son of Jewish immigrants. He too grew up in the "ghetto" on the Lower East Side and then went into vaudeville. He too became a star. While Jolson specialized in the big sentimental ballad, like "Mammy" or "Sonny Boy," Cantor's forte was comedy, usually slightly risqu�. In "Whoopee!" for example, his nurse has followed him to a nearby settlement. Henry is disguised in blackface, thanks to a comic accident with a stove. She too is in disguise, as a cowboy complete with mustache. She immediately recognizes Henry and accuses him of loving Sally. Henry, who does not recognize her, protests that he does not. Relieved and overjoyed, Mary offers to kiss him. "Hey, what sort of cowboy are you anyway?" is Henry's startled reply.

Like Jakie Rabinowitz, Cantor, born Edward Israel Iskowitz, changed his name when he went into show business. The name he chose identified both his ethnic background and his ambition to be a singer. Yet Henry Williams was supposed to be a WASP with inherited millions. When Henry gets into trouble, he too passes "from light into dark," first pretending to be African American and then Indian. In the latter guise, to keep from being found out, he adopts a thick Jewish accent. A Jew, playing a Yankee pretending to be an Indian, spoke a combination of broken English and Yiddish. And the audiences loved it. This came as no surprise. Fanny Brice, another Jewish-American vaudeville star, who, like Cantor, often headlined with Ziegfeld's Follies on Broadway, was almost as well known for her "Look at Me, I'm an Indian," sung in a thick Jewish accent, as for "Second-Hand Rose."

Giving the bit a further spin, Henry Williams spoke like a Jewish immigrant peddler as he bargained over the price of a rug. Had a gentile played Williams, the scene would have proved highly offensive to Jewish members of the audience. But everyone knew Cantor was "passing" as a gentile. In case they didn't, the show incorporated several jokes where Cantor's background is made explicit. In one, Wanenis is lamenting that, despite all of his attempts to adopt the white man's ways, Sally's father will not accept him. "I even went to your schools," he says. "You went to Hebrew School?" Henry responds.

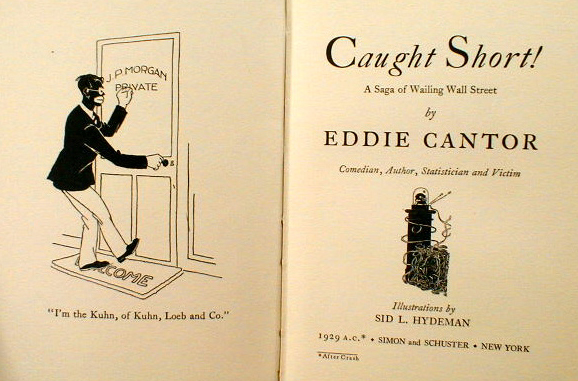

Following the stock market crash, Cantor collaborated with artist Sid Hydeman on Caught Short, a set of comic sketches about buying stock "on the margin" during the great bull market and then watching one's investments turn to dust. In one cartoon, Cantor books a hotel room on the nineteenth floor. The clerk asks: "Do you want it for sleeping or jumping?" Cantor described himself on the title page as "comedian, author, statistician, and victim." The subtitle puns on the "Wailing Wall," a place sacred to Jews. The cartoon on the facing page is a pun as well, a "coon" joke which also pokes fun at a well-known Jewish investment bank. It was the sort of "fresh material" the minstrel in the Norton Spirit cartoon of 1917 was seeking.

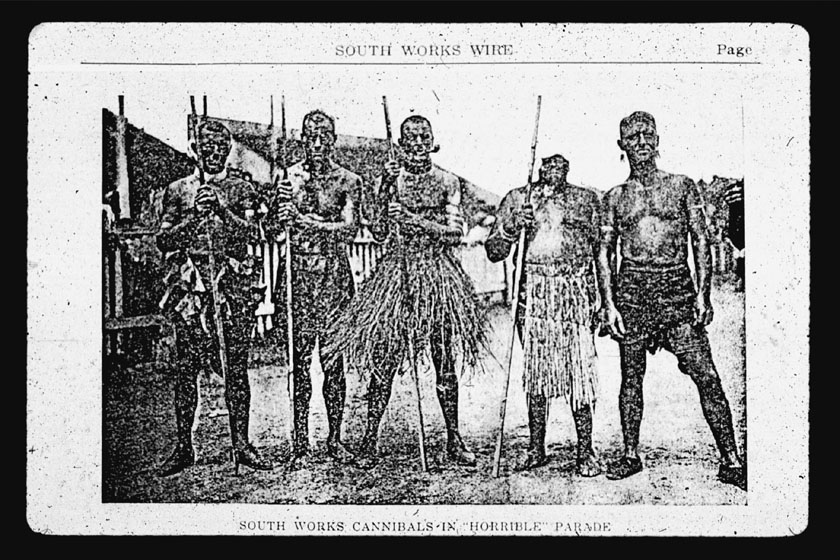

Consider in this context the "Parade of the Horribles" at the annual Field Day sponsored by the American Steel and Wire Company in Worcester in the years surrounding World War I. Who were the "Horribles"? They were employees dressed up in bizarre costumes, often with ethnic and/or racial themes. The most "horrible" won a prize. In 1921 the winners were the "South Works Cannibals," complete with grass skirts, spears, cork make-up, and earrings, pictured here as photographed for the Company newsletter.

