The Vasa Capsizes[1]

Managing InnovationThe challenge of managing large-scale projects involving innovative technology has a long history. One particularly illustrative case dates back well over 300 years to the reign of King Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden and the building of the Vasa — “The Tender Ship.”[2] The “Vasa syndrome” has come to refer to a complex set of challenges that ultimately overwhels an organization’s capabilities.[3] |

|

10 August 1628

It was a beautiful summer day and hundreds of Stockholmers had come to the quay at Lodg�rden just below the Royal Castle to wish bon voyage to the Vasa on her maiden voyage. She was a “royal ship,” the biggest, most powerful, expensive and richly ornamented vessel ever built for the Swedish navy, and likely any other navy, at the time. With 64 guns this massive warship was designed to engender pride in the soul of the Swedish people and to strike fear in the hearts of her enemies. And she was decorated for power and glory. According to the prevailing belief of the time, “Nothing can be more impressive, nor more likely to exalt the majesty of the King, than that his ships should have more magnificent ornamentation than has ever before been seen at sea” (Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s pro-navy Minister of Finance).

After vespers services on Sunday August 10, 1628 the Vasa was pulled out of harbor. For the first 200 yards or so she was tugged along shore by her anchors, still in the shelter of a small tier of cliffs to the south. A light wind was blowing from the southwest. As the big ship was pulled seaward, beyond the protection of the last cliff, Captain S�fring Hansson issued his order: “Set the foresail, foretop, maintop and mizzen.” Obediently, the sailors scurried up the great ship’s rig and hoisted four of her ten sails. Just as they did, a slight squall arose from the south southwest, instantly catching the canvases, popping them open, and thrusting the ship ahead.

Watching from the quay the well-wishers witnessed a spectacle that lives in history. According to the Council of the Realm’s letter to the king, the Vasa “... immediately began to heel over hard to the lee side; she righted herself slightly again until she approached Bechholmen, where she heeled right over and water gushed in through the gun ports until she slowly went to the bottom under sail, pennants and all.” In all, she had sailed only some 1400 yards. Now this glorious ship lay 110 feet below the surface of the water. Of the 125 crew, wives and children aboard for this festive occasion, at least fifty perished in the sinking.

It was unprecedented: One of the largest warships ever built had sunk to the bottom of the sea. In her own harbor! Under peaceful conditions! It was more then just a personal tragedy for the family and friends of those who were lost and more than just another military setback for the already weakened Swedish Navy; it was also a major economic catastrophe. In the “King’s Currency” the Vasa cost more than 200,000 Rex Dollars to build, a little over 5% of Sweden’s GNP. One twentieth of the nation’s annual economic product now lay at the bottom of the Stockholm harbor. The Council of the Realm raised questions immediately: Why did it happen? Who was to blame?

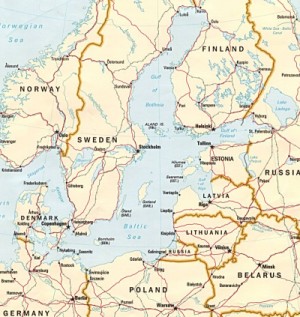

The SituationAt their peak in the middle of the 17th century, the Great Powers included Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and parts of Northern Germany. How did Sweden, with its limited resources, become a Great Power? Centuries earlier, following the Viking period, the Swedish Middle Ages was very turbulent. The throne was not inherited, with the king being elected by members of a council of aristocrats that limited his influence. In 1397, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark formed the Kalmar Union, primarily to counterbalance the increasing political and economic influence of the German Hanseatic League. The countries in the union agreed to elect a common king from Denmark but this later led to a bilateral struggle for power between Sweden and Denmark. During the late Middle Ages there is near political anarchy in Sweden, with a constant struggle for power between a number of families and the Danish King Kristian II ending in “The Bloodbath of Stockholm” in 1520 that enabled Gustav Vasa to become king in 1521. As king, Gustav Vasa started to transform Sweden into an autocratic nation-state with a strong central authority led by an absolute monarch. The most important reform Gustav Vasa made was the reformation of the Church: In order for the king to gain political and economic control over the Church, all Swedes suddenly converted from Catholics to Protestants. This made it possible for the king to replace the Pope as head of the Church as well as use the Church as a propoganda tool on the people. |

