|

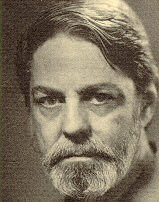

Shelby Foote, fiction and nonfiction writer, best known for his three volume historical work The Civil War: A Narrative (1958, 1963, 1974), is also highly regarded for his novels and short stories concerning the heritage of the American South. His novels include Follow Me Down (1950, 1978), Love in a Dry Season (1951, 1992), Shiloh (1952, 1976), and September, September (1978). Foote provided commentary for Ken Burns' PBS television series, The Civil War.

Shelby Foote visited the New York State Writers Institute on March 20, 1997.

Twenty years ago, in 1954, novelist Shelby Foote began this monumental work with these words: "It was a Monday in Washington, January 21; Jefferson Davis rose from his seat in the Senate . . ."

In the third-and last-volume of this vivid history, he brings to a close the story of four years of turmoil and strife which altered American life forever. Here, told in vivid narrative and as seen from both sides, are those climatic struggles, great and small, on and off the field of battle, which finally decided the fate of this nation.

1

1

"Red River to Appomattox" opens with the beginning of the two final, major confrontations of the war: Grant against Lee in Virginia, and Sherman pressing Johnston in North Georgia. While the Virginia-Georgia fighting is in progress, Kearsarge sinks the Alabama and Forrest gains new laurels at Brice's Crossroads.

With Grant and Lee deadlocked at Petersburg, Sherman takes Atlanta--assuring Lincoln's reelection, together with the certainty that the war will be fought (not negotiated) to a finish. These events are followed by Hood's bold northward strike through middle Tennessee while Sherman sets out on his march to the sea, to be opposed at its end by the ghost of the Army of Tennessee. Hood is wrecked by Thomas in front of Nashville the last big battle--and Savannah falls to Sherman, who presents it to Lincoln as a Christmas gift.

Meantime, Early has threatened Washington, Price has toured Missouri, Farragut has damned the torpedoes in Mobile Bay, Forrest has raided Memphis, and Cushing has singlehandedly sunk the Albemarle. And Sherman heads north through the Carolinas, burning Columbia en route, while Sheridan rips the entrails out of the Shenandoah Valley.

Lincoln's second inaugural sets the seal on these hostilities, invoking "charity for all" on the Eve of Five Forks and the Grant-Lee race for Appomattox. Here is the dust and stench of war, a sort of Twilight of the Gods, with occasional lurid flare-ups, mass desertions, and the queasiness that accompanies the risk of being the last man to die.

Then, penultimately, Lee at Appomattox, the one really shining figure in this last act. Davis's flight south from fallen Richmond overlaps Lincoln's death from Booth's derringer, and his capture at Irwinville comes amid the surrender of the last Confederate armies, east and west of the Mississippi River. The epilogue is Lincoln in his grave; and Davis in his posthumous existence, "Lucifer in Starlight."

So ends a unique achievement-already recognized as one of the finest histories ever fashioned by an American--a narrative of over a million and a half words which recreates on a vast and brilliant canvas the events and personalities of an American epic: The Civil War.

Although he now makes his home in Memphis, Tennessee, SHELBY FOOTE comes from a long line of Mississippians. He was born in Greenville, Mississippi, and attended school there until he entered the University of North Carolina. During World War II he served in the European theater as a captain of field artillery. In the period since the war, he has written five novels: Tournament, Follow Me Down, Love in a Dry Season, Shiloh and Jordan County. He has been awarded three Guggenheim fellowships.

"A stunning book full of color, life, character and a new atmosphere of the Civil War, and at the same time a narrative of unflagging power. Eloquent proof that an historian should be a writer above all else." -Burke Davis

"Here, for a certainty, is one of the great historical narratives of our century, a unique and brilliant achievement, one that must be firmly placed in the ranks of the masters... a stirring and stupendous synthesis of history." - Van Allen Bradley, Chicago Daily News

"A grand, sweeping narrative... will continue to be read and remembered as a classic of its kind." - Richard N. Current, N.Y. Herald Tribune

"This, then is narrative history-a kind of history that goes back to an older literary tradition... The writing is superb . . .one of the historical and literary achievements of our time."- T. Harry Williams, Book World

"The lucidity of the battle narratives, the vigor of the prose, the strong feeling for the men from generals to privates who did the fighting, are all controlled by a constant sense of how it happened and what it was all about. Foote has the novelist's feeling for character and situation, without losing the historian's scrupulous regard for recorded fact. The Civil War is likely to stand unequalled."- Walter Millis