The South Works were located in Quinsigamond Village, the most Swedish section of Worcester. Some of the "Cannibals's" sisters, members of the Swedish Women's Gymnastic Club, put on semi-annual shows for charity in the much more refined precincts of Tuckerman Hall, home of the Worcester Women's Club. The first portion of these shows, which attracted large audiences and significant coverage in the English-language newspapers, consisted of an exhibition of Swedish gymnastics. After intermission came a musical review, loosely modelled upon Ziegfeld's Follies. The gymnasts too were attracted to the South Seas. On other occasions, they chose to be geishas, or Swiss Misses, or Little Dutch Girls. Like their brothers among the "Cannibals," they presumably harbored no malice toward the Japanese or the Swiss or the Dutch or South Sea Islanders. They were simply looking for colorful costumes and a theme for their performances. [11]

Where did the "Horribles" get their notions of "Cannibals"? From the same sources the gymnasts got theirs of South Sea maidens. They appropriated the grass skirts, the ukeles, the leas and floral headdresses from the movies and popular literature. So too the spears and the blackened skin of the "Cannibals." The idea of staging a "revue" in exotic � albeit decorous � costume came from Broadway. During the 1920s "revues" overshadowed musical comedies. In 1928, for example, Time chose Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr. as its "Man of the Year." [For an extended discussion of "revues," see "Revues and Other Vanities: The Commodification of Fantasy in the 1920s." This is part of a project on "American History and Culture on the Web," supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.]

Some forms of ethnic and racial play hit closer to home. One was a "Comic Boxing Match," also staged during the 1921 Field Day and described in the American Steel and Wire newsletter. It pitted "Swen Sullivan of Italy" against Patrick Mohammed, the Polish Wonder." On the face of it, this might appear a playful representation of the Company as a melting pot � a fusion, perhaps a confusion, of Swede, Irish, Italian, Syrian, and Pole. But Patrick and Swen were comic figures precisely because everyone on the field that day knew there could never be an Irish Syrian from Poland. And a Swedish Irishman? About as likely as a Native American speaking Yiddish. The referee was "Jack Johnson," who strode into the ring carrying a three-foot razor with which to enforce his decisions. Here was one stereotype upon which all others could agree. The real Jack Johnson had been the heavyweight champion against whom a succession of "great white hopes" had contended. He would have needed no razor. [12] His presence, however, reminded everyone � Swedes, Irish, Italians, Syrians, and Poles alike � that just like "Jack Johnson" and "Rastus," they too were first and foremost perceived as stereotypes before they were individuals. Perceived by whom? Instead of answering "by the host culture," we should recall that everyone attending the Field Day was familiar with the ethnic stereotypes sent up in the "Comic Boxing Match."

This makes Cantor's use of Yiddish while playing a WASP pretending to be an Indian so daring. In playing with stereotypes he was playing with fire. It also explains the "Kuhn/coon" joke and the pun on "wailing Wall Street." Jews, like other nationality and ethnic groups, had to come to terms with stereotypes, often highly insulting, about themselves. Jews stereotypically worshipped money. They also controlled international finance, if Henry Ford were to be believed. So Cantor, self-described "victim" of the crash, wore his ethnicity on his sleeve. He also reminded white readers of the difference between "Kuhn" and "coon." "Swen Sullivan of Italy" and "Patrick Mohammed, the Polish Wonder" represented a similar form of play.

Cantor moved into radio with a long-running comedy program the year after he made "Whoopee!" A few years later another second-generation Jewish comedian, Jack Benny, scored an even greater success. Like Cantor in "Whoopee," Benny played a gentile, and also one with a character trait stereotypically associated with Jews. He worshipped money. Benny got the longest laugh in radio history with this gag:

Stick-up man: "Your money or your life!"

Benny: [a long silence]

Stick-up man: "I said 'Your money or your life!'"

Benny [peevishly]: "I'm thinking! I'm thinking!"Benny, unlike Jolson and Cantor, did not appear in blackface. Instead he cast Eddie Anderson as his black valet, Rochester. Over the decades, Rochester became less and less a stereotype. But Benny's miserliness became more pronounced each season as his writers looked for new ways to tell the same jokes. In one episode, a Treasury official from Fort Knox visited Benny to observe his security measures. These included surrounding his vault with a moat complete with alligators. Here again the jokes worked because the audience was complicit. They knew that Benny was Jewish. They knew through fan magazines and newspaper gossip columns of his personal generosity. Benny, like Cantor in "Whoopee!" and Jolson in "The Singing Fool," "passed" as a gentile. None used makeup. Benny did turn his blue eyes � in the 1920s, '30s, and '40s used in Nazi propaganda as a sign of Aryan origin � into a standing joke. His character was as vain as he was greedy. And he was especially vain about how blue his eyes were.