|

| In the middle of the 16th century, Sweden, Denmark, Russia, and Poland competed for influence over territories in the Baltic area that had belonged to the now collapsing German Order. The nations surrounding the Baltic Sea were very eager to control the Baltic states because they were central to trade from Russia to Western Europe. The House of Vasa had a cadet, Lutheran Protestantism Royal House in Sweden (1523-1654) and a senior, Catholic branch ruling in Poland (1587-1668). This arrangement led to numerous wars between the two states. John III (b.1537, reigned 1568-1592) married Catherine Jagiello, the sister of Sigismund II of Poland. When Sigismund died without a male heir, John and Catherine’s son was elected king of Lithuania-Poland Commonwealth in 1587 as Sigismund III (1566-1632). On John’s death in 1592, the Polish Vasa died out as Sigismund gained the Swedish throne as King Sigismund I. Sigismund was Catholic, however, which led to his being deposed in 1599. His uncle Charles (Karl) IX succeeded him until his own death in 1611. Karl’s son, King Gustavus (the “Lion of the North”), led Sweden’s subsequent conquest of the northern part of Estonia thereby beginning a very expansive and expensive Swedish foreign policy. |  |

About The King[4]

King Gustavus II Adolphus (Gustav II Adolf in Swedish) was born in 1594. He was considered a natural leader, a spellbinding orator of considerable intellect, and a ferocious fighter. King Gustavus had assumed the throne upon the death of his father King Karl IX in 1611, at the same time inheriting the vicious commercial rivalries surrounding the Baltic Sea. The Swedish aristocracy had strengthened its power position after the death of Karl IX; for instance, Gustavus had to consult the Council of Aristocrats before initiating or ending a war. During his regime, many aristocrats were awarded estates in conquered territories and others were able to buy land originally belonging to the state. The good relations between the king and the aristocracy created a stable political climate.

Poland controlled “Livland” (or Livonia, modern day Latvia) and the coastal areas in the southwest of the Baltic Sea along with important customs revenues from trade with Russia. The Swedish king was, of course, interested in getting his hands on these revenues. The supremacy over Livonia and other important harbor cities in Polish Prussia meant massively increased revenues for the Swedish state. (Customs revenues alone amounted to over 25 percent of the Swedish state income.) The First Polish-Swedish War for Livonia had waged from 1600 until Karl’s death in 1611. Because of the political turbulence in the Baltic area, the English established a new trade route north of Scandinavia to Russia. Sweden’s attempt to sieze control of the northern coastal regions of Scandinavia led to the Kalmar War (1611-13) against Denmark to reduce her navigation tolls; and the Russo-Swedish War (1613-17) to open up her markets. Gustavus eventually reached a peace agreement with Kristian IV, marking the last time Denmark would successfully defend her previous domination of the Baltic. Next, he conducted a successful campaign against the new Russian Tsar, Michael Romanov, made easier by the Russian “Time of Troubles” (1604-13) and the Russo-Polish War (1609-18). Gustavus then turned toward Europe, beginning the Second Polish-Swedish War for Livonia (1617-29).

When the Thirty Years War broke out in 1618, Gustavus hesitated to join as he was more interested in conquering Poland. He was intent on eliminating the threat to the Swedish sect of Lutheran Protestantism which was posed by his cousin — and deadly personal enemy — King Sigismund III, the Catholic who had been deposed from the Swedish throne in 1599 but was still making claims to be reinstated as king. In Gustavus’ eyes, he was the one “who allows himself to be governed by that Devil’s party — the Jesuits.” Gustavus launched his first attack on the Polish stronghold in Livonia in 1621. Within two months the great trading city of Riga — the outlet for about one-third of Poland’s exports — had fallen to his forces.

