FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

Clockwise

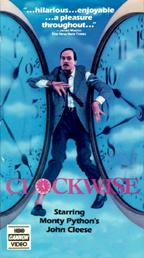

Clockwise

(British, 1986, 96 minutes, color, 16mm)

Directed by Christopher Morahan

Cast:

John Cleese . . . . . . . . . . Brian Stimpson

Penny Leatherbarrow . . . . . . . . . . Woman Teacher

Howard Lloyd-Lewis . . . . . . . . . .Ted

Jonathan Bowater . . . . . . . . . . Clint

Alison Steadman . . . . . . . . . . Gwenda Stimpson

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

British film comedy has always loved to burst the bubble of puntiliousness. In KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS, Alec Guinness made the doomed members of the aristocratic D’Ascoyne clan exponents of mindless orderliness. When each one of them is dispatched by a brooding nephew in this dark comedy, we can’t help smirking in delight. TIGHT LITTLE ISLAND found the Scots bugging their supercilious English "occupiers" during World War II, as the English drove themselves to distraction looking for a hidden cache of whiskey from a torpedoed freighter. And again, we sided with the forces of anarchy. Peter Sellers and his Goon Show mob, the "Beyond the Fringe" group, and penultimately, Monty Python’s Flying Circus took aim at what has, after all, sometimes been thought of as the British national ratio—the passion to enforce silly rules rises with the absurdity of the rules themselves. Countless Python skits, including the "Dead Parrot" bit, "Self Defense with a Pointed Stick," and "Having an Argument," and of course, "The Ministry of Silly Walks" are built on the sheer joy of dismantling British self-importance.

The Python alumnus who personifies British stuffiness in its most suicidal mode is John Cleese. After his Python triumph, he created a virtual poster child for stiff upper lipped lunacy in the deranged hotel keeper Basil Fawlty, whose BBC television hostelry, Fawlty Towers, always runs just fine until Basil feels a need to exert his dubious management skills, at which point guests flee, employees quail, and fire extinguishers empty. In a series of industrial films, Cleese used his stiff-necked comic persona to advise the service industries on the need for flexibility and listening skills in dealing with customers, attributes of social intelligence the classic Cleese character hasn’t got a jot of. The idea behind this group of films was later crystallized as the sublime phony instructional film, "How to Irritate People." Cleese’s supporting roles in feature films have frequently stolen the show at virtual comic gunpoint, such as in A FISH CALLED WANDA, directed by an old English film comedy hand, Charles Crichton. Until CLOCKWISE though, Cleese had been searching for a leading role to fit the outsized loon’s ego of his trademark character.

In Christopher Morahan’s film, Cleese has found his lunatic muse. Cleese plays "Brian Stimpson," a petit-fascist headmaster dedicated to punctuality and appearance to the exclusion of all else, especially including meaningful learning. "The first step in knowing who we are is knowing when we are and where we are!" he pontificates, as if anyone besides himself knows what he means. No matter, because Brian Stimpson is one of the most deeply self-satisfied characters in all of film history. He is Big Brother with a stopwatch and a bullhorn, every kid’s nightmare of a school administrator. His toothbrush mustache cues us as to who his real model might be, but unlike Der Fuehrer, Stimpson poses no threat to world order, merely to the benighted pupils he treats like medieval peasantry in his feudal realm. There is no appeal from his ridiculous dicta, and we see students lined up for ritual humiliation every morning at 9:20. Precisely, always precisely, at 9:20.

Stimpson has been chosen (by God, to hear him tell it) to lead a conference of headmasters at Norwich. The film’s premise is the apparently innocuous one of getting Stimpson to Norwich on time. But Brian Stimpson makes a simple mistake, and a chain of delightfully unfortunate circumstances occurs which make getting to Norwich this film’s equivalent of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow. The inanimate world seems to rise up in concert against him. By the time Stimpson has encountered vengeful pay phones, sinister train schedules, and a police car with a soul, we begin (horrors!) to sympathize with him. After all, even Attila the Hun must have had to tangle with missing collar buttons and broken shoelaces.

Time’s winged chariot seems to be leaving Stimpson in the dust, as the clock ticks off the minutes before his valedictory speech to his fellow headmasters. All seems lost, when a rescuer appears from an unlikely corner. But is it rescue—or something far worse? Monks, cops, headmasters, batty old ladies, rogue students, all join in Brian Stimpson’s richly deserved torture. Like Buster Keaton in SEVEN CHANCES, John Cleese makes the proceedings all the more delicious by refusing to surrender his battered dignity, although, unlike Buster, he takes it on the chin with something less than a deadpan style. Instead, Cleese’s teeth are so tightly clenched in anger that we fear he will surely crack his upper plate, and we settle back to enjoy one more stone in the road, one more pebble in the shoe, one more catastrophe, in the manic existence of a man we all know too well, from work, from school, from life.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.