Benny, in addition, affected distinctive vocal rhythmns along with matching gestures, facial expressions, and walk. These too involved the audience as accomplices as all were stereotypes associated with gay men. Benny employed them in his character's endless efforts at seducing women. This too stood "passing" on its head. [13]

Michael Rogin is right, I think, to argue that blackface provided a way for Jewish immigrants from Europe and their American-born children to claim membership in American nationality. [14] Yet, their appropriation of minstelsy is part of a much wider phenomenon as the examples of the shows put on by Norton Company and by Irish-Catholic parishes suggest. Nor was blackface solely or even primarily a way for ethnic groups to assert their own place in American public life, even though it certainly could fulfill that function.

After all, the longest-running and most successful use of minstrelsy and blackface in the twentieth century was "Amos 'n Andy." Starting in March 1928, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, both of whom had appeared in minstrel shows as young men, launched a daily fifteen-minute radio series detailing the misadventures of the sensible, happily married Amos and the would-be Don Juan Andy. They continuously added characters, such as the slow-moving janitor, Nick O. Demus (aka "Lightning"), the shyster lawyer, Algonquin J. Calhoun, the fast-talking Kingfish and his sharp-tongued wife Saphire, and other members of the Mystic Knights of the Sea Lodge, their friends, relatives, and neighbors. Within months, "Amos 'n Andy" became the first radio program to have a national hookup. And for decades their faithful audience tuned in by the millions. [15] What was the secret of their success? Their show, they wrote in 1942, upheld traditional values. We have always kept the material "clean," they noted. "Radio and the world may have undergone some changes--but people and human values haven't." Among those values was a secure racial hierarchy:

We still think the "Perfect Song," which was written for "The Birth of a Nation," a perfect song for the theme melody of "Amos 'n' Andy." � Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, "If we had it to do OVER AGAIN": A Great Radio Pair Look Back Over Their Career on Their Fourteenth Anniversary, Movie Radio Guide, March 1942 [For a midi recording, click here. For a image of the cover of a 1937 edition of the sheet music with Gosden and Correll in blackface, click here.]

"Passing from dark into light": The career of Warner Oland

A secure racial hierarchy kept Asians in their place as firmly as it did blacks, and with many of the same means. Werner Oland, a Swedish immigrant, played Cantor Rabinowitz in "The Jazz Singer." He had just finished co-starring as the villianous Chris Buckwell in "Old San Francisco." Buckwell is a Chinese "vice lord," the boss of a criminal network who passes himself off as white when he is outside Chinatown. Within it he remains a "depraved heathen," as a title describes him. He covets the Vasquez "Rancho," one of the few remaining in the hands of the original Mexican owners. He also covets the beautiful Delores Vasquez. But he makes the mistake of telling her of his "Oriental blood." This leads her to recoil from his advances. In any event, her heart belongs to a handsome Irish-American, Terrence O'Shaughnessy. But her grandfather refuses any suitor who is not of pure Spanish descent. Frustrated by his inability to gain either Delores or the Vasquez land, Buckwell kidnaps her and turns her over to a white slavery ring run by his Chinese henchmen. Her grandfather dies, trying to defend her. Just as the unimaginable is about to happen, the great earthquake of 1906 strikes. Amid the chaos and destruction, O'Shaughnessy rescues Delores. Buckwell's imposture is exposed. Their union marks the beginning of a "new" San Francisco. The union of Chinese and white blood, however, would have been a tragedy, one so great that its prevention justifies dramatically the massive destruction and carnage of the earthquake. Here, as in "Whoopee!" and numerous other films, marriage solemnizes racial purity.

Oland got the part not only because of his acting skills but because of his "Oriental" features, the same combination that won him the role of Cantor Rabinowitz. "Old San Francisco" thus features a Swede playing a Chinese pretending to be white. The character is thoroughly acculturated. He speaks English without a trace of a Chinese accent. He attends Christian religious services. He conforms outwardly in every way. But, he remains Chinese. As such he embodies the "Yellow Peril." He trafficks in opium, gambling, and white slavery. He lusts after Delores.

"Old San Francisco" reprised many of the themes of "Birth of a Nation." [Available online at the University of New Orleans.] In it the villain is Silas Lynch, a mulatto and close associate of Radical Republican Congressman Austin Stoneman (modelled upon Thaddeus Stevens). Stoneman seeks racial equality, a position even fellow Radical, Senator Charles Sumner, thinks extreme. But Stoneman is implacable and sends Lynch to South Carolina to enforce his radical measures. A title describes Lynch as "a traitor to his white patron and a greater traitor to his own people, whom he plans to lead by an evil way to build himself a throne of vaulting power." Lynch persuades local blacks to refuse to work for whites. He uses his black troops to force whites to do his bidding. He misuses Freedman's Bureau funds to support idle blacks whom he then enrolls as voters. All of this is bad enough, but his worst crime is his desire for Congressman Stoneman's daughter Elsie. She is in love with the scion of an old South Carolina family, Ben Cameron. Lynch spies them kissing in a garden. But Elsie and Ben realize they cannot marry since she must be loyal to her father and he must defend the white South from Radical Reconstruction.