In 1625 ten Swedish ships, while on patrol in the Bay of Riga, ran aground and were wrecked during an unexpectedly violent storm. This prompted Gustavus, who was still fighting in Poland at the time, to order the Vasa and other ships built and to request their prompt delivery. In 1926, Gustavus’s armies routed the famous Polish cavalry and secured the province of Wallhof. Gustavus now prepared for an assault on Poland’s Prussian possessions to the south. The following year, during a confrontation with the Polish fleet, the Swedish flagship Tigern was captured. The crew of her sister ship Solen then blew up their own ship in order to avoid losing it to the enemy as well. As a result of these devastating losses the king, while still in Poland, sent even more fervent messages home demanding replacement ships. He ordered four ships to be built in the Stockholm shipyard: two large (one would become the Vasa) and two smaller vessels.

Gustavus’ View of the Navy

Wars conducted in another land require supply lines and military protection. Between Sweden and the Continent lies the formidable Baltic Sea. A powerful fleet was therefore indispensable to the king and his army. “Second to God,” the deeply religious Gustavus once proclaimed, “the welfare of the Kingdom depends on its Navy.” A strong navy was necessary for accomplishing four crucial missions:

- To protect Sweden against attacks from abroad.

- To carry troops and materiel to theaters of war on the other side of the Baltic.

- To provide revenue for Sweden by blocking Danzig and other ports in Poland, and by levying customs duties on the many cargo ships that used these ports.

- To blockade hostile ports, preventing the enemy’s fleet from leaving on penalty of being conquered, bombarded, or sunk.

A Chronicle of Events

The key events leading up to the capsizing of the Vasa begin when a new naval shipyard was opened in Stockholm at least five years before the king’s order.

1620

Antonius Monier leased the naval shipyard in Stockholm and employed the Dutch Master Shipwright Henrik Hybertson. Hybertson is an experienced shipbuilder of the highly respected “Dutch School” of shipbuilding. Eventually he will be responsible for designing and building the Vasa. According to the methods used during this era most of the design requirements were kept in the head of the Master and executed according to his “School” of thought and his experience. No scientific theory of vessel design or stability was available. The shipwright made no mathematical calculations, for example, to determine such important factors as a ship’s center of gravity, its center of displacement volume, its form stability, or its weight stability. There were no schematics or engineering drawings. Instead, a ship’s “reckoning” was used. It contained figures on the ship’s main dimensions, its principal construction details, and other related facts. Everything else was up to the craftsmanship, professional skill, and experience of the master shipbuilder.

1621

Monier and Hybertson contract to produce three ships during the next five years. Admiral Klas Fleming is appointed by the king to oversee the contract. Pursuant to this contract the Maria is to be delivered in 1622, the Gustavus in 1624 and the Mercurius early in 1625. Since previously it took two to three years to complete a single ship, this contract called for a speeded-up overall rate of production.

1622

In February Monier and Hybertson contracted to build an additional ship the Tre Kroner. Similar to Mercuris it will have 30 or 32 guns and a 108 foot keel[5]. This means that the shipyard now has four ships under contract. (The Tre Kroner was launched in the autumn of 1625 and delivered to the Navy in 1626.)

1624

At the behest of the king, the Admiralty issues shipbuilding plans as follows:

- 1626: one large ship, with a 136 foot keel and 34 feet wide bottom,

- 1627: one smaller ship, probably with a 108 foot keel,

- 1628: one large ship also 136 feet long and 34 feet wide, and

- 1629: one smaller ship, also probably with a 108 foot keel.

1625

The pace of activity picks up during 1625. On January 16 Hybertson and his brother Arendt de Groot, a businessman with good contacts with suppliers in both Sweden and Holland, signed a contract to build and deliver the four ships called for in the Admiralty’s plans. The contract was not to become effective until January 1626 when Monier’s original contract would expire. The Tre Kroner, ordered in 1622, was still not completed; consequently, the contract obligated Hybertson to “complete and fulfill according to the wording and content of the previous contract whatever is still missing upon the ships and vessels lying at the shipyard.” Thus, the Tre Kroner was to be completed before the Vasa was begun, the Vasa being a larger ship and the first of the new ships ordered.

