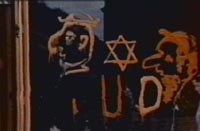

| Survivors explain their perception

of Hitler's early threats.

28.8 | 56 | Cable/T1

|

|

Witness: Voices from the Holocaust.. Video. 86 minutes. Joshua M. Greene and Shiva Kumar, producers. Stories to Remember, in association with the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust

Testimonies, Yale University. 1999. For more information on the video and its companion book, Witness: Voices from the Holocaust, Greene, Joshua M. & Shiva Kumar, Editors, Free Press, 288 pp., go to: http://www.strmedia.com/witness/index.html.

The outpouring of survivors' testimonies

in the past generation has enriched the study of the Holocaust immensely.

When participants are able to tell their own stories they can animate

history as nothing else can. That so many articulate people survived

to write memoirs or to describe their experiences to students, filmmakers,

and archivists is one reason that the subject has captured the public

imagination in the United States and much of Europe. The scholarly implications

of the popularity of these testimonies are increasingly clear, however.

Not only are fakes occasionally unmasked, such as Binjamin Wilkomirski's

Fragments: Memoirs of a Wartime Childhood, which won the 1996

National Jewish Book Award for Autobiography and Memoir. But these testimonies

may also come to dominate the field, with confused or conflicting accounts

opening the way for Holocaust deniers to cast doubt on their validity.

|

Frank S. describes the teaching

of "Racial Science" in 1930's Germany.

28.8

|

56 |

Cable/T1 |

|

Filmmakers must address these concerns when

using survivors' accounts. Usually, they have been incorporated into a

traditional documentary format, along with voice narration, archival and

contemporary footage, and interviews with experts on the subject. The

Fatal Attraction of Adolf Hitler, the 1989 BBC documentary (reviewed

in The Journal for MultiMedia History, Volume 2, 1999), is one

widely praised example of this genre, covering a broad sweep of history.

Most films take a more limited subject, such as the "Night of Broken Glass"

or partisan warfare in Vilna, and use testimony—usually in translation—as

one element in the story they are telling.

Joshua Greene and Shiva Kumar have chosen

a bolder approach in Witness: Voices from the Holocaust. Drawing

on the Fortunoff Video Archives at Yale University, which since 1979 has

collected testimonies of some four thousand survivors, they present nineteen

eyewitnesses speaking in English, with no narrator, experts, or translators

standing between them and their audience. The survivors are articulate

and the viewer sees enough of them as they appear from time to time or

their voices are heard while archival film is on the screen to be moved

by their stories. Most of the nineteen are Jewish, but they also include

a former American POW in a German camp, another American who took part

in the liberation of a camp, a former Hitler Youth member, and a priest

who witnessed deportations. The result is a powerful, effective, and award-winning

film, aired nationally by PBS in May, 2000, as well as a companion book

with a foreword by the distinguished scholar Lawrence L. Langer. It, too,

has drawn wide accolades.

|

Father John S., a Czech priest,

describes the "collective crime"

of

indifference and fear of denunciation.

28.8 | 56 | Cable/T1

|

|

Greene and Kumar are television producers with a long string

of credits, chiefly in producing animated and live-action films for children.

In interviews he gave after making Witness, Greene made it clear

that he had not read much about the Holocaust during the four years he

spent on the film and book. He tried instead to let the testimony speak

for itself, to "step away from the control inherent in his craft as a

filmmaker, relinquish the expectations that accompany interviews."[1] Witness

may succeed in these terms and even awaken the interest of schoolchildren

in the subject—which would be no small accomplishment—but it

also raises a number of questions of particular concern to scholars.

Scholars may be irritated by some of the

choices the filmmakers made. Why was an American POW chosen as a "voice

from the Holocaust" but not a Romany or Polish person? Simply because

the Fortunoff Video Archive has his testimony and not theirs? How representative

are the survivors and how accurate are their statements? Is Robert S.,

the former Hitler Youth member, correct in saying that Germans were all

in favor of war at the outset? Is Joseph K. fair in saying that the Polish

Nationalist Party fell under the influence of the Nazis? Were many American

prisoners of war put in places like Mathausen, as Herbert J. was,

rather than in POW camps?

| Robert S., former

Hiter Youth member, asserts that

most germans

were for the war.

28.8 |

56

|

Cable/T1 |

|

Though I cannot ignore these questions, I believe

that the dramatic impact of Witness would have been seriously compromised

by a more conventional approach to the use of testimonies. A narrator

could have answered some questions, framed some issues differently, but

at a price. Scholars who work with survivors often stress how we can enlarge

our understanding of the Holocaust if we encourage them to express themselves

freely and avoid imposing our own categories and questions. Witness

is a beautifully wrought example of the directness and power that can

be achieved when survivors are allowed to tell their own stories.

What child could listen to Frank S. describe his

classroom experience without being moved? A Jewish child in a biology

classroom when "Racial Science" was being taught in 1930s Germany, he

was ridiculed by his teacher for his non-Aryan features. The hatred for

that teacher that has stayed with him for fifty years is palpable. The

terrible deportation journey in crowded cattle cars is handled beautifully,

with interwoven accounts of survivors and of Father John S., a Czech priest,

who watched the train roll by his town and described the "collective crime"

of indifference and fear of denunciation, as no one came to the aid of

their former neighbors.

Hollywood treatments of Nazi concentration camps

do not probe the depths of the human experience the way the testimonies

in Witness do. Emotions are raw and on the surface as people describe

what they went through or subjected others to. There is the testimony

of a survivor still haunted by the knowledge that he sent his little brother

to his death by steering him to the wrong line during the selection process.

Martin S. described how he trained himself to be brutal in order to survive

in Buchenwald. "I didn't care about anyone else." One woman describes

how hunger drove her to steal bread from a fellow prisoner. Herbert J.,

the American POW, describes the brutality of Nazi guards and the cannibalism

of Soviet inmates.

There are no tidy conclusions to Witness.

Martin S. returns to Poland looking for his family and finds only hostility

from his former neighbors. He and Renee H. explain what happened to them

when they made their way to the United States. No one wanted to hear about

their experiences; they chose to remain silent for a generation. Another

survivor ends Witness with a question: "Did we really learn anything?

I don't know."

Notes:

-

Joshua Greene on The Paula Gordon Show, "Survivors: Introduction." Go to:

(http://www.paulagordon.com/shows/greene/. [Return]

Donald Birn

University at Albany, State University

of New York

~ End ~

Video Review of Witness: Voices from the Holocaust

Copyright © 2000, 2001 by The Journal for MultiMedia

History

Comments | JMMH

Contents

|