Lynch wins the lieutenant governorship in an election in which whites are barred from voting. The new legislature, dominated by blacks, passes, among other outrages, a bill permitting racial intermarriage. As Lynch's abuse of power grows, Ben Cameron decides to take action. He forms the Ku Klux Klan which a title calls "the organization that saved the South from the anarchy of black rule, but not without the shedding of more blood than at Gettysburg." The greatest danger is to white womanhood, embodied first in Cameron's sister, Flora, who dies in a fall while fleeing the amorous attentions of a black militia officer, and then in Elsie Stoneman to whom Lynch proposes. As Delores Vasquez would do a decade later, she recoils and threatens him with a "horsewhipping for his insolence." "Lynch, drunk with wine and power, orders his henchmen to hurry preparations for a forced marriage." Elsie faints into Lynch's arms. Her father arrives, and Lynch informs him of his plans: "I want to marry a white woman � The lady I want to marry is your daughter." Stoneham, despite his own earlier dalliance with a black servant, is furious. But Lynch has the upper hand.

Fortunately for Elsie's honor, Ben Cameron and four hundred other Knights of the KKK are gathering to break Lynch's power. They arrive just in the nick of time. White supremacy restored, Elsie and Ben marry. [16]

In both films, the villain sought wealth, social acceptance, power, and the hand of the daughter of a prominent family � despite being barred from all of these by his race. In both the villain mastered all of the outward forms of white society but inwardly remained true to his racial origins. In both a stalwart young hero thwarted his diabolical schemes and then married the heroine. This signalled, in both films, the start of a new era, one based upon racial purity which is thematized in both by the unsuccessful attempted rape of the heroine. Her honor saved, society can renew itself.

Not only do the two films emphasize the same themes, but in both the villain was played by a white actor. In "Birth of a Nation" it was George Siegmann who, in 1927, would play the cruel slaveholder Simon Legree in "Uncle Tom's Cabin." In another parallel both movies inspired vigorous protests by offended African and Asian Americans. The premiere of "Old San Francisco" led to a riot in that city. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) led a boycott of "Birth of a Nation."

The Klan of the 1920s would scarcely have endorsed "Old San Francisco" with its heralding of the marriage of Delores Vasquez and Terrance O'Shaughnessy as the beginning of a new era. For them true Americans were Protestant and of northern European stock. This makes "Old San Francisco's" appropriation of plot devices and thematic material from "Birth of a Nation" all the more revealing. In both films the hero and heroine are kept apart by ethnic or sectional animosities. These are shown to be less essential than race. White Northerners and Southerners can reunite, Irish and Spanish-Americans can unite, because race is enduring while sectional and ethnic antagonisms are not.

Warner Oland's success in "Old San Francisco" led to him getting the role of another incarnation of the Yellow Peril, the "mysterious" Dr. Fu Manchu. His creator, the Irish-born Sax Rohmer, put this description in the mouth of Fu's antagonist, Nayland Smith:

"Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present, with all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government -- which, however, already has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man." -- Nayland Smith to Dr. Petrie, The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu : Being a Somewhat Detailed Account of the Amazing Adventures of Nayland Smith in His Trailing of the Sinister Chinaman (New York, 1913), Chapter 2.

Rohmer offered several accounts of how he came up with the idea for Fu Manchu. They differ in several details. However, the broad outline seems indisputable. Rohmer was a young reporter with ambitions of becoming a writer of fiction. He accepted an assignment in the Limehouse section of London to investigate the criminal activities of a "Mr. King," a Chinese master criminal who supposedly controlled the gambling and opium in the district. Rohmer learned little beyond second-hand tales. Then, late one night, as he was about to head home, a limosine pulled into a narrow alley:

The car pulled up less than ten yards from where I stood. A smart chauffeur switched on the inside light, jumped out and opened the door for his passengers. I saw a tall and very dignified man alight, Chinese, but different from any Chinese I had ever met. He wore a long, black topcoat and a queer astrakhan cap. He strode into the house. He was followed by an Arab girl, or she may have been an Egyptian. She reminded me of an Edmund Dulac illustration for the Arabian Nights. The chauffer closed the car door, jumped to his seat, and backed out the way he had come in. The headlights faded in the mist . . . and Dr. Fu Manchu was born!