The contract identified only the length and width of the ships. There were, as was the practice, no full written specifications or drawings. Thus, the master shipwright was responsible for determining the form and proportions of the Vasa’s hull,[6] calculating its main dimensions, and indicating how the ship would be manufactured. After the hull was launched, Hybertson’s primary design and building responsibilities were completed.[7] He then became a manager overseeing the manufacture and mounting of the sculptures that adorned the ship. Not necessarily a trivial job — this magnificent ship featured over 500 sculptures of lions, angels, devils, warriors, musicians, emperors, and gods and more than 200 carved ornaments. It was designed to impress not only with her firepower, but also with her abundant sculptures. The shipwright was also responsible for fixing the gun carriages, checking out the rigging, and preparing for future maintenance work. From this time forward, however, Hybertson had little, if any, influence on the ship’s naval architecture, equipment, or its armaments.

The work load in the shipyard was increased considerably in mid-February when a contract was signed to complete work on the �pplet, a ship originally begun in the early 1620’s that required strengthening of its keel, stem, stern, and related parts. During the spring, in accordance with his contract, Hybertson notified Admiral Fleming, who was handling the business for the king, that he had ordered timber to be cut for one large 136 foot ship and two smaller 108 foot ships. (It is possible that the contract to finish the �pplet resulted in the postponement of the second large ship.) The large ship referred to is likely the Vasa and its original keel, which was 136 feet long, was probably laid down at this time.

In September the Navy lost ten ships in the Bay of Riga. The king is with his army in Poland at the time. He immediately demands that the two smaller ships be delivered sooner than called for in the original contract. On October 3, Admiral Fleming forwards Hybertson’s specifications for the Tre Kroner to the king. They specify a keel with a length of 108 feet. Plans call for launching the ship by the end of the month.

Feeling the economic pressures of his war efforts, on November 3 the king writes to the Council of the State ordering the Council and the Nobility to contribute money for the construction of two new ships to be built in Hybertson’s yard. The next day the king answers Admiral Fleming’s communiqu� and requests that Hybertson be notified that he [the king] has made changes. The new specification now calls for building two smaller ships rather than beginning construction on the larger one. Acknowledging receipt of the earlier specifications the king says that he has “somewhat altered it ... desiring that you [Fleming] with Master Henrik agree that he construct the two smaller ships according to our enclosed specification,” and gives him a width in the bottom of 24 feet and a keel length of 120 feet, “about which nothing is mentioned in the specification sent here by you.” This creates a difficult problem for Hybertson. He cannot build the 120 foot ship requested — a size between the Tre Kroner (108 ft.) and the Vasa (136 ft.) — with timber already cut for the ships under construction without, as he put it, “detriment to self.”

On November 30 three sets of specifications are entered in the National Registry: First, the king’s own specifications for the ships to be built. Second, Hybertson’s specification for the ship that is timbered in the shipyard in Stockholm. (These two specifications do not agree on important dimensions concerning keel length and bottom width.) And, third, specification for a ship to be built by another shipbuilder.

1626

Hybertson officially notifies Admiral Fleming on January 2 that the timber he has cut does not match the king’s new specifications. This applies to both the smaller and large ships.[8] On February 22 the king replies to Hybertson’s letter. He orders him to build the ships according to his [the king’s] specifications, adding that if he is not willing to build two ships according to these specifications, he should instead build the 136 foot ship contracted for. Hybertson reports on March 20 that a ship is under construction and that its keel length is 120 feet. Summoned to the Chancery on the next day and notified of the king’s wishes, he promises to do whatever he can to satisfy the king’s demands. (Three hundred years later it is discovered that the Vasa’s keel was built using four keel timbers united by three scarf joints.[9] Beginning at the stern the first three keel timbers measure about 111 feet long. Including the fourth timber the keel reaches 136 feet in length.)

