An exhibit at the University at Albany Art Museum shows

how artists display their feelings of lossBy Paul Grondahl

Staff Writer, Times Union

Reprinted with permission of the Times Union.

©1997 Times Union, Albany, NY

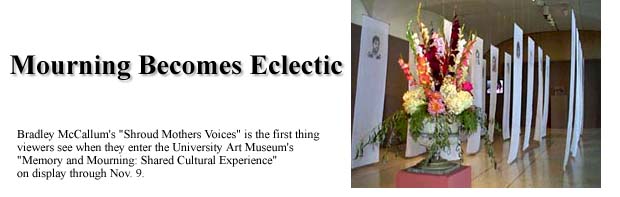

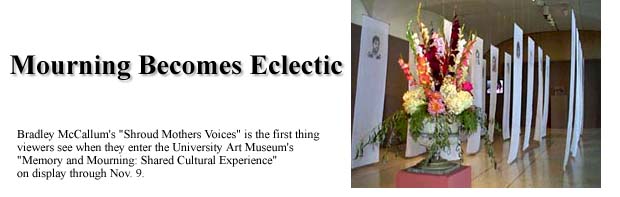

Before you get out of the foyer of the University at Albany Art Museum and into the main gallery, death hits you. Twenty-five sheer white silk banners hang like shrouds from the ceiling, each with a ghostly black-and-white photographic image of a woman staring straight at the viewer. Each is a mother and each lost a son, shot to death with a handgun in New Haven, Conn.Fannet Washington, mother. Curtis Washington, age 17. Died May 15, 1991 . . . Zdravka Crnkovic, mother. Elvis Crnkovic, age 16. Died May 8, l991... Grace Kinlaw, mother. Ernest Kinlaw, age 22. Died Sept. 18, 1991....

"I still lie awake at night grieving for Christian," one mother writes, "and looking forward to my own death."

Artist Bradley McCallum interviewed some of the mothers for a video, assembled here for the University art show "Memory and Mourning: Shared Cultural Experience."

They are a starkly moving memorial to the victims.

"Memory and Mourning: Shared Cultural Experience" is a collection of sculptures, installations, drawings and paintings. Thirty professionally trained contemporary artists, as well as the folk artists whose work is displayed on the second floor of the sprawling exhibit, all struggle with the notion of afterlife and what remains of a person's experience on Earth after death.

In her curator's statement, museum director Marijo Dougherty says the exhibition "allows the visitor to experience ways in which contemporary artists visually manifest their personal feelings of grief, loss and memory."

Walking through the two floors of the museum, the powerful, haunting exhibit unfolds like a multilayered memoir of loss and death. Some viewers are moved to tears and leave in memoriam messages on a "Wall of Recollection" for departed loved ones.

Fresh look

Dougherty, who curated the show with its hundreds of art objects and large installations, began shaping the show and contacting artists more than a year ago. She said the exhibit was meant to be a fresh way of examining cultural diversity on campus and beyond."At first glance, the subject might seem depressing to some, Dougherty said. "But what I'm hearing from visitors over and over is that it's a really uplifting celebration of life and commemoraiton of those who have died.

The recent deaths of Princess Diana and Mother Teresa — and the contrasting shows of public grief that marked their passings — overlays the exhibit. Princess Di and what her death told us about ourselves was a matter of discussion among attendees, whispered behind programs or debated while a viewer clicked on a Life magazine Web site or gazed on her royal visage in a display case filled with pop culture items.

Among the items in the exhibit is a book of condolence for Princess Diana. Visitors can write in the book and it will be sent to the royal family.

Public grieving

"This exhibit comes at an important moment in our society," said Carla Sofka, a UAlbany social welfare professor and a death scholar who wrote an essay for the exhibit catalog and has lent some of her own collection to the exhibit. "With the death of princess Diana, this is the first time in my life that it has become socially acceptable to grieve in public for an extended period of time. I think that's such a healthy thing."For the sculptor Larry Kagan, an associate dean at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where he has taught art for 25 years, those profundities are expressed through a chaotic jumble of twisted wire. It is only when a bright light (truth? divine knowledge? God?) shines through each ungainly assemblage that a shadowy outline of a mesmerizing human face is cast upon the white wall.

The light and shadow interplay of Kagan's wire sculptures implies traces of relatives lost in the Holocaust. Kagan said many of his relatives were killed in Poland and Russia during the Holocaust and he grew up with an absence of family, a void that deeply troubled him and worked itself out in his art.

"Art is about ideas and feelings and some of the strongest feelings come from loss," Kagan said. "Death and loss are about being alive, the whole cycle. This show is about the universality of that experience. It doesn't matter how the person died, the feeling is of a hole in your world when the person is gone."

Across from Kagan's sculptures is an oil on canvas by his longtime friend, Richard Callner, former chairman of the UAlbany art department and founder of its MFA program. Titled "Lazarus (Entombment)" and painted in 1959, the somber swirling and forms address an unspecified loss. Callner writes: "... it is really not comprehensible.... Death must be fought so that its advent does not negate what has died."