If the tall Chinese was the elusive "Mr. King" or someone else, I cannot pretend to say; but that he was a man of power and enormous authority I never doubted. As I walked on through the fog I imagined that inside that cheap-looking dwelling, unknown to all but a chosen few, unvisited by the police, were luxurious apartments, Orientally furnished, cushioned and perfumed. I saw a spot of Eastern magnificence, a jewel in the grimy casket of Limehouse. That very night, alone in my room, I searched through memories of the East, finding a pedigree for the beautiful girl I had seen through the fog. And she became Karamaneh (an Arabic word meaning a confidential slave), an unwilling instrument of the Chinese doctor.

Little by little, that night and on many more nights, I built up Dr. Fu Manchu, until at last I could both see and hear him. His knowledge of science surpassed that of any scientist in the Western world. He controlled every secret society in the East. I seemed to hear a sibilant voice saying, "It is your belief that you have made me; it is mine that I shall live when you are smoke." -- Sax Rohmer, "How Fu Manchu Was Born," This Week, September 29, 1957.

Fu Manchu strongly resembled Arthur Conan Doyle's Professor Moriarity, the evil genius of crime who was Sherlock Holmes' most formidable antagonist. Both had enjoyed advanced educations in Europe's finest universities; both employed beautiful women in their nefarious schemes; both had powerful intellects that enabled them to outwit the authorities.

What made Rohmer's version of the criminal mastermind so enduringly popular was his use of the "yellow peril" motif. Fu Manchu had learned western languages � his English was flawless; he had mastered western sciences, especially medicine. Yet, like Chris Buckwell in "Old San Francisco," he remained an implacable enemy of western values. In another account of the creation of the character, Rohmer wrote that Fu Manchu had become so real to him that he and the insidious doctor engaged in a dialogue:

". . . Do you dream that your Mr. Commissioner Nayland Smith can conquer me? That my mastery of the secret sects of the East can be met by the simple efficiency of the West? I shall prove a monster which neither you nor those you have created to assist you can hope to conquer. . . ."

He was so real that I answered him. One listening must have assumed that I, sitting alone in my room with the grey light of dawn just beginning to peep through the curtains, had become demented. It was not so. I had created something, and it was to the Mandarin Fu Manchu that I replied: "It will be a square fight, but a fight to the finish, Dr. Fu Manchu."

"A member of my family," he answered, "a mandarin of my rank, never breaks his word. For myself I ask nothing. I hold the key which unlocks the hearts of those who belong to every secret society in the East, including the Thugs. I command every Tong in China. My knowledge of medicine exceeds that of any doctor in the Western world. I shall restore the lost glories of China -- my China. When your Western civilization, as you are pleased to term it, has exterminated itself, when from the air you have bombed to destruction your palaces and your cathedrals, when in your blindness you have permitted machines to obliterate humanity, I shall arise. I shall survey the smoking ashes which once were England, the ruins that were France, the red dust of Germany, the distant fire that was the United States. Then I shall laugh. My hour at last! Your Nayland Smith, your Scotland Yard, your Dr. Petrie, yourself, all will be blotted out. But China -- my China -- its willing millions awaiting my word -- China, then, will come into her own. The dusk of the West will have fallen: the dawn of the East will have come." -- Sax Rohmer, "Meet Dr. Fu Manchu," from MEET THE DETECTIVE, edited by Cecil Madden, published by the Telegraph Press, New York, 1935.

Oland made three Fu Manchu films, starting with "The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu" in 1929. In each his evil scheme is foiled by Nayland Smith, purportedly a nephew of Sherlock Holmes, and Smith's doctor friend, Jack Petrie. [For a detailed plot summary of the first, enlivened with sound clips, go to The Missing Link site.] Oland then found a new Oriental character to play, Charlie Chan. According to Associated Press reporter Patrick Williams in a column, no longer available online, celebrating the seventy-fifth anniversary of the first Chan mystery,

In 1924, Earl Derr Biggers, a Boston playwright and author, was contemplating a mystery set in tropical Honolulu, where he had vacationed four years earlier. Leafing through a stack of Honolulu newspapers to refresh his memory, the writer came across a small story about Apana [a real Chinese detective] and an opium arrest. Immediately, Biggers hit on the idea of a good-guy Chinese character for his mystery.

"Sinister and wicked Chinese were old stuff in mystery stories, but an amiable Chinese acting on the side of law and order had never been used up to that time," Bigger recounted in a 1931 Honolulu newspaper article.

Like Fu, Charlie was highly intelligent. He was not, however, an enemy of western values even though he remained faithful to Chinese traditions and was given to citing ersatz Chinese aphorisms. When Oland unexpectedly died in 1938 just before the shooting of what was to have been his seventeenth Chan film, Twentieth-Century Fox turned it into "Mr. Moto's Gamble" with another European actor, Peter Lorre, as Chan's Japanese counterpart.

Oland's performance as Chris Buckwell so outraged Chinese Americans that those in San Francisco rioted at the premiere. Later, Chinese students at Columbia University boycotted an appearance by Sax Rohmer because they found the "yellow peril" stereotype he exploited in creating Fu Manchu so hateful. But, in 1935, Oland made a triumphal tour of China where he was surrounded by thousands of fans of Charlie Chan. Many refused to believe that Oland was not himself Chinese. [For more on Chan as the "good" Oriental, click here.]