1627

In the spring Hybertson dies from an extended illness. His assistant, Hein Jacobsson, who has very little managerial experience, takes over with the aid of his young assistant Johan Isbrandsson. Hybertson had been sick for about two years and communications have suffered as a result. Jacobsson has no detailed records or descriptions from which to work. Also in the spring the plans for the Vasa’s armament are filed with the Ordnance Master: 36 24-pound canons, 24 12-pound canons, 8 48-pound mortars, and ten small guns for the fighting troops. The total weight is in excess of 70 tons. This is too much armament to be accommodated on one enclosed deck and one open deck. Consequently, the Vasa had to be altered to have two enclosed battery decks, making it very likely the first ship ever built in Sweden with two gun decks. Late in the year the hull of the Vasa is launched. Work is now begun on fitting the ship out.

1628

In January the king visits the shipyard and inspects the Vasa. He then returns to Europe to continue fighting. The armament plan filed the prior spring is revised. Subsequently, the Shipyard Requirement List shows another revision. This list was then revised two more times. On her maiden voyage the Vasa had 64 guns on board. Her main firepower was 48 24-pound canons distributed evenly between the lower and upper gun decks.[10] The table below summarizes these changes:

Armament Type |

1627 Plan |

1628 Plan |

Revised List 1 |

Revised List 2 |

Revised List 3 |

Actual when Capsized |

Canon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

24-lbs |

36 |

30 |

60 |

54 |

58 |

48 |

12-lbs |

24 |

30 |

- |

12 |

8 |

- |

6-lbs |

- |

8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3-lbs |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

1-lbs |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

Mortars |

|

|

|

|

|

|

48-lbs |

8 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

6 |

24-lbs |

- |

2 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

Small Guns |

10 |

? |

? |

? |

? |

Few |

As the war heats up in Europe, the king orders that both the Vasa and another ship be ready for battle by July 25, 1628, “... if not, those responsible would be subject to His Majesty’s disgrace.” In late summer Admiral Fleming conducted a stability test of the Vasa. Neither of the two shipbuilders, Jacobsson or Johan Isbrandsson, was present. For the test thirty men are required to run abreast from one side of the ship to the other. After the third crossing they were stopped. The Vasa was heaving and heeling so violently that there was a considerable risk that she would capsize. Boatswain Matsson,[11] who witnessed the test, told the Admiral that “the ship was narrow at the bottom and lacked enough belly.” The Admiral’s response was “the shipbuilder has built ships before.” He should not be worried. Later, Matsson could only sigh with hope: “God grant that the ship will stand upright on her keel.” Following the test the Admiral took no further action. Even the shipbuilders were not notified. Fleming, however, reportedly uttered a wish: he hoped “that His Royal Majesty had been at home” to witness the test.

While the stability test was being conducted, the armament was still in the process of being produced and the artists were still working feverishly to complete the decorations. Consequently, it is unlikely that much, if any, of the armament or the decorations were on board at the time of the test. On July 31 the king orders that the guns be taken aboard and that the marines be fully outfitted and moved into their quarters so that the Vasa can rendezvous with his fleet in the Baltic. On August 10 the Vasa sank.

Inquiries

The king was in Prussia on August 24 when news of the disaster reached him. “Imprudence and negligence” must have been the cause, he wrote back angrily to the Council of the Realm, demanding in no uncertain terms that the guilty parties be punished. Another inquiry, however, was already under way. Captain S�fring Hansson had been arrested and put in prison immediately after the disaster. The next day a preliminary hearing was begun. Based on the records that have been preserved, it appears to have gone something like the following:

“Had you failed to secure the guns properly?” Captain Hansson was asked on August 11. (The canon had been fitted with wheels. Consequently, some thought that the windward guns might have rolled over to the lee[12] as the ship started to heel, shifting the ship’s weight and contributing to her instability.)

“You can cut me in a thousand pieces if all the guns were not secured,” he answered. (Three centuries later his claim was proven true.)

