Thom O'Connor's large, luscious prints dominate the three one-person shows

at the University Art Museum.

They are richly visual, highly controlled works

from a master printmaker, which is enough to make a show worth noting. They

also serve as a sendoff for the artist, who is retiring after 37 years of

teaching in University at Albany's

Art Department.

To accompany O'Connor, and as part of a semester-long examination of Irish

culture on campus, there are large black and-white photographs by

Steve Pyke,

and a small show of mildly erotic works by Richard Callner.

Certainly, a retrospective of O'Connor's work could have been in order. I

know I'd appreciate seeing the whole range of his output, which is

considerable. The show includes only recent works, but it is still a

wonderful way of celebrating an active artist with a lot of energy and ideas.

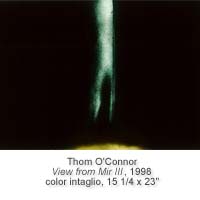

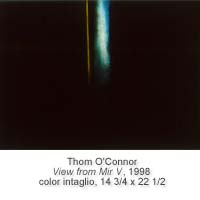

There are several different but related bodies of O'Connor's prints:

small- to medium-size dark bluish/black intaglio or polymer gravure

impressions, large black relief prints with sharp edges of white cutting

through the ink, and large orange intaglios and monotypes with a soft,

blurred sense of motion and light.

In the heavy relief prints called "Night Signals," the impressionism is

clarified and even more abstract, with a few hard lines

intruding in the pure blackness like blades of grass. "A Day on Mars" is

perhaps less like blurred light than blurred motion, as orange

waves swirl over a pane of ground glass.

Whether cast in strong orange-red pigments or kept to a basic inky black on

white, the effect is always a kind of modernized impressionism, romanticized

scenes of Monet. Yet, it is suggestive and attractive in the same broad

manner.

For any viewer seeing all 52 works at once, the works may appear too similar.

Even moving from the orange abstractions to the dark blue ones, or to the

harder black ones, the works are dealing with parallel issues in a comparable,

optical manner. But this show may be unfair to the artist, because you might

typically find them one at a time in a museum or a living room. Perhaps the

advantage to this abundance is their insight into how an artist works,

playing with small nuances that are ultimately part of the success of each

piece, singly or en masse.

When works are as completely abstract and without expressive marks or effects

as these are, the effect can too often be purely formal and decorative.

There is little to think about, and frankly little to feel, in such works.

O'Connor's prints survive because they have unusual visual sensitivity, show

extraordinary craft. There is an undercurrent of drama that suggests, without

delineation, a very human dimension to the works.

Rising above the decorative is difficult and

rare, and O'Connor has made objects of sincere beauty.

There are a few more, rather small O'Connor prints near the base of the

stairs, and these are a good counterpoint to the broad washes of texture seen

elsewhere. Called "Spaces," they have a surprising amount of information,

looking vaguely like black-and-white photographs. Each maintains

a soft-focus sense of light, but the rectangles and diagonals solidify to

form spaces, all refined, as usual, by a sense of falling light.

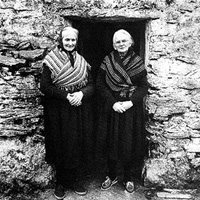

Up the stairs, Steve Pyke's large, square, black-and-white photographs are by

contrast completely sharp and resolved, showing a few people and places in

Ireland. They are so classically serious and gritty that they could have been

taken in another era, such as

Bill Brandt's 1940s. Actually, they are fairly recent photographs, which

appeared first in the photo-novel, "I Could Read the Sky," and they evoke a

timelessness that is perhaps only a myth. Knowing anything about the images

is nearly impossible, as the artist

requested there be no captions or dates, and the original book was unavailable.

In particular, you notice the portraits of rugged people in country places,

taken with poignancy and nostalgia. Is Pyke aggrandizing, or could it be that

these people may in fact, be living close to the land and close to God,

strong, simple, and (to some of us) leading enviable lives?

Whatever the case, there is little revealed except the broadest stereotypes.

We are given only faces, sometimes inexplicably interesting, or details in

the features, but little else. Likewise, the handful of landscapes manage to

evoke the countryside in an all-too-familiar way. A couple landscapes have an

unusual atmospheric effect. There is one portrait of a girl and two women,

which is especially striking. Otherwise this show is just nice enough to last

you while you look at it, not a minute more.

Richard Callner's small group of water colors are studies for illustrating

"Four Love Poems," by John Montague. Callner's trademark landscapes, with

their striped and curved valleys and hills, serve as the basis for giant,

headless female figures that are draped and splayed like corpses over

the horizon. Corpses are certainly not the intention, but these akimbo

figures are one man's image of love: a woman who is, above all else,

accessible.

Two of the four poems reinforce this sentiment, revealing Montague's very

male focus on the crude physicality and terminology of sex. The other two

poems go much further, and though less sensational, are delicately perceptive

and beautiful.

By William Jaeger

Special to the Times Union

Though distinguishable from each other, each group gives a similar impression

of light falling into a room, or of looking into a landscape through a fogged

lens. Everything is left underlined. In the color intaglios called "A Walk

by the Sea," it is as if we are seeing through a layer of thin fabric,

with patches of light hovering within vague dark recesses.

![]()

![]()