|

The Last Zapatista. Producer and director, Susan Lloyd. University of California Extension Center for Media and Independent Learning, 1995. 30-minute VHS video.

The video opens with a picture of Zapata, and quickly discusses the origins of the revolution. The filmmakers drastically reduce it from a messy, confusing and violent civil war lasting nearly a decade to a clear-cut battle between good and evil. An agronomist tells us about the Porfiriato (the 35-year dictatorship of Porfirio D�az that preceded the revolution); then Pantale�n, another campesino, the narrator, and Emiliano Zapata's daughter all eulogize Zapata.

After describing Zapata's betrayal and death at the hands of federal forces, the video shifts focus to 1994, and the 75th anniversary of his death. Why? In 1917 a new constitution was written for Mexico, one which contained many (then-) radical guarantees, such as free and secular education, worker's rights, and, in Article 27, limits on private property, national ownership of the land and subsoil resources, and land-reform and agrarian programs.

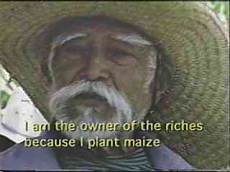

The video then connects events in modern-day Morelos to Subcommandante Marcos, the leader of today's Zapatistas, who says that "with the reform of Article 27, that door [to legal change] has been closed." The EZLN are shown as the direct heirs of the struggle of Emiliano Zapata in the early 20th century. The best part of The Last Zapatista comes at the end. A group of campesinos are filling sacks with corn and loading them onto a truck, and Emeterio Pantale�n starts to sing a traditional song. As he sings, one of the other men yells "�Viva Zapata!" at the end of each verse. For all the softly-voiced platitudes of the narrator and Pantale�n's previous wandering statements, this is when viewers can sense the power behind the meaning of what corn and the land to grow it mean to the campesinos of Morelos.

Although the time we, as viewers, spend with Pantale�n is certainly not wasted, the video is by no means an outstanding history of either the revolution or the Chiapas uprising. The revolution is simplified to the point where it is almost a clich� ("Zapata's cry of Tierra y Libertad inspired all the revolutionaries and their supporters"). There are historical mistakes as well (the video claims that Zapata was the leader of "all the Indians in the south of Mexico"—when in fact many Zapatistas were mestizos, not Indians, and the revolution affected large areas of the south, particularly Chiapas, very differently than it did Morelos). There are also a number of missed opportunities in the film. For example, during the Salinas ceremony, we are not sure why, exactly, the constitution has been changed. We hear little about NAFTA, neoliberalism, or the mechanisms by which Salinas' party, the PRI, has ruled in the name of Zapata and the revolution for 70 years. Although the video is rightly sympathetic, it is not a very solid treatment of the Chiapas uprising, either. At least it makes the basic connection that both groups were fighting for land and liberty. A much better film about the EZLN and the situation in Chiapas is Nettie Wild's A Place Called Chiapas (1998). Other issues need more explanation. For example, the campesinos' farming methods are, without discussion, held up as the best way to use the land, raising further questions. Do they really not use chemicals? Why not? Because they are committed organic farmers (the implication) or merely because of poor access to credit?

The segments featuring Emeterio Pantale�n are the most unique thing about this video, and even those raise some difficult questions, most of which have to do with his age and what he actually did. Assuming he was at least 10 years old in 1913-14 when he talks about participating in a battle with Zapata, that would make him at least 90 years old in 1995 when the movie was released. This would be only mildly remarkable if it weren't for the added fact that he still saddles and rides his horse every day, and still works in the fields growing corn by hand. This means that we should take at least some of what he has to say as evident of popular memory about the revolution and life during the Porfiriato, rather than his own lived experience. For example, when Emeterio Pantale�n says that "[before the revolution] the hacienda owners lashed at us with whips and took our lands away, after that we didn't have anything. They made us work until 6 at night, without rest" he is probably not speaking from personal experience. Another question centers around the relationship of the video's writer/director, Susan Lloyd, to its narrator. Whose voice is heard when the narrator refers to Emeterio Pantale�n as her grandfather? Due to its simplifications of the revolution, the mechanics of rule and class politics in Mexico, and the rebellion in Chiapas, I would be loathe to recommend this video for a class that was unfamiliar with the history of 20th-century Mexico. For a group of students that knows it, though, these weaknesses would provide useful openings for discussion—and since the video runs less than a half-hour, there would be time in a standard class to talk about it. Finally, the footage which focuses directly on Emeterio Pantale�n, the "last Zapatista," is eye-opening, original, educational, and undoubtedly worth watching.

Andrew Sackett

~ End ~ Video Review of The Last Zapatista Comments | JMMH Contents |