Passing As A Cultural Trope

"Not only was I supposed to have a pet python, but I had my father's male victims turned over to me for torture, stripped; I then whipped them myself, uttering sadistic gleeful cries." -- Myrna Loy on her role as Fu Manchu's daughter in "The Mask of Fu Manchu."

Hollywood, as we have seen, routinely cast whites as Chinese and Japanese. Boris Karloff, pictured at right in a publicity still for "The Mask of Fu Manchu," replaced Warner Oland in the title role. Myna Loy, today remembered for playing Nora Charles opposite William Powell in "The Thin Man" series, played Fu's daughter � not Anna May Wong. In fact, Wong lost so many roles to Loy that she left Hollywood for several years and pursued her career in Europe. Japanese-American Sessue Hayakawa fared little better. [17] Peter Lorre played Mr. Moto. More notably, perhaps, the 1937 production of Pearl Buck's best-selling novel about the resilency of Chinese peasants, "The Good Earth," starred Paul Muni, an Austrian Jew who got his acting start on New York's Yiddish stage, as Wang Lung and Austrian-born Louise Rainer as O-Lan, a role for which Rainer won an Oscar. [18]

"Passing," so long as it meant going from "light into dark," was a commonplace of American popular culture. It was more. It was virtually a requirement. With the notable exceptions of Anna May Wong and Sessue Hayakawa, Asians were not cast as Asians. Whether the scripts called for villains or "good guys," "dragon ladies" or faithful wives, whites played the parts. Wong and Hayakawa did get some supporting roles. Similarly, a few blacks also broke into movies made by the major studios. Noble Johnson, who created his own production company in the early 1920s to make films for African American audiences, played supporting roles in "The Ten Commandments" and other silent films. He continued his career in the sound era. He was the native chief in "King Kong" (1932) and, far more remarkably, the Tartan Ivan in "The Most Dangerous Game," which was shot at the same time. This is the first instance, so far as I have been able to determine, of any black actor playing a white in a movie. In 1922 Allen "Farina" Hoskins appeared in the second "Our Gang" short. In 1927 James Lowe starred as Uncle Tom. And Stephin Fetchit launched his career in the 1927 silent "In Old Kentucky." For the most part, however, African Americans got work only in crowd scenes or playing servants.

Two related questions suggest themselves. Why was Hollywood so averse to casting Asian and African Americans? Why did white audiences so enjoy seeing white performers pass "from light into dark"? One avenue of approach to these questions is via a second look at the career of Al Jolson. Three of Jolson's most successful stage shows featured "Gus," a character Jolson first used in his minstrel show days. In "Sinbad" (1920 - 164 performances on Broadway) Gus was a porter who finds himself in several historic events. In "Bombo" (1921 - 219 performances on Broadway) Gus sailed with Christopher Columbus. In "Big Boy" (1924 - 180 performances on Broadway) Gus was a jockey and stablehand, the faithful retainer of an old white Kentucky family. The Broadway runs were followed by national tours. The most successful was "Big Boy" in which Jolson toured for three years. In 1930, Warner Brothers followed up "The Jazz Singer," the even more successful "The Singing Fool," and the box office disappointment "Mammy" with a film version of "Big Boy." [19]

In "Big Boy" Gus's family had worked for the Bedfords for generations. Indeed back in 1870 his grandfather had rescued John Bedford's fiance� from the evil John Bagby who had shot Bedford and kipnapped her. What is more, he had dragged Bagby back to justice at the end of a rope. This meant, Mrs. Bedford reminds her children, that Gus will ride their prize racehorse "Big Boy" in the Derby: "We Bedfords must never forget what our darkies remember." Nonetheless, her son contrives to have Gus fired so that another jockey can ride "Big Boy" and throw the Derby. Gus learns of, and stops, this wicked scheme. He then rides "Big Boy" to victory.

"Gus" offers several clues to the popularity of blackface and of white performers in Asian roles. Most obvious, perhaps, is the reinforcement of certain classic stereotypes -- the loyal "darky," the aristocratic white family that takes care of its faithful servants. "Gus" also allowed Jolson to do a type of humor otherwise out of bounds. For example, when "Gus" learns that Mrs. Bedford's son got him fired because he was being blackmailed over a bad check he had written, "Gus" immediately determines to retrieve it. Just then he sees Dolly Graham, one of the gang of blackmailers, slip it down her dress. "Gus" arranges to have the lights turned off in the restaurant where he is now working. There is much shrieking and clamor during the darkness. Dolly calls out: "Coley [another blackmailer], somebody is after the check!" Later, "Gus's" friend Joe asks:

"Did you get the check, Gus?"