What might have been

Some of the art is a soulful cry about what might have been. Native American artist Joanna Osburn-Bigfeather, who earned her MFA in sculpture from UAlbany in 1993, presents a mixed-media installation that is a lamentation of stolen youth.Titled "The Education of Our Indians," her work is a kind of prayer for the scores of young Indian children legally kidnapped from their parents and transferred to government-run boarding schools where they would be "civilized" by a faculty or whites.

"Little children as young as five were stolen from their mothers and there was an emptiness and ongoing mourning and loss among the families back on the reservations," said Osburn-Bigfeather, who is western Cherokee and Mescolero Apache. She grew up in Albuquerque, N.M., and was told of relatives taken away to such boarding schools.

Anchored by four majestic white birch logs (dead trees cut on the UAlbany campus under the artist's direction), her installation is a large enclosure of mesh that resembles a huge butterfly trap.

Empty imagery

Inside, nine wooden crosses are hung. Draped on one cross is a black dress like the ones the Indian girls were forced to wear. On the front of the dress is an apron with a photographic image as faint as an apparition with a group photo of Indian girls housed at the Carlisle Boarding School in Carlisle, Pa., circa 1824. On the back of the dress is a colorful scene of crows in flight. Seven more dresses will be added throughout the exhibit. One wooden cross will be left empty."The emptiness continues," said Osburn-Bigfeather, who runs a gallery of contemporary Native American art in New York City, The American Indian Community House. "I'm interested in a visual rewrite of history. Our history is not in the books."

Climbing the stairs to the second floor is like walking into an early American graveyard as a vast wall space is covered with gravestone rubbings. They, too, are the forgotten ones from "silent cities" of cemeteries, their lives resurrected in the exhibit.

There's a representation of the stone for Rebecca Park. who died in 1803 and is buried in Grafton, Vt. The stone has an image of a tree, with faces of babies as the leaves. Park's 14 children died in infancy, apparently because of a blood disorder in the mother. "See their faces," Park's epitaph read, "like fruit on a vine."

The gravestone rubbings come from the collection of Daniel and Jessie Lie Farber. The Farbers live in Worcester, Mass., and met through a mutual interest in the folk art of ornamental carvings found on early American gravestones.

They married in 1978 and two large collections were joined. He amassed about 19,000 photographs of grave stones; she has more than 300 rubbings. They have traveled to Prague, Turkey, Spain and across the United States just to visit certain cemeteries. Their work is collected at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Mass.

"We were drawn to the folk art in these early American gravestones, which are the earliest sculptures in this country," Jessie Lie Farber said. "I have to admit when Dan and I are working on these stones, we're not weeping and mourning. We are appreciating these great unknown artisans."

The wall of grave rubbings fades into a collection of Victorian mourning jewelry and memorabilia, some of it owned by Sofka, which tells the story of how the American culture has dealt with death across the ages.

Altered states

Across the gallery are altars from several faiths. Alberto Morgan's shrine installation pays homage to the spirits of his African and Cuban religious roots. There are plates of fruit, votive candles, water vases with flower petals, rosaries, bouquets, canes and rattles — all ripe with religious symbolism — along with photos of Princess Di and Mother Teresa."The altar is a form of prayer, of helping the dead person move on to a new space, a spirit space," Morgan said through a Spanish interpreter. Morgan 57, grew up in Havana, Cuba, and arrived in the U.S. 18 years ago during a boatlift. He lives in Union City, NJ., and works as an actor and dancer with Repertory Espanol of New York City.

Facing west on the second floor, beyond a quilt memorializing those who have died from AIDS, there is a wall of recollection and remembrance. Exhibit attendees are encouraged to leave memorial messages. Many tears flowed here reading the handwritten sentiments:

"Dad. I can still hear your laughter after all these years. Your daughter, Ellen."

Or, this one:

"Dear Rob: the days are warm, the trees delightfully dressed in wonderful color. We miss you each and every day. All our love, Mom & Dad. Lucy dog too."

There are children's letters and drawings, a picture of a beloved Husky dog named Jazz, who died in June at the age of 4. Audrey and Dick Lee drove up from Westerlo in Southern Alany County and cried when they read these messages.

I was fluttery in my chest during the whole exhibit, but this part really got to me," Dick Lee said, brushing back a tear. he wrote a haiku for his mother, who died seven years ago. At your graveside / Long last relatives / Resume hugging.

Lee and his wife remembered Lee's brother, who died in a car wreck on Sept. 17, 1977, at the age of 21. "This helps you express your own gried."

She said she is a private person, but was moved for the first time to write a public memorial. "Dad: I miss you every day. You left Jan. 24, 1974. Your daughter."

High above the messages of grief and mourning, a large, colorful funerary kite from Guatemala is caught on the wall like a moth on a door screen, as if hovering in flight, ready to carry off the wight of so much sadness.