“Were you intoxicated? Was your crew?”

“And before God Almighty I swear that no one on board was intoxicated,” was the reply. (Also likely to be true since before boarding most had just come from religious services held that morning.)

“Was the ship stable?”

“Ballast was there as much as there was room for, and 100 lasts more than Admiral Fleming wanted, and the ship was [still] so tender that she could not carry her masts. ... It was just a small gust of wind, a mere breeze, that overturned the ship,” Captain Hansson continued. “The ship was too unsteady, although all the ballast was on board.”[13]

Next, Boatswain Matsson gave his testimony describing Admiral Fleming’s stability test with thirty men. Other questions were raised. Was the ship incompetently handled or maneuvered? Did she carry too large or too many sails? Was she overloaded? Was there something wrong in her design or construction? No incriminating answers were forthcoming.

Attention was then turned to the surviving shipbuilders, Jakobsson and Isbrandsson, and their business partner de Groot. The judge asks Jakobsson, “Why was the superstructure heavier than the lower part?” Several others had already testified that the Vasa was “heavier above than below.”

Jakobsson answered that he built the Vasa according to the “instructions, which had been given to him by Master Henrik, and on His Majesty’s orders.” The ship conformed to all the measurements submitted to the king before the work began, he asserted, and His Majesty had approved these measurements. The number of guns on board was also as specified in the contract. De Groot mentions that the ship was built in accordance with the Dutch prototype, also approved by the king.

“Whose fault is it, then?” the court asked.

“Only God knows,” de Groot replied. And, with that the first inquiry was finished.

On September 5, a Naval Court of Inquiry, chaired by the king’s half brother Admiral Karl Karlson Gyllenhielm, began in response to Gustavus’ demand to find the guilty parties. The court was comprised of 17 persons, six of whom were members of the Council of the Realm and present at the previous inquiry. No conclusive result as to the cause of the disaster was reached by this second inquiry either. No one was ever found guilty. No one was punished. The affair ended with no one knowing why it happened or who was to blame. Although blame was not firmly assigned, construction of Swedish warships subsequently came under more direct control of the Navy. After the Vasa, many successful war ships were built with two, three, and even four gundecks. The shipbuilders learned from the mistakes with the Vasa and improved their designs.

Requiem for the King[14]

History treats Gustavus II kindly. When he assumed the throne, Sweden was a small, impoverished country, humbled and at the mercy of the Danes. In 1630, he entered the Thirty Years War as the German Emperor and his forces in Northern Germany threatened Swedish interests in the Baltic area. This was the beginning of the so-called Swedish Period (1630–35). Finland, Ingermannland, Estonia, and Livonia all belonged to the kingdom of Gustavus, and Courland was under Swedish influence. The conquest of Prussia and Pomerania would have made the Baltic nearly a Swedish sea. Gustavus concluded a subsidy treaty with France (Richelieu), drove the imperial forces from Pomerania, and captured Frankfurt-on-the-Oder. At the time he was slain at the Battle of L�tzen in 1632 (which eventually ended in a Swedish victory), Sweden had become the strongest force in Northern and Central Europe. His success was attributed to his personal magnetism, his demand for stern discipline — people seldom crossed the king — and a creative military mind. His innovations included building a national standing army, deploying small and mobile units, developing strategies based on superior firearm power, and integrating land with naval warfare. He was succeeded by his daughter Queen Christina (Kristina), who abdicated in 1654 and became a Catholic. The throne of Sweden passed to the House of Palatinate (Pfalz-Zweibr�cken), a cadet branch of the Wittelsbachs. In the peace of Westfalia in 1648, Sweden was established as a Great Power. These wars were very costly for Sweden, however, as only a small portion of the Swedish troops were Swedes or Finns. The use of mercenaries was extensive and expensive, in fact so devastating to the state finances that eventually the Swedish army was completely reorganized with soldiers recruited domestically and leading to the system of compulsory military service of today.