"Did I get the check? Say, I'm an ol' check getter. When I set out to get me a check I . . . I . . . Oooooh, Mr. Joe, what must that woman think of me?" "Gus" holds up a piece of lingerie.At the same time, because Jolson is white, "Gus" says and does things that no African American could. Putting his hands inside a white woman's dress is the most flagrant case in point. But, it also was only possible to portray the adventures of "Gus's" grandfather because the actor beating up the white villain was himself white. So too with this exchange between "Gus" and the blackmailers. Gus approaches their table. They are arguing heatedly. "Gus" chides:

"Hey, hey, where do you think you are? You can't argue like this in a public place. This ain't your home, ya know!"

"Where did you come from?"

"A reindeer brought me!"

"Are you looking for trouble?"

"Yeah! Do ya got any?"The villain tries to punch "Gus" but misses. Then the lights go out. And the Jolson character attempts to grab the check.

"Gus" is, despite surface similarities, the direct opposite of the character made famous by Stephin Fetchit. "Gus" is quick-witted, quick moving, fearless, resourceful. Stephin Fetchit is slow of wit and of foot, frightened of his own shadow, and always at a loss as to what to do.

The tradition of rude humor was a staple of minstrel shows. At right are excerpts from the lyrics from a comic song from the 1850s. "Dinah Crow," who sings it, was Jim's sister. In the pre-Civil War minstrel shows "Dinah" was a white man, in blackface and a dress, who would accompany himself on the banjo and offer comic observations on daily life. The blackface meant the performer could speak bluntly. "Dinah" was not noted for her delicacy of expression. The crossdressing had a comparable effect. Here was a "woman" revealing the secrets of her own sex. If fashionable Broadway belles offended "Dinah's" sensibilities, then their behavior must truly be outrageous. [20]

She tried to show "de Broadway gals" a good example by only showing "de ankle, insted ob de calf." But the "Broadway gals" wear "de frock up to de moon," exposing "too much . . . unto de naked eye." New York, she lamented, was "a wicked place . . . for de gals wear false things, and tink it be no sin." They used "white paint and red, and salve for de lips, an a sham bishop behind, an a false pair ob hips." Then they promenaded "all day." For whom did they put on this show? Watching, peeping actually, is "a fellow" whose object is "to see where dat gal ties her garter."

In minstrelsy performers and audiences were accomplices. Performers pretended to be black � this holds for African-American ministrels as well who had to use cork makeup and conform to the stereotypes established by whites � and the audiences pretended to believe they were black. Mutual pretense created an imaginary space in which blacks were simultaneously stupid and intelligent, crude and tender, ignorant and sharp-eyed observers of the white world. It was permissable for "Dinah" to criticize white "gals" who "wear der petticoats so high, that too much is exposed unto de naked eye" in the bluntest terms, provided she did so in a comic dialect. "Gus" could paw the white Dolly. Blackface celebrates crude expressions and gestures.

In the 1924 Norton Company Minstrel Show "saluting" St. Patrick's Day, use of blackface permitted Swedish-Americans, Yankees, and other Norton employees to insult Worcester's Irish with unbridled enthusiam. It was the white skin beneath the cork which permitted such "uppitty" behavior.

"Showboat" made use of a fascinating variation. Helen Morgan, a white singer and actress, played the mulatto Julie without the use of makeup. This was acceptable because Julie was "passing." She had to look white. The only hint the audience is given of her racial origins is the fact that she taught Magnolia a song, "Can't Help Lovin' That Man Of Mine," which supposedly only African Americans knew. But, in asking white audiences to identify with Julie and to affirm her love for Bill and to thereby reject American racial boundaries, the show itself carefully observed them. The woman kissing Bill was a white pretending to be mulatto. Today, the estate of Oscar Hammerstein II refuses to permit performances of "Showboat" in which whites portray black characters. Not so in the original, nor in the first film version in which Morgan recreated her role, nor in the 1950s remake in which Ava Gardner played Julie.

"Birth of a Nation" provides another example. Here too performers and audiences were complicit. The villainous Silas Lynch lusted after the virginal Elsie Stoneman, who fainted in his arms in sheer terror when he announced his intention to force her to marry him. It was essential to the whole mythology of the Klu Klux Klan which the film celebrated that he almost succeed in forcing himself upon her. Ben Cameron, the founder of the Klan in the movie, must save her and, by extension, white womanhood, from the most terrible danger. For the same reason Lynch must menace her because he has black blood. But George Siegmann, the actor playing Lynch, could hold and caress Lillian Gish without violating racial taboos only because he was white. So too with Warner Oland in "Old San Francisco" and "The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu." In both films he had a beautiful white woman in his clutches. His capacity for evil derived from his "Oriental blood"; so did Fu Manchu's daughter's sadistic impulses in "The Mask of Fu Manchu." But it was the white Myrna Loy to whom her white victims grovelled. Similarly, Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto could "outfox" not only the wiliest white criminals but also the most clever white police because underneath their Oriental cunning was white skin.