Fast Forward to 1961

“An old ship has been found off Beckholmen in the middle of Stockholm. It is probably the warship Vasa, which sank on her maiden voyage in 1628. For five years, a private person [Anders Franz�n, a specialist on wrecked naval vessels] has been engaged in a search for the ship.” This item, published in a Swedish newspaper over three hundred years later, announced again to the world the fate of the Vasa. The raising of the Vasa from the harbor began on April 24, 1961. Due to the brackish water of the Baltic it was remarkably well preserved. It can be seen today at the Vasa Museum in Stockholm located not far from where it was originally built and where it capsized. The raising prompted a search once more for why it capsized and who was to blame.

Discussion Questions

- Why did the Vasa capsize? What contributing role did the various parties play? Who was responsible?

- In what ways is the Vasa story like other large-scale systems failures you are familiar with? Does the building of the Vasa differ from the Bhopal, Chernobyl, or Challenger disasters?

- Is fear — whether of personal embarrassment or of the “wrath of the boss” — the root cause of most project management failures?

- Some organizations have had large-scale systems successes. How have they avoided the pitfalls encountered in building the Vasa?

- Was this truly a disaster? What lessons can be learned from this case and similar disasters, particularly regarding the importance of such “human factors” as courage, truthfulness, and open communication?

Footnotes

[1] This case was originally prepared by Professor Richard O. Mason of Southern Methodist University from public sources to be used for purposes of classroom discussion. Also see Lars Bruzelius, Sailing Ships: “Wasa” (1627) and Dottie E. Mayol, The Swedish Ship Vasa’s Revival.

[2] So dubbed by Professor Arthur M. Squires in his book The Tender Ship: Governmental Management of Technological Change, Boston: Birh�user, 1986.

[3] Eric H. Kessler, Paul E. Bierly III, and Shanthi Gopalakrishnan, “Vasa Syndrome: Insights from a 17th century new-product disaster,” Academy of Management Executive, 2001, 15(3): 80-91.

[4] Based on The Sweden Information Smorgasbord.

[5] The keel is the principal structural member of a ship, running lengthwise along the center line from bow to stern, to which the frames are attached.

[6] The hull is the frame or body of a ship, exclusive of masts, sails, or superstructure.

[7] A 1670 Swedish shipbuilding manual summarizes the Dutch method. First the keel was laid. Then the bottom planking was added, being held together by wooden chocks nailed on. Following this the floor timbers were laid and the ribs built up around them. The skin shell was added, strake by strake, until the hull was high enough to float. Then the hull was usually launched bow first and work continued while the ship floated in the water. English and French shipwrights used a different method.

[8] Timber, of course, is a crucial resource for shipbuilding. For example, over one thousand oak trees were used in building the Vasa. In order to obtain the correct dimensions, the trees had to be located and specially felled for each part of every ship. Because the Navy’s requirements were substantial, oak trees and other trees used in ship construction were protected by law.

[9] A scarf joint is a joint made by cutting or notching the ends of two pieces correspondingly and strapping or bolting them together.

[10] Records show that the final armament count was 48 24-pound canons, 8 3-pound canons, 2 1-pound canons, 1 16-pound siege gun, 2 62-pound siege guns, and 3 35-pound siege guns for a total of 64 guns. Each 24-pound canon weighed about a ton and one-half and had a gun-crew of seven.

[11] A boatswain is a warrant officer or petty officer who is in charge of a ship’s rigging, anchors, cables, and deck crew.

[12] In nautical terms “the lee” is the side away from the direction from which the wind blows or the side sheltered from the wind.

[13] Ballasting was done by “feeling” at the time, usually by simply filling the available space. Recent studies show, however, that there was not enough ballast aboard, ballast being a heavy material — in this case stone — that is placed in the hold of a ship to enhance its stability. Moreover, if more ballast had been added, as boatswain Matsson wanted but Admiral Fleming refused to allow, water would have come pouring in the gunports on the lower gundeck.

[14] The Sweden Information Smorgasbord, ibid.

Revised by Paul Miesing on May 09, 2004.