There was no Asian equivalent to black minstrelsy. Swedish women gymnasts and performers in parochial school productions of "The Mikado" aside, few immigrants from Europe or their children could affirm their own American identity by assuming a Chinese or Japanese persona. But understanding the rules of "passing" was an important component of acculturation. These were, as I have tried to demonstrate, complex. And, as they applied to ethnic groups of European origins, they were in flux. Exploring this was at the heart of the Marx Brothers' comedy. [21]

Groucho played Yankees who had names like Otis B. Driftwood; brother Chico's characters were Italian with names like Fiorello. Harpo had no stable ethnic identity. He was pure id, appetite unregulated by superego. He neither needed nor used language. He simply grabbed whatever he wanted, usually sex and food.

In "A Night at the Opera" there are several scenes about Harpo and eating, each a virtuoso turn. Groucho and Chico, on the other hand, were masters of language which they turned and twisted to suit their own purposes. In "A Night at the Opera" they negotiate a contract for a promising tenor. They take turns objecting to each clause. They resolve these disputes by tearing off strips of the contract until each is left holding only a small fragment of paper. What is this last clause, Chico demands to know. Oh, Groucho responds, that is just the sanity clause. There was one in every contract. Chico shoots him a "You can't put that over on me" look and says: "Everybody knows there ain't no Santy Claus." [To hear the scene in RealAudio, click on the image.] Together the brothers turned every established WASP institution and practice � from the opera to horse racing to big game hunting to college life to diplomacy � to shambles.

Here again the trope is "passing." Like Cantor in "Whoopee!" the brothers do a number of jokes to remind the audience of their Jewish background. In "Animal Crackers," for example, they form a barbershop quartet, "from the House of David," to sing "Old Folks at Home." Yet Groucho's character is Captain Spaulding, "the African explorer." And Chico plays an Italian musician.

Ethnic Cultures and Mass Culture

The decade of the 1920s was one of ongoing cultural warfare centered around issues of race, ethnicity, and religion. Questions of who was a "real" American, of the place of Catholics in American public life, of the place of Jews, of immigrants from central and eastern Europe dominated politics. Advocates of "100% Americanism" won important early victories, such as Prohibition and immigration restriction. But "wets" and Catholics and blue-collar ethnics and their families found a political home inside the Democratic Party which would enable them to recoup some of their losses in the 1930s and 1940s. [This is the organizing theme of the 1920s section of the American History and Culture on the Web project I co-direct.]

These issues dominated much of the science of the day as the widespread acceptance of eugenics indicates. More than thirty states adopted laws banning interracial marriage and almost as many had programs of involuntary sterilization for those deemed "a burden upon the rest of us." These same issues dominated much of the debate over educational policy as school systems across the country adopted standardized tests, often developed in cooperation with leading eugenicists, and tracking schemes devised to give special attention to "gifted and talented" students who, not coincidentally, superintendents and principals presumed would include few Italians, Poles, or Greeks.

Advertising, as Roland Marchand and others have shown, promoted and reflected notions of "Anglo-conformity." From ads for skin cremes that would enable women to stay young to those for automobiles which promised mothers would no longer be "Marooned!" at home with young children one found white faces with regular features. There were no Roman noses; no one with olive skin. When ads used names, as they often did, they were Yankee names. [22] [For an especially egregious case in point, Lifebuoy's use of eugenics themes in its ads of the 1920s, click here.]

It was in the emerging mass culture that European immigrants and their children had an equal say. Mass culture in the 1920s, as Frank Couvares noted in the case of Hollywood, was a m�lange of ethnic and racial voices and faces. [23] Compared to what Henry May called the "citadels of culture," such as faculty positions at elite universities and editorships at prestigeous journals and publishing houses, members of European ethnic groups had far greater access to mass media. [24] They wrote many of the popular songs; they produced the movies; they starred on the vaudeville circuits and the legitimate stage. They wrote, produced, and starred in radio programs. In contrast, while second-generation immigrants did go to college in greater numbers during the 1920s, faculty and administrators, especially in elite institutions, remained overwhelmingly WASP. So too with editors and publishers. More second-generation immigrants were writing novels, short stories, poetry, and non-fiction in English. But few gained a wide readership. The shelves of libraries and bookstores were filled with WASP names.

The person going in to buy sheet music in the 1920s, on the other hand, would see the faces of Al Jolson, Bert Williams, and Fanny Brice on the covers. If that person continued down Main Street past the new movie "palace," he or she would pass posters advertising current and future shows. Pictures of Rudolph Valentino in "Son of the Sheik" or Ramon Novarro in "Ben-Hur" were part of everyday experience. If that person then went home and turned on the radio, Eddie Cantor or Jack Benny might be on.

What European ethnics used their access to the mass culture to say was often flippant, often funny, often mawkish. It was not trivial. They proclaimed that Catholics and Jews and "Hunkies" and others from southern and eastern Europe were the equals of self-styled "real" Americans. As the examples from Worcester show, ethnic communities eagerly embraced key elements of this mass culture and used them to similar but not identical ends. For they were engaged in battling each other quite as much as resisting discrimination at the hands of Yankees.